Edward Carey’s inspiration for his novel, Little, based on the life of Madame Tussaud, came from his brief period working at Madame Tussauds in London. Madame Tussaud, also known as ‘Little’ due to her diminutive stature, was born Anne Marie Grosholtz and took her famous name from her husband, François Joseph Tussaud, whom she married in 1795. Marie, as she is mostly known as in the novel, was trained in the art of wax portraits by her guardian, Doctor Philipe Curtius. Curtius was a Swiss physician who not only taught Marie the art of working wax, but physiology as well. The novel tells its story well and is illustrated throughout by the author with drawings attributed to Marie as part of the narrative.

My own exposure to Madame Tussaud before reading this novel was, like most I suspect, a visit to one of the numerous wax exhibitions around the world that are branded with her name. I’ve been to one in Hollywood as well as one in Sydney at Darling Harbour. It’s worth considering these modern versions for a moment to understand how interesting Marie Grosholtz’s – Madame Tussaud’s – life was beyond the brand name it has become. Both the Hollywood and Sydney versions focussed heavily upon modern celebrities, particularly American politicians, movie and music stars, as well as the characters they portray. In Sydney there was some local flavour added, but the experience was very much the same. The emphasis was on glamour.

Yet there is a tradition that wax works are a place where one encounters the grotesque and horrific. The 1953 film starring Vincent Price as Professor Henry Jarrod, The House of Wax, was the first colour 3d film, which was something I always wondered at. There’s a scene with a man hitting an elasticised ball which zooms in and out at the audience, but apart from that the 3d experience would have been fairly basic. Henry Jarrod turns out to be something of a monster, killing innocents to further his art. Like the traditional house of horrors – portraits of murderers, of bodies and executions – the film associates violence and the macabre with wax figures and the choice of 3d not only accentuates this, but is a fitting aesthetic choice to represent a medium which was always three dimensional.

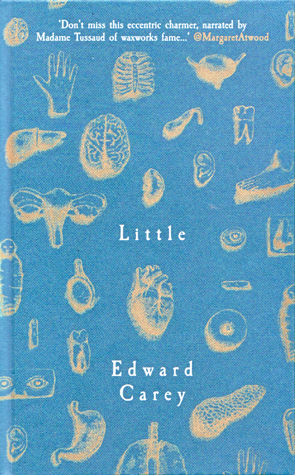

I think Carey’s book has some strengths and weaknesses. The problem any author faces writing historical fiction is how to use the material. One of the book’s strengths lies in the fifteen-year process of immersion Carey undertook while writing, producing art and figures to help him engage with the material. A lot of that is used in the book which I think enhances the reading experience, since his drawings represent Marie’s interpretation of the world and her subjects. The drawings of hearts, spleens, arteries and other body parts are also an important reminder that the basis of the wax works lay in a scientific interest in the human body, not just titillation, since Curtius began his career as a wax modeller for the education of surgeons. However, some of Carey’s more imaginative engagements with the story didn’t make it into the pages of the novel. There’s a scene in which Marie wakes in the semi-darkness to find a figure at the end of her bed. She believes it is Madame Élisabeth, daughter to King Louis XVI, with whom she spent time in the Palace of Versailles, returned to her. She tries to speak to the figure, only to find it is a wooden life-size doll of herself which Edmond, a young man with whom she is in love, has carved for her. It’s a somewhat creepy moment, but the doll, which Carey actually carved, is not pictured in the book.

The wooden figure of Marie Grosholtz/Madame Tussaud, carved and finished by the author

Marie remains a fascinating character throughout the novel. She travels from Switzerland to France with Doctor Curtius as an apprentice to pursue opportunities in wax modelling. Under his tutelage Marie becomes a gifted wax modeller whose opportunities are diminished when Curtius lodges them with the Widow Picot, who takes a dislike to Marie and is determined to have a part in Curtius’s business. Carey also documents Marie’s time living in the Palace of Versailles, officially as a tutor in drawing and wax modelling for the princess ÉLisabeth. Tussaud’s claims in her memoir for this part of her life – as in other parts – remain disputed, but Carey is writing historical fiction, and his portrayal of Marie’s time in the palace is interesting and invests the reader more successfully in the latter revolutionary section of the story. Besides, it offers a believable explanation as to how this poor girl was able to access some of the most famous people of the period, from Enlightenment thinkers like Benjamin Franklin, Rousseau, Diderot and D’Alembert, to royalty, including King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, to later figures like Napoleon.

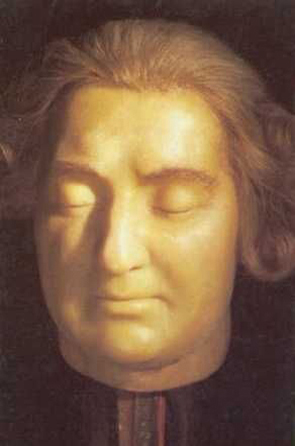

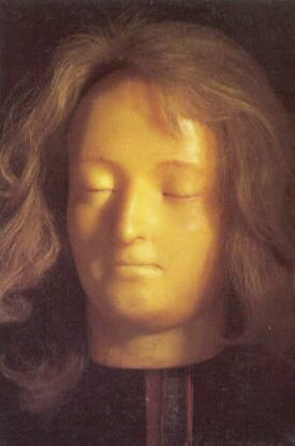

A difficulty in writing about a real person lies in narrative interest. At times the narrative feels a little conventional; largely linear with few flashbacks. Of course, the conceit is that Marie is telling her own story and she has chosen to tell it from the beginning, but the early narrative does not attempt to shape the succeeding stages of Marie’s life, which she presumably knows, so it is not always possible to judge how significant some aspects of the story are. There is some attempt to give the whole thing greater cohesion through the motif of dolls and figures, from the peg doll, Marta, given to Marie as a child by her mother, the many wax figures of the book, the tailor’s dummy that represents the Widow Picot’s dead husband, the wooden doll carved by Edmond or Marie, as well as Edmond’s attempt to hide from the army draft by disguising himself as a doll. Marat, the revolutionary doctor who called for more heads and was stabbed in his bath, is created as a wax figure by Marie and his death mask is sold to his venerating followers en masse. But sometimes Carey’s narrative also suffers from too explicitly using the motif. Having given birth to a stillborn daughter, the diminutive Marie (herself doll-like) reflects, I’m sure it’s my fault I can only ever create lifelike and life -size. What do you expect from a father who was more mannequin than man? What do you expect from a mother who spent more time with imitation people than real ones?

Yet Carey’s story firmly places us amongst real people, even if his representation is somewhat fanciful at times. His placing Marie in the Palace of Versailles, for instance, is one thing, but for Marie to have met King Louis XVI by chance and to have believed him a locksmith for so long, seems a little incredible. The scene in which the king is found fixing a door lock is reminiscent of many incarnations of the mentor figure in the Hero’s Journey narrative structure, which this book loosely follows. Think Yoda in The Empire Strikes Back before his real identity is revealed, or any number of mentor figures whom the hero initially dismisses before their true worth is revealed: Mr Miyagi in The Karate Kid. In this case Carey elicits sympathy for Louis before we know who he is – the man, after all, was beheaded, as was his family – and perhaps it is a nod by Carey to the uncertain veracity of Tussaud’s account of her life, also. It’s a problem Napoleon raises when he meets Marie. He refuses to believe in the existence of Jacques Beauvisage, a revolutionary executioner, until Marie claims him as an acquaintance. Even so, he remains sceptical: This story … is a new one to me. Don’t expect me to believe it.

However, I think the historical interest in the novel transcends the minutiae of Tussaud’s life. What it does successfully is represent on a personal level some of the wider historical and social impetuses of the time. In particular, it helps explain not only the popularity of the wax works, but how it reflected Enlightenment thinking and the social consequences of that. In the wax works there is a kind of egalitarianism, where royalty and murderers might be exhibited in proximity (although traditionalists like the Widow Picot railed against it). This is the attraction of the wax works to revolutionary leaders. It deconstructs power and thereby has propaganda value. I equalise people,

Curtius tells Marie, … that is what they call me, Little, the great leveller.

Curtius’s speech unmistakably alludes to the revolutionary English movement, the Levellers of the Civil War. The potential of wax representation to deconstruct power or to mythologise the revolution is why Tussaud ends up casting so many death masks of victims of the guillotine; why she is pressed into representing the death of Marat. When rioters fail to find Minister Necker and the Duc d’Orléans, their wax effigies stolen from the Palais-Royal serve just as well, thrust atop poles and marched through the streets. Marie and Curtius’s work becomes a record of social upheaval already anticipated in the exhibition created by Curtius, and it has the potential to bring the masses up close to what was once hidden:

Curtius, in his great hall, has abolished privilege! Curtius has dismissed all laws of etiquette. Curtius has done away with class. Where else in the world might a pauper approach a king? Might the mediocre touch genius? Might ugliness draw close – without shame – to beauty? The cabinet is the only place.

Little, page 321

This was interesting to reflect upon, since this tradition of draw[ing] close

continues in the modern incarnations of Madame Tussaud’s. What we have exchanged on the whole, however, is historical significance for celebrity, history for popular culture.

Marie says of their working practices when making the wax models, that each can only focus on one part of the process – casting the face, moulding the wax, painting, inserting eyes or hair – so that each small job contributes to the final whole work. In turn, each figure, whether it be the body of the king, a murderer or a victim, represents the wider society. When Mercier takes Marie around Paris for the first time, he illustrates the metaphor: the Port Neuf bridge is an artery, the Hotel Dies, which acts as a hospital for the poor, is where disease flourishes and a hydrocephalic child is a representation of the class divide in Paris. The head is enlarged at the expense of the rest of society, the withered trunk of the body. The message is clear. The body has political implications. Its representation is a microcosm.

Carey’s narrative includes many other great details and shoehorns in a few more historical personages for good measure. Jacques-Louis David, for instance, is given the job of producing a portrait for Marie even though he never did in reality. The painting featured in the book is by Carey. Luois-Sebastian Mercier, a dramatist and Utopian writer of the time (Paris in the Year 2440) and friend to Marie, is given a gruesome fate of having his feet grow into his shoes in prison. Tussaud spends time in prison with ‘Rose’ who later becomes the wife to Napoleon. At least Tussaud claimed this last to be true. I haven’t been able to find any references to Mercier’s shoes, however.

Finally, Carey’s approach to Tussaud’s life, while fascinating, does not have the same emotional depth or complexity of character as more accomplished historical writers have. Many of the characters remain caricatures. Widow Picot, for instance, remains a cartoonish villain for most of the story, which serves only to make Marie saintlier. Carey’s approach also means the narrative flows but is biographical in its use of material rather than a complete fictional adaptation. I think this shows in the ending which is rushed and really not needed; inserted, it feels, as though the author felt all aspects of Tussaud’s life needed to be ticked off. Madame Tussaud moves to London to save her business. The rest is history. Despite these few shortcomings, this is a fascinating story that gives an insight into Tussaud’s life and times, as well as demonstrating how the idea of wax work exhibitions have evolved for our modern world.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!