Who knows when you might be reading this review of Tim Winton’s Juice? Maybe it’s January 2025 shortly after I’ve written it, or sometime later this year, or maybe just a few years from now. Or perhaps it is sometime in the future. The future, for our purposes, isn’t next year or five years from now. It’s a time we can’t quite imagine, when technology or politics or the world has changed in ways we can’t entirely predict. Maybe you’re the last of a small collective ensconced in the former United States of America, your people descended from preppers who thought to maintain computer systems, not just stash food and guns, and you’ve found a server which you’ve managed to breathe back into life, and you’ve discovered this website, and the first thing you did was read this particular review because somehow, someone from the early days of your collective preserved a copy of Winton’s book, and it’s the only thing you’ve ever read. And the climatic heat and the struggle to survive described in Winton’s book is something you can identify with. The suffocating ash that cloys the surface of disintegrating roads. The difficulty of trusting strangers. Wondering exactly what went wrong because records are sketchy. But somehow, you still know that whatever went wrong in that mythical time that is my now of the twenty-first century, it was because things were done wrong, opportunities were missed; that greed and corporate mendacity outweighed the common good and everything went to shit.

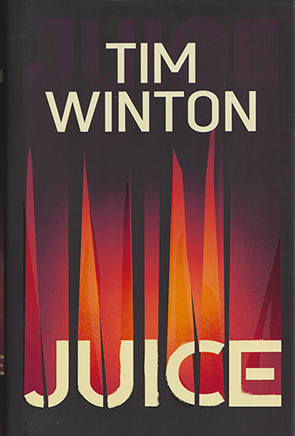

That’s an approximation of the world imagined by Tim Winton in his first science fiction novel. Except, Winton is an Australian novelist and the world he writes about is primarily set in Western Australia, hundreds of years – the exact timescale is unclear – in our future. Winton’s narrator, who is never named, flees across the desert with a small child whom he has promised to protect. They come across a mining site which promises hope for survival, but they are captured and imprisoned by a man wielding a crossbow. Forced to tell his story to keep the bowman from killing them, or until he can find a way of escape, our narrator hopes he can inspire some humanity in their captor, whom he perceives shares a former ideological cause. The premise of the novel is already literary (allusions to other works are peppered throughout). Our narrator is a futuristic Scheherazade, spinning out his tail and drawing us in.

The narrator, we learn, has lived with his mother (also unnamed) on a homestead somewhere north of Perth most of his life. His father died when he was seven. Summers have become so hot due to climate change that it is not possible to survive outside between the Tropics of Capricorn and Cancer during summer. Populations on the planet are therefore shifting either south or north of the tropics. But homesteaders like the narrator and his mother, who live somewhat more remotely further north of the main populations, are tough people. During the summer months they make a life for themselves underground and have learned to produce crops in these harsh conditions. The economy is essentially a barter economy, and the narrator goes to the nearby hamlet on trading days to acquire materials needed on their homestead in exchange for their surpluses. As he gets older, he builds his own truck rig and goes on journeys to forage for supplies. Despite these conditions the narrator is raised to believe in the Panglossian mantra that he had “been born into the best of all possible worlds.” Dr Pangloss is a character in Voltaire’s Candide. He is an overly-optimistic character who often asserts that we “live in the best of all possible worlds”. This is despite the fact that many terrible things happen to Pangloss during the course of the novel.

Candide begins with Candide as a student of Professor Pangloss, who has indoctrinated him with Leibnizian optimism. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz postulated in his 1710 book, Theodicy, that God’s actions are just, an argument which he used to try to address the problem that God is purportedly all-knowing and all-powerful, but allows evil to exist. Leibnitz’s idea was that God’s purpose could not be known, but that he acted justly, even when it appeared otherwise. The harsh trials faced by Candide and Pangloss shake Candide’s faith in his teacher. Instead of a belief in the best of all possible worlds, the novel concludes by advocating that “we must cultivate our garden.” That is, we are responsible for the world we create and the lives we live. It is the bowman who intuits this Panglossian streak in the narrator, but it is Sun who reacts to his abject acceptance of what life offers: that “Nothing’s forever”. “I hate that old saw,”, she says, annoyed. “That attitude really shits me. Nihilism.” Under his mother’s tutelage the narrator has accepted the advantages they enjoy over others in their world, and has settled for a contented purpose within his world’s parameters. The course of the novel shows us how, like Candide, he is disabused of his Panglossian outlook.

As readers, experiencing this world for the first time, we feel a disconnect between this disposition and reality. Despite the dramatic opening of the novel – their flight and capture – we are aware that this world is not the world of Mad Max: not yet. Although we sense it as a future possibility. The narrator’s mother raises him to believe in egalitarianism and fairness. The world in which the narrator is raised is one of principle and order; a world still predicated upon morality and values. The narrator explains to the bowman that he is descended from a people who lived in the shadow of an enormous fig tree with a huge underground reservoir of water beneath. He is of the Children of the Plain, a people who were once the Children of the Tree. This sense of belonging, of a society, is important. After their people left the protection of the Tree the narrator’s family began to undertake annual pilgrimages to it, and would descend into the cave that had once been the reservoir. There are religious overtones here. This atavistic return feels like yearning for a paradise lost. But the narrator’s mother characterises their life at the Tree as a refuge and “every refuge is a form of captivity,” she says. Instead of losing paradise, she asserts, “We came down onto the plain into paradise, not from it.”

It is an argument that turns centuries of the human condition based on a Prelapsarian narrative on its head. As readers of Winton’s novel, we understand that the hamlet and homestead are not a Paradise. Sun, a young woman from the city of Perth who comes to the hamlet as a trainee vet and marries the narrator, is distressed by the harsh summers which necessitate life underground. Climate change, which made life under the Tree unbearable as the water table rose and its reservoir salinised, is creating even harsher conditions and is further degrading the quality of life; the possibility that life might continue on the Plain at all is questionable.

All this places the past directly at the centre of the narrative in order to make sense of what is happening, although knowledge of the past is vague. A sense of moral integrity is defined against the proclivities of a past world that is clearly set within our own present. The narrator and the bowman speak of the past in mythic terms: of the Dirty World of oil and petrol, of the Terror, a period of social breakdown whose very name recalls the chaos following the early days of the French Revolution, and the Long Peace, when society was restabilised. Words like ‘overlords’ and ‘oligarchs’ are used to describe capitalists and their regimes whose accrued wealth and hidden networks are still perceived as a threat to the viability of this future world, should they ever regain influence.

Set against this history, the Fall of humankind is not represented by this future society forced to survive the extremes of climate caused by wanton exploitation of the Earth’s natural resources, but the set of practices of our own time that will bring this world into existence: a set of practices likened to a devouring beast:

Of course, the Dirty World was rotten to the core. It seems too good to be true because it was. Every miracle came at a cost – a river poisoned, a people enslaved, a species or language expunged. It was a monster that devoured everything in its path, including its children. Then it gorged on the future, which is to say its children’s children. Unwitting, at first. Then by design. Some faked ignorance. Others pretended to care and promised to change course. But all along the most powerful knew what was coming, what it was costing. They hid that knowledge. Buried it. Confused it. Diluted it. To gain advantage, accrue more riches, and, finally, time enough to prepare themselves for flight.

The imagery of cannibalism – of capitalism eating its children like the god, Chronos – speaks to the judgment of depravity made against our world. Our humanity is flawed. The worst that can be said of anyone in this future world, beyond that they are thieves or murderers, is that they are cannibals. The narrator suggests the bowman may be a cannibal, of desiring “unconventional sustenance”, but withdraws the accusation when he sees the danger of making it. When the bowman speaks of the ‘Hermit Kingdom’ (presumably what is left of China, where Sun is from) he uses cannibalism as a racial slur: “They say they eat their own over there.”

The descendants of these criminal oligarchies, the capitalist enterprises that degraded the world and “gorged” on it, now live ensconced in remote fortresses, protected by their technology, by servants, even slaves, and Simulacra, or Sims, artificial people with physical capabilities beyond ordinary humans. Against the advantages held by the oligarchs and criminal families, by virtue of their wealth and access to technology, is pitted the will of the Service, a worldwide organised resistance, bent on eliminating the last vestiges of the oligarchs and their power with extreme and pitiless force.

This is one of the most interesting aspects of the novel, and certainly provides some of the most intense and harrowing drama. Tense episodes showing the determined will to oust these remnants of a destructive class by any means: with blunt and bloody force using terrible weapons. But at the same time, we are unsettled by these actions, as much as they might appear a justified, or perhaps a rational response to the perceived danger posed by the past. The language used to describe the descendants of capitalism is impersonal, even degrading, as is the language used to describe actions taken against them, which is couched in neutral and clinical terms. Victims of these cleansing missions are ‘objects’, their elimination is ironically termed an ‘acquittal’. The work of the Service is described in religious terms: “our cause was just, our faith was strong”; “the work was holy.” In contrast, the remnants of the oligarchic regimes, “clung to the language and culture of a fallen dispensation”, a phrase recalling Eliot’s poem, in which the Kings from the East realise the error of their own religion upon seeing the infant Jesus. In short, these people were misguided; ignorant. While we may identify with the cause of the Service, we should be aware of the partisan propaganda that inspires their cause and their belief that they are more than players in human history. It is the creed of every despotic regime.

All that genius, she said. All that potential. So much of it wasted on bastardry. Lies. Empires. Slavery. That was not inevitable.

Juice, page 357

The narrator, who has taken part in these killings, tells the bowman, “I straightened up and felt myself slowly fill with juice.” Of course, this is an interesting expression, given the title of the book. It suggests he is filled with the righteous sense of his mission and its accomplishment. The word is used with various meanings in the narrative: it is used to mean excitement (“I was juiced up and twitchy”); determination (“the surge of juice in your veins”); courage (“You’ve got juice, I’ll give you that”); and enthusiasm (“I’ve still got the juice for it”). But the use of the word also suggests a shift in moral understanding, from the utilitarian ‘juice’, meaning petrol or energy stored in batteries, to an understanding of the cost associated with acquiring that juice, moving the towards a greater association with spirituality or one’s humanity. The closest the narrator can approximate this is through a connection to a place, and by remembering the Aboriginal peoples of the past (known as ‘The Countrymen’). Aboriginals seem entirely absent from this future landscape; except the remnants of their culture the narrator finds in an overhang. We know he places importance on place as part of his own understanding of himself and his world because he takes Sun to the old Tree and cave to show her his origins, and later abseils into the cave with her. He also takes Sun to see the haunting remains of the Countrymen’s culture in the overhang. These remains speak of a people far more in tune with their world, which is so much older than the world of the narrator’s people (“Those who were here before. Actually, before there was a before”) who preserved a memory through their sagas; an understanding of their past and origins, and a connection with the land. The narrator and his people have similar ‘sagas’, but they are the remembered verses of the Christian Bible, usually quoted by the narrator’s mother as part of his moral education.

Though it is the narrator who introduces Sun to his special places, it is Sun who intuitively understands the appeal of a direct relationship with the earth, though she comes from the city. After they visit the overhang Sun considers that with imagination their life might be other than it is: that they might have just “lived like nomads on the road […] just being in the world, not trying to … shape it.” Already, after they have visited the Tree, Sun has suggested that people “fall out of love. With their home. With the world. They end up destroying themselves. And everything around them.” She describes the process as going dry: losing “their juice”. Implicitly, ‘juice’ is also that connection with life, with the world, that is the measure of an understanding that a system which exploits the Earth and its resources has lost sight of.

In this sense, the story of the People of the Tree, who abandon their world for a life on the Plain, has parallels to our own story in the twenty-first century. The world which the narrator’s people inhabit may have already been fated against them by our own generation, but their response to environmental degradation somewhat reflects our own:

But the water in the cave began to take on a worrisome taint. And for a while – too long – the people suffered doubt and denial. They delayed, telling themselves that the hint of brine in their spring was imaginary, just alarmism. They told themselves that the tree and the cave remained their best protectors. That all would be well while they hid and did nothing.

The water in the cave literally dries out, its ‘juice’ absorbed by the changing climate.

The degradation of the environment runs in tandem with the degradation of the human condition; with the degradation of social structures and mores. Unable to tolerate the increasing heat, society faces a challenge. Already there are signs that things are falling apart. Against this are the Sims, machines used for labour, but with an artificial intelligence that allows them to ponder their place in the world and their relationship with humans. There is a suggestion of slavery in the lack of autonomy they have over their own existence, and their uncanny resemblance to humans which makes them sexually desirable to owners, even though, concomitantly, they inspire revulsion. The bowman deplores Sims. The narrator explains that their “almostness – made my skin crawl.” But the narrator also owes his life to Sims, who asked nothing in return for their help except “honourable treatment”. Their fair dealing and integrity form a juxtaposition to the dishonesty and depravity of humans, willing to cheat, steal and even murder to fulfil their own needs.

It’s a sad reality through much of Juice. Despite the high-minded intentions of the Service to pave the way for a better future by eliminating the oligarchs, there is a sense that every human endeavour, no matter how well-meaning, is tainted by ‘juice’: that need for energy and a purpose beyond the world of nature, which inevitably is corrupting. Maybe it is because the Sims are unaffected by the extremes of the climate and need nothing other than the rays of the sun to ‘juice’ them up, that they remain morally elevated above humans. No matter how well-intentioned the Service is, or what progress the narrator feels he is making in life, the Sims are the only pure thing, in the absence of Aboriginal culture, which bears the potential for a better humanity, more attuned to the world. The novel implicitly asks us for consideration: do we have a chance or are we doomed; is knowledge empowering or does ignorance naturally trump it; and what do we owe the future?

. . .everything lives and dies at the mercy of our ideas.

Juice, page 66

I was reminded of other texts as I read Juice. Surely there will be some comparisons made with Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, although that is a far bleaker novel: more post-apocalyptic rather than dystopian. The same applies for Mad Max, though aspects of Winton’s novel feel like they’re going that way, too. I also thought of Kevin Costner’s Waterworld, a film much reviled upon release though it cost a whopper. Costner’s world is flooded while Winton’s is becoming a desert, but for those who are familiar with this book and the ending of the movie, an obvious comparison can be made. That’s all I can say to avoid spoilers. But what we should understand from Winton’s tale is that the oligarchs are already among us, and the gorging of the world has been going apace for some time.

If you are reading this sometime in the future, I hope there is some hope in things for you. As I sit here, finishing the final lines of this review on the 12 January 2025, wildfires are ripping through Los Angeles. The big headline is that many famous actors have lost their homes, and there is also the question of what Donald Trump, the President-Elect, will do if there are future disasters like this to be handled. Elon Musk, the richest man in the world, who may or may not be holding Trump’s puppet strings, is accused of allegedly cheating on popular video games by turning to loopholes and hiring better players to play for him and raise his ranking. Thus, Rome burns while Nero fiddles.

Juice is well worth the read. It’s topical but it’s also a great story, and I have avoided spoilers so you can enjoy it, too. Buy Juice if you can. Support authors: “Every action is the fruit of an idea.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!