Letters from Father Christmas is a collection of letters Tolkien wrote to his children over a period of twenty-three years, assuming the identity of Father Christmas, from the time his eldest son, John, was only three years old, until the middle of World War II when his daughter, Priscilla, was evidently outgrowing the fantasy. This is an entertaining and intriguing book. Tolkien was a born story-teller. He transforms a charming but banal family tradition into his own family mythology. Through the agency of the letters, Tolkien’s children gained access to the magical world of the North Pole, where Father Christmas is helped by Polar Bear, a kind of child surrogate, who creates all sorts of trouble with his clumsiness and thoughtlessness, but who is otherwise charming and likeable. Tolkien fleshes out the world of the North Pole with other companions, Paksu and Valkotukka, Polar Bear’s cousins, as well as Ilbereth, Father Christmas’s elf, who later assumes some of the responsibilities for Father Christmas’s correspondence, as well as Father Christmas’s enemies, the Goblins, who attack Father Christmas’s residence, or burrow underground to steal presents. A notable omission from this world is a Mrs Father Christmas. Women often seem marginal in Tolkien’s writing.

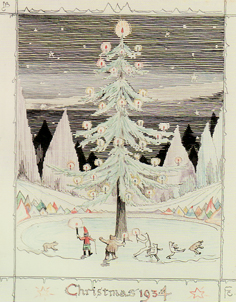

The stories Father Christmas tells Tolkien’s children are funny and magical. Polar Bear is a constant source of entertainment, from his clumsy attempt to rescue Father Christmas’s hood, stuck on the north pole, only to have it snap and send him crashing through the roof of Father Christmas’s house, to foolish attempts to decorate a Christmas tree. There is little doubt that Polar Bear is not just a source for stories, but is a relatable child, just as Father Christmas is a father. Over the long years of writing the letters, Polar Bear takes on various guises and serves different purposes. During the dark days of World War II, when the Goblins are once again threatening Father Christmas’s realm, Polar Bear fights off the Goblins:

Polar Bear is rather a hero (I hope he does not think so himself) … But of course he is a very MAGICAL animal really, and Goblins can’t do much to him, when he is awake and angry. I have seen their arrows bouncing off him and breaking.

Polar Bear has transformed into a reassuring figure of invulnerable strength; a transformation appropriate to the needs of children frightened by the threat of real war. Naturally, this interpretation of the book raises the famous objection of Tolkien, that his stories were not allegories. In his introduction to The Lord of the Rings, he resisted the suggestion that the War of the Ring was a thinly veiled representation of the allies’ struggle against Hitler. But it is interesting how much of Letters from Father Christmas does allude to current events, or speaks of the problems of the times.

In his long letter of 1932, it is not hard to infer that the need for Father Christmas to carry food and clothes to those in need is not just Tolkien’s way of softening the disappointment that the lack of presents in his children’s stockings may have caused, but also references the impoverishment of so many by the Great Depression: I am taking a good deal of food and clothes (useful stuff): there are far too many people in your land, and others, who are hungry and cold this winter.

Even more explicit is the references to shortages and evacuees in his 1940 letter. A group of penguins have migrated to the North Pole to be with Father Christmas and Polar Bear:

Penguins don’t live in the North Pole,

you will say. I know they don’t, but we have got some all the same. What you would call evacuees

, I believe (not a very nice word); except that they did not come here to escape the war, but to find it! They had heard such stories of the happenings up in the North (including quite an untrue story that Polar Bear and all the Polar Cubs had been blown up, and that I had been captured by Goblins) that they swam all the way here to see if they could help me. Nearly 50 arrived.

The importance of this charming story is that Tolkien transforms “evacuees” (in England, often children sent from the city to the country during the London blitz) from victims, into heroes and fighters. His child surrogates shape their own fate. Tolkien’s narrative is empowering.

You get a sense of this throughout the letters. During the lean years of the Great Depression and the War, Tolkien offers longer narratives, entertaining and engaging, which tell of accidents or other adventures which have resulted in fewer presents for that year. What economical riches could not provide, Tolkien’s imagination could.

This engagement with the world is also suggested in the letters’ allusions to religion and history. Father Christmas has forgotten his exact birth date, but he supposes he is about 1934 years old, thereby placing him firmly at the Christian conception of Christmas. He also assumes the name of Nicholas and references famous tales of St Nicholas.

And when the Goblins have their first uprising in the letters, it is their first after many centuries. In fact, it is their first since a very specific year – 1453 – coinciding with the fall of Constantinople (Father Christmas refers to this date twice in the letters) suggesting the Goblins not only threaten Christmas, but are also an existential threat to Christian civilisation.

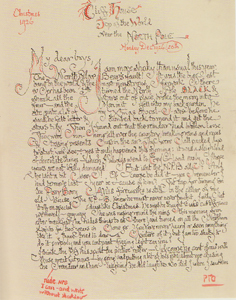

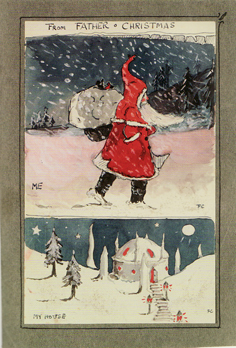

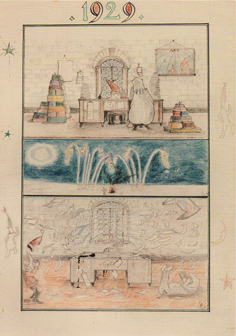

The letters also offer the reader a small insight into Tolkien as a writer and artist. He illustrated scenes from the stories he tells in the letters in the style that is well known to Tolkien fans. My edition of the book has facsimile pages side by side with the text. I bought a hardback edition published by HarperCollins in 2015, but I imagine any illustrated edition would be worth a look.

There are also hints of his more famous stories – their nascent versions, perhaps – in the letters. The Goblins anticipate the Goblins of the Misty Mountans in The Hobbit, as does Polar Bear’s journey into their caverns where he is lost, like Bilbo. There are other tantalising glimpses, too. In the 1937 letter (the year The Hobbit was published) Father Christmas says, I was going to send ‘Hobbits’

directly referencing Tolkien’s book. When under attack from Goblins, Father Christmas blows his golden trumpet, and later blows three blasts on the great Horn (Windbeam)

to call for help against a Goblin attack. The scene recalls Boromir’s horn that he blows when under attack from the Uruk-hai. Prescilla, Tolkien’s daughter, also favours a teddy bear by the name of Bingo. As he drafted The Lord of the Rings, Bingo was the original name for Frodo. One imagines the writer borrowing from here and there in his daily life to shape his epic work.

However, Letters From Father Christmas succeeds as a narrative on its own. The letters are charming, witty and full of the tantalising allusions to a magic world that appeals to children. I would qualify this with the thought that the story works best with the understanding of the letter's written context; that Tolkien was a writer writing for his children. In the end, this offers an adult perspective, a poignant insight into the sad fact of children growing up. Like Christopher Robin, whose story is one of movement from the Hundred Acre Wood into school and beyond, to the world of adulthood, the last letters suggest the loss a parent feels for their children as they grow into adulthood, as Tolkien, one by one, loses his children’s interest or belief in his mythology:

I suppose you will be hanging up your stocking just once more: I hope so for I have still a few things for you. After this I shall have to say “goodbye”, more or less: I mean, I shall not forget you.

Letters From Father Christmas is worth a read. It is both an unfolding story and a work of visual art. Its appeal may be primarily for Tolkien fans, but it also has a general adult appeal. The work is nostalgic and magical. I would imagine that children would easily access it with an adult’s help, too. It would work well if read together, or, even better, to supplant that newish commercial tradition, Elf on a Shelf, with these letters.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!