ISBN:9781783786121

Translator: Michael Hofmann

- Category:Historical Fiction

- Date Read:17 July 2024

- Year Published:2021 (English translation published 2023)

- Pages:294

- Prize:Booker International Prize 2024

It’s a classic trope: an older man meets a younger woman and there is romance. The delights and the dangers are somewhat familiar. Jenny Erpenbeck’s International Booker winning novel, Kairos, is a quintessential older man/younger woman scenario. Hans meets Katharina on a bus and the attraction is instantaneous. Katharina is nineteen and a student in set design. Hans is a writer. Katherina will later discover her father has read his work. Hans has also studied musicology and has a broad knowledge of art, theatre and literature. He’s fifty three years old, married and has a son. Katharina has just been stood up by a young man she will barely remember after this. And now their future relationship moves inexorably into their present with a coffee, a tour of Hans’ apartment, dinner and then a night of passion. Their first moments as lovers are accompanied by Mozart’s Requiem. ‘The dead who lie in the ground are not sleeping but waiting,’ Hans tells Katharina. The music swells as a counterpoint to their love-making, transmuting the scene from ardent embrace to danse macabre:

And now all the crypts are become transparent, and he and she are standing directly in the graveyard, and the island of the living is no bigger than the tiny patch of ground under their feet.

Desire is at its height, the moment is overwhelming and it feels portentous. Hans intends to signal something through the Requiem Mass (“she needs to know what she’s up against here” he thinks as he selects the music) which we may only understand later: there appears to be an anticipation of failure and death in their beginning. We already know Hans will die. The opening paragraphs of the novel tell of his death. But those ghosts that swell the music are not just death, but the past.

The year is 1986. This is East Berlin.

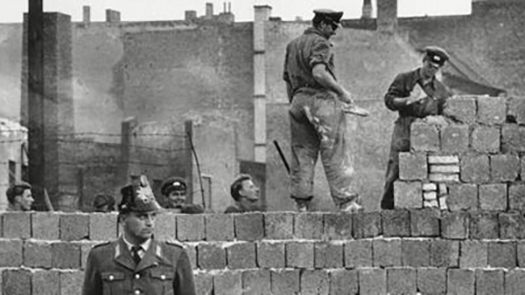

Only three years later, the Berlin Wall will be torn down and East Berlin will incorporate consumerism into its culture, and East and West Germany will re-unite. Behind is the ghost of Germany’s past: World War II, Hitler and the death camps. Hans and Katharina discover that the sum of their birth years “is one hundred. Surely no coincidence! A hundred years and we happen to meet.” The discovery seems propitious – the serendipity of their meeting is mythologised by this mathematical accident: 1933 and 1967=100! But it is also foreboding, for their relationship also represents the German century. There is an older Germany with a Soviet culture which will be redundant, and a younger Germany that will embrace the momentous changes Unification will bring. While ever the wall remains standing and the old system is protected, Hans’ and Katharina’s romance will stumble along, even during its worst throes of abuse and manipulation. But Hans, like the old Eastern Bloc Germany, is a dinosaur and his time seems marked.

The youth/age, west/east dichotomies may suggest a further simple dichotomy of good/bad. And it certainly feels like that, particularly in the second half of the novel. Because the novel focusses on a personal relationship we are most likely to chart the course of that in our imaginings, and Hans and Katharina’s relationship is uncomfortable to watch. Hans is a serial philanderer and Katharina, who is strongly committed to the relationship – she hopes to have a child with Hans – constantly wonders whether she will be cast off like Hans’ former lovers. Yet when Katharina succumbs to an opportunity for infidelity she has long resisted, Hans punishes her in various ways. He begins to brutally apply his strap during sexual play that was initially a titillation with a riding crop. He forces confessions from Katharina, sends her cassettes full of his taped recriminations and self-pity, and erodes her self-esteem. The sophisticated mentor of the first part of the novel – a Henry Higgins to Katharina’s Eliza Doolittle – is diminished in the second by his unrelenting blame-laying, his lack of empathy and self-righteousness. For her part, Katharina may bring herself intellectually to ask why she continues to pander to Hans’ worst instincts, but emotionally she is convinced of her love for Hans. She even echoes the self-destructive declaration of love made by Catharine for Heathcliff: “Hans is she and she is Hans.” For the reader, the relationship seems relentless in its cruelty. I just wanted it to end. Why doesn’t she leave him for one of those other boys? Late in the novel Katharina dreams of a man she would like to marry, but she is carried away by an ice floe, which she realises is Hans.

It’s easy to see Hans as the bad guy. He is certainly an unsympathetic character for much of the book. But Erpenbeck has kind of already warned us not to judge too simplistically: “The contents are not cut-and-dried, art is a process, not a product … Certainly art has nothing to do with a happy ending, says Hans.” Hans is discussing a documentary on the sculptor Stötzer which he and Katharina have just gone to see. His point touches upon an intellectual problem that East Germany will face, pertaining to its own identity and role as it reunifies with the West: whether art is merely the vehicle for bourgeois escapism – a place where Coca-Cola can achieve ascendency over Marxism – or whether East Germany can maintain a distinct character and “present a Socialist alternative to West Germany.” The “sugared pill” that is Western culture would out Hans in this story and reassert Katharina’s identity as a strong woman, no doubt. But less palatable, yet nevertheless crucial to the novel, is a need to try to engage with Hans and understand him through his part in Germany’s past.

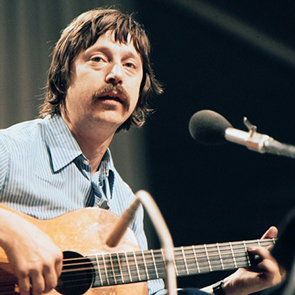

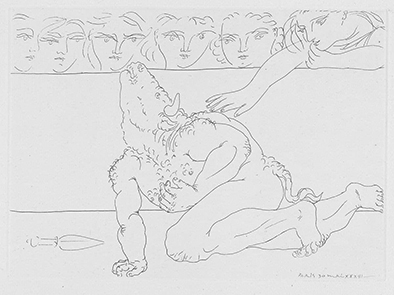

Hans is strongly associated with the old Germany. There’s much made about the age gap between Hans and Katharina, and there are a number of clues about exactly when he was born. The most explicit clue is when he tells Katharina that Picasso made a contribution to the day of his birth. He claims that Picasso drew three scenes featuring the Minotaur on the day he was born. Picasso was interested in the Minotaur as an artistic theme, and drew and painted the Minotaur over the course of his life. The Minotaur connects with the culture of bull fighting in Picasso’s Spain, but in the 1930s it was also interpreted as uncontrolled desire, and was often understood as a representation of Picasso in his own work. The Art Institute of Chicago states in its webpage, “the beast in some ways may have embodied Picasso’s own self-perception as a womanizer.” It’s an interesting parallel to draw with Hans’ character, but the association is also historically interesting. Notwithstanding Hans’ claim, the Minotaur drawings (which he cites and describes in enough detail to identify) were drawn on three separate days in May 1933. But they nevertheless place his birth only months after the accession of Hitler to the role of chancellor in January of that year. Like the Minotaur, Hans is an ambiguous character. In the three pictures the Minotaur is either slain by Theseus, or possibly slain by his own hand, as Katharina notes of one of the drawings. Hans’ life begins with the rise of Nazi Germany and arcs through history to the destruction of the wall. It makes him old enough to have been a member of the Hitler Youth – a photograph of him in uniform is the only one to have survived from his early years – but not old enough to have participated in the war: old enough to have seen the aftermath of the death camps and to have understood what happened, but to have grown-up politically apathetic, nevertheless. Hans is a man haunted by Germany’s and his own past. We learn he opposed the protests of German workers against the Soviet State in 1953, and even helped to undermine them by acting as a ‘scab’. And when he might have acted nobly and signed the Resolution against the expatriation of Wolf Biermann in 1976, he failed to do so. Yet he enjoys the use of an apartment abandoned by a friend who has left East Germany in protest over this event.

Hans, like East Germany, has failed to act; failed to progress. Now, his affair with Katharina is a rupture in his life which we don’t fully understand until the end of the novel; we don’t fully see its personal implications nor Hans’ motivations that turn so sour: why he so suddenly involves himself with Katharina. Like Germany, itself, Hans has seized a moment. Kairos: it’s there in the title. Kairos is a lesser-known god of the Greek pantheon. He represents favourable moments and opportunity. We are told on the second page of the novel that Kairos,

… is supposed to have a lock of hair on his forehead, which is the only way of grasping hold of him. Because once the god has slipped past on his winged feet, the back of his head is sleek and hairless, nowhere to grab hold of.

Hans, whose “hank of hair … keeps tumbling down into his eyes” is a Kairos figure. “Was it a fortunate moment, then” our narrator asks, “when she, just nineteen, first met Hans?” An easy answer is no, but then opportunities aren’t always what they first seem. These characters, like the moribund economy of East Germany, are jolted from their apathy. Time, under the East German regime, has stood still and the country has stagnated. In 1961, “the government walled up time to win time and walled up the people to win the people.” Time goes “fizzling and dangling and reeling” in the throes of the new German revolution, and goes “whooshing” with the fall of the wall. And time dominates their affair. Hans and Katharina secrete time to be together. Then they have a sense of time running out. Likewise, when the new parliament is elected, only to suspend itself – an ominous moment – “Suddenly time is a steel corset.” Freezing and stopping time is associated with the stasis of East Germany and a fear of moving forward. At one point in their rocky relationship when Hans dumps Katharina, Katharina realises that time “feels so sticky, it’s as though it had lost all capacity for passing.” And in another literary nod to Miss Havisham she decides, “The cake, glasses, and flowers that Katharina set out on the table in her attic room in another life will remain where they are for all eternity.”

Michael Hofmann’s translation is excellent. Erpenbeck’s narration is sophisticated and Hofmann skilfully captures the shifting perspective between the characters through their voices, sometimes shifting between them within the course of a sentence. We get a sense of why these characters connect simply through the way their language mirrors and echoes each other, and how dissonant tones and expressions signal their emerging rift. Hofmann’s prose also captures what I imagine must be the poetry of Erpenbeck’s prose. In dream sequences and allusions to mythology, just as much as in allusions to contemporary German history and culture, Hofmann’s representation of the original text feels controlled and precise. Allusions to the Sphinx legend are enough to demonstrate the skill of the writer and her translator. In the legend of Oedipus the Sphinx famously asks him a riddle: What has one voice but goes on four legs in the morning, two in the afternoon, and three in the evening? Oedipus avoids death by answering that a human being crawls as a baby, stands on two legs as an adult, and walks with a stick in old age. It’s another allusion to time which Erpenbeck parodies to illustrate the vagaries of capitalism throughout her novel: “a summer dress is twenty-five-D-marks in the morning, ten at lunchtime, and maybe two-fifty in the evening” Katharina observes when she is given permission to visit family in West Germany. She later uses this observation to justify theft in a new economy that has wiped away the wealth of many East Germans: “Paying nothing at all for the dress is, if you look at it that way, only an especially radical form of this trend.” But perhaps the real point is that Oedipus, in trying to avoid his fate, has also tried to stop time like the East German government in 1961. Fate, or history or economics – call it what you will – can only be held at bay for so long before things change. If that seems like an interpretative stretch, especially since Oedipus isn’t specifically referred to, other allusions to myth pepper the book. That’s the thing about myths: they feel universal in their applicability to human experience. This is a simple story that belies a complex history, told with a sophisticated narrative voice. The characters’ situations may feel depressing, but we owe it to art – if we side with Hans for a moment – to look beyond the hope of a happy ending, and peep behind the curtain.

Art in Kairos

- Dying Minotaur

- Theseus Stabs the Minotaur

- Dead Minotaur

No one has commented yet. Be the first!