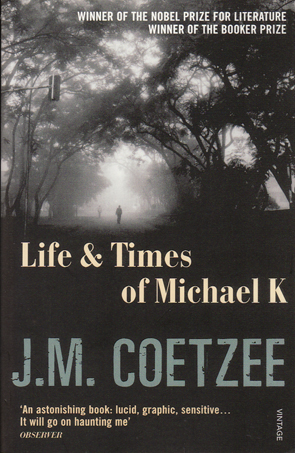

Apartheid is never mentioned in J.M.Coetzee’s Life & Times of Michael K, nor is race explicitly made an issue. Yet the novel was written during the Apartheid regime in South Africa of the 1970s and 1980s and provides a stark alternate reality which underpins several philosophical and moral questions concerning segregation.

Michael K of the title is an obvious allusion to Franz Kafka’s Joseph K. from The Trial. Arrested for a crime of which he has no understanding and trapped within an endless legal bureaucracy, Joseph K.’s plight has invited several interpretations. From a political perspective, the novel can be read as a critical commentary of the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s judicial system. Viewed this way, the claustrophobic atmosphere of the novel is more than just an individual’s psychological nightmare, but allows the individual to represent wider social problems.

The same may be said of Coetzee’s novel. Michael K is a nobody. Consigned by his mother to a state home from an early age because of his slow mind and hare lip, K has few prospects in life. At the age of fifteen he is assigned as a municipal services gardener in Cape Town. He remains in that position until he receives a message from his mother at the age of thirty, asking him to come get her after she has been discharged from hospital. After a riot his mother decides she wants to leave the city and return to her childhood home in the country, a farm.

Coetzee sets his novel in an alternate vision of South Africa. In this South Africa a civil war rages in the countryside and there are travel restrictions which make it difficult for K to achieve his mother’s wish. Like Joseph K., he is first frustrated in his efforts by bureaucracy. He must obtain a permit to travel, but he return home to wait for it. His only mailing address is that of his mother’s former employers’, the Buhrmanns, who have themselves fled the city. When K returns to the permit office, he is asked to fill out the form again, and is threatened when he demands to know whether the permit will, in fact, come.

Coetzee’s narrative is not a representation of reality but of a moral argument. His war is fictional as are the various camps K attempts to avoid unsuccessfully, although in the early 1980s the prospect of conflict under the repressive South African system was real. The camps represent a wider social malaise that is not entirely articulated. The first camp K is sent to is designated for the purpose of protecting the poor, for people without jobs so they won’t have to beg anymore.

Those in the camp are required to work on various projects like road gangs or cropping for farmers in exchange for a small wage they can use to feed themselves and their families. The benevolent intentions of the camp are laid bare, however, first by K’s friend, Robert, who declines to join the Sunday shopping excursion to Prince Albert: I say, if we are going to be in jail, let’s be in jail, let’s not pretend.

Later, one of the camp guards who uses camp women for sex, warns K when says he wants to leave, You climb the fence and I’ll shoot you dead, mister.

Late in the novel, after K has made an attempt at a living on the abandoned farm of his mother’s youth (at least he thinks it is the right farm) K is caught, emaciated and dying, and sent to another camp where he receives the attention of a medical officer who does not believe K has anything to do with the political insurgents who have visited the farm, as has been claimed on his papers. In his frustrated efforts to get K to talk, the truth concerning the camps is laid bare: This is a camp, not a holiday resort, not a convalescent home: it is a camp where we rehabilitate people like you and make you work! You are going to learn to fill sandbags and dig holes, my friend, till your back breaks!

Not only does the camp exist to rehabilitate K physically, but it acts as a ideological re-education centre, typical of dictatorial regimes.

But K, like several characters in this novel, is not ideological. The medical officer says of him He passes through these institutions and camps and hospitals and God knows what else like a stone. Through the intestines of the war.

It is a graphic image, that suggests the war has not only the potential to consume physically, but to consume the very soul of the individual. K naively rejects the notion that he is involved in the wider world he seeks to escape: I am not in the war.

Likewise, the guard who threatens to kill him is not motivated by ideology but self-preservation. Faced with the prospect of being sent north to fight, he tells K, the day I get orders to go north I walk out. They’ll never see me again. It’s not my war. Let them fight it, it’s their war.

Ironically, the war, its camps and ideology are a system under which all might lose their sense of self. When an act of sabotage is carried out by members of the camp, this same guard is imprisoned as punishment with those he formerly guarded.

The genius of Coetzee’s narrative lies in displacement. Coetzee displaces the issues of Apartheid into this fictional war which threatens to consume the weak and the strong. There is little evidence to suggest this connection in the novel – not surprising, given South Africa’s censorship laws of the time – since race is never explicitly discussed, nor is the Apartheid system. But it’s something we feel in the oppressive exploitation of the camp internees and the segregated lives they are forced to lead. Noël, the camp commander, assures the medical officer We are fighting this war … so that minorities will have a say in their destinies.

Noël’s assertion suggests a higher cause, but apart from resisting insurgents who live in the hills – or maybe secretly in the very towns they attack – there is no clearly stated purpose for the war, otherwise. Apart from imprisoning insurgents, the only other group who suffer incarceration are the poor. Yet when K is first captured his charge sheet, his only identifying paper, reads: Michael Visagie – CM – 40 – NFA – Unemployed

. As was typical under the Apartheid regime, he is identified as a ‘coloured man’ (CM).

Life & Times of Michael K portrays several characters who attempt to live outside the bounds of ideology (beyond the reach of calendar and clock

), including the Visagie grandson – from the farm supposed to be his mother’s early home – who asks K to help him hide from the soldiers, to the guard who confides his fear of the war to K, to the medical officer who sees something luminous in K’s refusal to be defined by the system that has imprisoned him. What is threatened by ideology is humanity under the grinding of the wheels of history

; humanity, as defined in the narrative by one’s connection to the primary means of living – of gardening and growing crops, say – and of one’s connection to family that defines a sense of self. These things are fragile : It seemed to him that one could cut a cord like that only so many times before it would not grow again

; there must be men to stay behind and keep gardening alive, or at least the idea of gardening; because once that cord was broken, the earth would grow hard and forget her children.

It is this simplicity that inspires the medic and fosters in him a desire to follow K and understand him, and to seek an answer to the question K inspires: What am I to this man?

In realising his human connection with K, the medic realises that he, too, has become a prisoner of the war.

It is a telling insight, much like the situation of ancient Sparta with its large population of slaves – the Helots – who, to a significant degree, necessitated Sparta’s militaristic culture. The captor becomes the captive.

Coetzee’s novel is written in simple unadorned prose which is quite compelling to read. Apart from Kafka’s influence, I found myself reminded of other novels. K’s journey through war-torn South Africa reminded me of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, not just for the story, but its unsentimental prose. I found myself thinking of Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, also, during the medic’s interrogation of K, although the medic does not have the certainties enjoyed by O’Brien. In the end, I admired the novel for the earnestness of K’s intentions and his insight into his own reality, despite his purported simplicity: What a pity that to live in times like these a man must be ready to live like a beast … A man must live so that he leaves no trace of his living

. There is a level of Taoist assurance in K’s approach to life, that suggests a will that will ultimately endure the ideology that seeks to oppress it. Highly recommended.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!