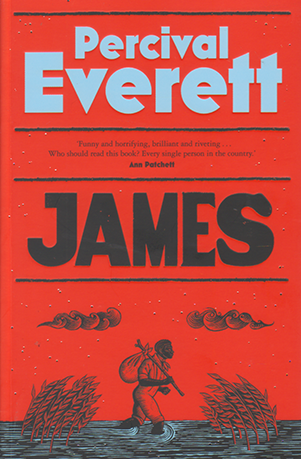

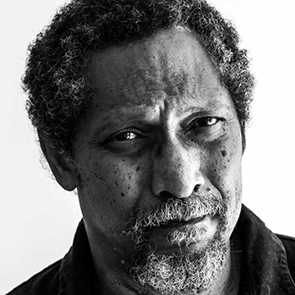

A role reversal in film or literature can be used to challenge dominant ideologies and paradigms of power. This is roughly what happens in James, Percival Everett’s loose retelling of the Huckleberry Finn story from the perspective of Jim, Miss Watson’s slave from The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. In Huckleberry Finn, Jim escapes and flees to Jackson’s Island after he learns he is to be sold further South and separated from his family. Huck also flees to the island after faking his own death, to escape his violent father. There, Huck and Jim meet up and begin a journey down the Mississippi River. But Huckleberry Finn is Huck’s story and Jim is really a minor character. He is most relevant to the plot in the final section of the novel when Tom Sawyer re-enters the narrative and makes Huck and Jim commit to a protracted and rather ridiculous escape plan, mainly for his own amusement. Jim doesn’t really understand the bookish fantasies that inspire Tom, but he is a slave and he is used to doing what is asked of him. In the end, it all turns out right because Tom has known all along that Jim has been granted his freedom in Miss Watson’s will. It’s an awkward plot twist that never really balances with the torment and terror Jim has needlessly endured.

James is not merely a straight retelling of Huckleberry Finn from a new perspective, even if it starts that way. It begins with a scene from the second chapter of Huckleberry Finn. Huck and Tom play a trick on Jim and Jim reacts with exaggerated fear, that he has been meddled with by witches. In Twain’s original, Huck, Tom and other characters are superstitious and fear the supernatural. But in James we see immediately that Jim (or ‘James’ as we will come to know him) is not superstitious, and that if he plays along with the boys’ shenanigans it is from a pragmatic understanding that, “It always pays to give white folks what they want”. Jim isn’t what he seems: there is the submissive slave, Jim, known to his owners; and then there is the intelligent man, James, who deplores slavery and slavers, and desires freedom most of all.

This is the role reversal central to James. That James can speak and think within white paradigms. The earliest example from my experience of this sort of thing is from my reading as a child: the protagonist in Roald Dahl’s The Magic Finger, has the magical ability to turn a family of duck hunters into the hunted. It’s not hard, even for a child, to draw a conclusion from that moral equation.

I also watched the original Planet of the Apes movies and television series when I was young. I’m not so familiar with the new films which started in in 2011 (I saw the first) and let’s not mention that atrocious adaptation in 2001 starring Mark Wahlberg (Oh, I did!) When I was younger the movies were a fantasy, but recently when I thought about them again their use of apes as a metaphor for slavery seemed obvious. I thought about the racial connotations of the apes and humans. A world ruled by apes turns the power dynamic of humans/animals on its head (I am reminded of Animal Farm here, too!). As a speculative metaphor for slavery, it seemed quite neat – turning those ducks into hunters, hunters into ducks – except that we are now likening African Americans to gorillas. I think the makers of the original film had a good idea, but in that detail, they hit an unfortunate wrong note. Even so, one of the memorable moments from the original movies is from Escape from the Planet of the Apes when Zira refuses a banana because “I loathe bananas!” The idea that apes can act and think autonomously – not just parrot humans – is revolutionary. Cornelius explains:

They became alert to the concept of slavery. And, as their numbers grew, to slavery's antidote which, of course, is unity. At first, they began assembling in small groups. They learned the art of corporate and militant action. They learned to refuse. At first, they just grunted their refusal. But then, on an historic day, which is commemorated by my species and fully documented in the sacred scrolls, there came Aldo. He did not grunt. He articulated. He spoke a word which had been spoken to him time without number by humans. He said ‘No.’

In short, an autonomous mind, articulated freely, is a measure of humanity and freedom.

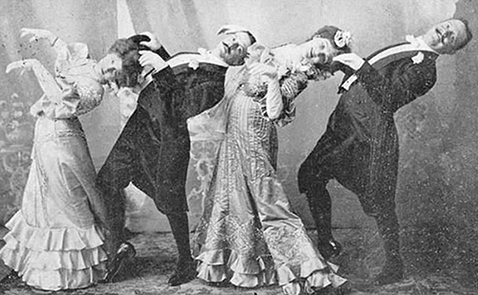

Another example, again from the 1970s, is from one of my favourite movies, Blazing Saddles. In an early scene Lyle, a white overseer, encourages his black workers to sing “a good old nigger work song.” They respond, instead, with a rendition of ‘I get a kick out of you’ by Cole Porter, originally sung by Ethel Merman. Lyle stops them, frustrated, and demonstrates what he wants with a rendition of ‘The Camptown Races’, a song from the Minstrel tradition, now largely thought of as racist. He is joined by other whites, and they begin to strut about ridiculously, aping the black stereotypes their black workers have refused to reinforce. Again, the satire is obvious and the racist white men make themselves look absurd by their prejudice.

James, likewise reverses stereotypes about race and slaves, some drawn from Twain’s original, but also appearing in a myriad of movies and other texts that depict black slaves as unsophisticated. When Jim calls to the boys “Who dat dere in da dark lak dat?” we are in familiar territory. This is stereotypical slave speech; Jim’s “slave filter”. But when James speaks about a white to another black man – “when we see him staggering around later acting the fool, will that be an example of proleptic irony or dramatic irony?” – we are aware that Everett is overturning prejudicial expectations. Out of hearing of his white masters, James’ speech is conventional and sophisticated. He can read. He can write. He is far more sophisticated than the whites who assume their own superiority.

This is the essence of James. James is a thinking, intelligent man who is motivated by the same needs and desires as any other man: to protect his family and be accorded dignity, for a start. The importance of the novel is that it takes submissive Jim, the slave, and reveals him as James, a thinking man who is far more aware of his situation than the white slavers who own him: a man who reads Voltaire, Montesquieu, John Locke, Rousseau, even Kierkegaard.

For those interested in reading this novel, the obvious question is, do I need to read Huckleberry Finn before I read James? I don’t think you do. It stands as a story in its own right. But I think your reading of James would benefit greatly from a reading of Twain’s original, first. I read both Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn first. A quick scan of the opening of Huckleberry Finn will show you that its beginning is based on the end of Tom Sawyer. If nothing else, the three books, together, offer an interesting evolution of character and progressive levels of narrative sophistication.

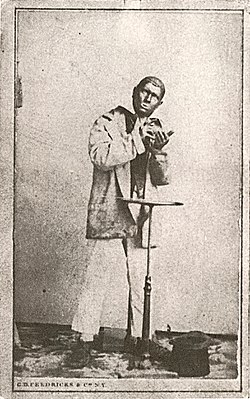

Another thing about reading Huckleberry Finn first, is that it is easier to appreciate what Everett is doing with the story. Everett is fairly faithful to the original for about the first third of this novel. But the feud between the Shepherdsons and Grangerfords is quickly dispelled, and the plot around the Duke and King is severely truncated. Instead, Everett shifts his setting to around 1861, the beginning of the American Civil War. He even abandons the fiction of St Petersburg and begins the story in Hannibal, Missouri, where Twain grew up. Huckleberry Finn, by contrast, is set sometime in the 1830s when the abolitionist debate was not as politically strident. Twain’s novels are appreciated because they encapsulate aspects of the American character: independence; aptitude; adaptability and gumption. But Everett makes slavery and race the central question of America’s character. Twain’s story never quite separates from the boys-own-adventure that is Tom Sawyer. Everett’s does. He breaks with Twain’s plot and he dots his narrative with references to black men notable for their struggle for freedom in ante bellum American. Men like Venture Smith, a black slave who bought his own freedom and recorded his experiences in his autobiography. Smith appears to be a model for James, who bears the burden of a pencil that another man died to steal for him. James needs to be the master of his story, but he is also burdened with the imperative to tell it, demanded by, if by nothing else, the provenance of the pencil. Or there is Denmark Vesey, a black leader who bought his own freedom and became a community leader. Vesey planned a revolt against slavers in Charlston, with the idea that he and his followers would escape to Haiti. Vesey was betrayed and his plan thwarted, but Everett is interested in the imaginative potential of black revolt that men like Vesey inspired, an idea he exploited in his 2021 novel, The Trees, in which dead black people re-animate to exact retribution on whites. In that novel Everett also references the story of Emmett Till, a young boy who was lynched after he was accused of flirting with a white woman. Till’s story would be anachronistic in James, but Everett still invokes his story: “I recalled a young slave who had chanced a look at a white woman. The end of the rope that had named him had been left in the tree as a warning to all others for years.”

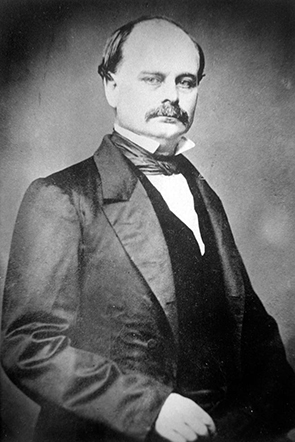

Everett’s greatest imaginative digression from Twain’s original is in the figure of Daniel Decatur Emmett. Emmett is taken from life. He was a composer and entertainer during the period this book is set. He was the founder of the first troupe of blackface minstrels. Emmett’s group would ‘black-up’ – make themselves dark like negroes, with boot polish or other materials – and sing songs for the entertainment of white people. Stephen Foster’s ‘The Campdown Races’ was in this vein. Emmett’s most famous composition is ‘Dixie’ (also known as ‘Dixie's Land’ and ‘I Wish I Was in Dixie’). The song is often sung with a jaunty swagger (but Elvis Presley also recorded it with an impressive vocal and orchestral backing that imbued it not only with Southern pride, but religious gravitas). There are many white villains in this novel, but Emmett is perhaps one of the most interesting. He is a man who claims he is against slavery, but he writes racist lyrics and acts like a slaver. Caught in his power, James realises that there is more than one type of slavery: not just chattel slavery, but bonded slavery, which is a condition many still find themselves in.

For me, the most powerful aspect of James was the notion of identity. It is difficult to maintain one’s humanity and sense of self when these things are torn away by a system that is predicated upon physical force, by prejudice and stereotypes that are meant to dehumanise. James feels the burden of telling his own story – to use the pencil that has come to him – as well as overcome the socio-historical moment which posits that he is less than human. Through James, Everett is appropriating a story that has previously been the purview of a white story teller. As much as Everett is appreciative of Mark Twain’s “humour and humanity”, he seeks to overturn the implications of Twain’s text: that Twain was not only offering a story but also a voice for the American South. He spoke authoritatively in his explanatory note of his knowledge of Southern dialects, including the “Missouri Negro dialect”. Now, Everett has reclaimed the right to speak in a black voice that isn’t a parody of slaves aping slave owners aping slaves: like black and white minstrels trying to be black and offering that culture to a white society as authentic. Whatever the reality may have been in this regard, James’ assertion of a new voice is an assertion for equality and humanity.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!