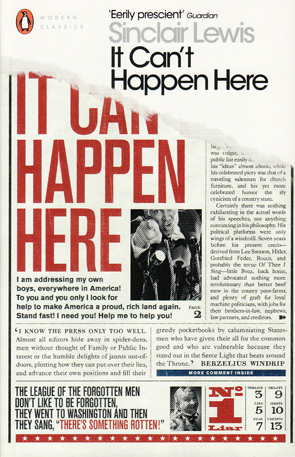

As I neared the end of Sinclair Lewis’s 1935 novel, It Can’t Happen Here, I began to reflect on its relative obscurity. I purchased a 2017 reprint in Sydney after being intrigued by its implicit association with Donald Trump on the cover of this new edition. The back cover selectively quotes the novel, suggesting its fictional President Windrip is a liar

and illiterate

, two accusations that have been levelled against Trump. Set in the 1930s, the novel is a compelling alternative history of the two years following its publication. Roosevelt is ousted as the Democratic candidate and the fascist Windrip rises to power, his administration thereafter mirroring some of the worst atrocities committed by rulers like Hitler and Stalin. Its title is unsubtle in its irony. Lewis’s thesis is that America is particularly suited to tyranny (Why, there’s no country in the world that can get more hysterical – yes, or more obsequious! – than America … Why, where in all history has there ever been a people so ripe for a dictatorship as ours!

) and that the worst of human nature is not particular to the current crop of world dictators.

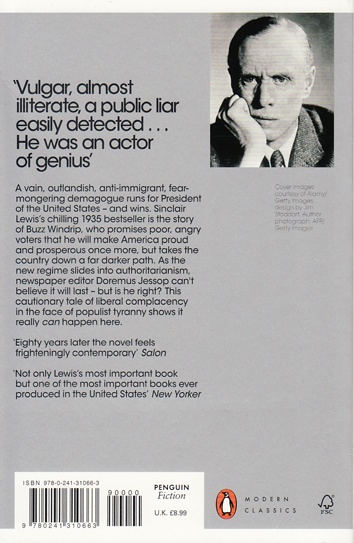

Lewis’s novel has not gained the same distinction as other novels in the dystopian genre, a fact made plain to me as I’ve walked past our local second-hand bookshop lately. I’ve been mildly amused to see a sign out the front which was drawn by the proprietor. It featured a Venn diagram with the titles of four famous dystopian novels, all recognisable even for those who have never read them. It was arranged in such a way to suggest that our current reality has realised the worst that these novels predict. I intended to photograph the sign this morning to include in this review. But in the way of the universe, the proprietor was inside the shop before opening, having finally decided to change the sign after several weeks of thinking it rather clever.

I was informed, however, that her sign was not as original as I had thought, and was directed to look for it on the Internet. This is the diagram:

Our local proprietor had linked the diagram to President Donald Trump and his administration by a comment beneath. Several current situations around the world may have attracted the same association, but Trump looms large in everyone’s thinking, and talk of impeachment and next year’s election isn’t going to make that go away. (When I was in our Sydney bookshop, I saw there were enough books about Trump to keep me reading for the next year, including a mock-epic poem, The Trumpiad, no doubt based on Alexander Pope’s epic satire, The Dunciad. There were even two editions of the Mueller Report, redacted as it is.)

Yet, to insert It Can’t Happen Here into the above diagram would require it to be placed at the centre, pretty much where we are encouraged to imagine ourselves. That is, it seems to have something in common with all four novels. Like Nineteen Eighty-Four, Lewis’s novel shows the importance of misinformation for the maintenance of tyranny. It also reflects on the cult of personality, the religious fervour associated with leaders like Stalin, whom Orwell drew upon as his model for Big Brother. The adaptation of conservative social creeds by Windrip’s administration – the repression of women through the denial of the vote and their being forced from the workplace – echoes some of the feminist issues of The Handmaid’s Tale. The repression of subversive

ideas through the burning of books and the arrest of liberal intellectuals recalls the main thesis of Fahrenheit 451. Brave New World, the only novel written prior to It Can’t Happen Here, depicts a society unmoored from traditional morality and attachments of consanguinity. Instead, it is a society whose only rationale is derived from the tenets of mass production and consumerism. Lewis’s militaristic Corpo army similarly serves the interests of big business and the rich, while pandering to the hopes of the poor.

What differentiates It Can’t Happen Here from these other classic – I am considering its relative obscurity here – is that its portrayal of tyranny is somewhat more prosaic, and possibly that it takes a far more contemporary approach to its subject. Each of the four classic texts displace their issues into societies of a distant future (Orwell’s is the closest in temporal setting to its publication, but still distant enough). Lewis published his novel in 1935 and its narrative starts about mid-1936. Since Roosevelt was still president he had to be written into the narrative. He is challenged by Senator Berzelius Windrip for the democratic ticket. Roosevelt loses to Windrip and so forms his own party, the Jeffersonians, while the Republicans field the fictitious Senator Walt Trowbridge as their candidate. It is interesting to note that while Trump is portrayed as dictatorial, among other things, the threat in this novel does not come from the conservative side of politics. Roosevelt is replaced by Windrip, but his New Deal, seen as antipathetic to Wall Street which presided over the 1929 crash, may be satirically displaced and exaggerated in some of the policies of Windrip, which are distinctly Socialist, despite the public rejection of Socialism in the novel. Windrip’s rise represents the fear at that time that a tyrannical leader was more likely to emerge from the left of politics, given the example of Russia in particular, rather than the right.

The novel’s protagonist is Doremus Jessup, a small-town newspaper editor from Fort Beulah. Jessup is disturbed by the fascist aspects of Windrip’s platform and eventually is drawn into a struggle against Windrip’s regime. Doremus Jessup is most like Winston Smith when comparing him to the protagonists of the four classic novels. He believes in objective truth and is eventually forced to defend it subversively. He has an affair with Lorinda whose beliefs mirror his own, but their relationship does not bear the same political import as that of Winston Smith and Julia. Neither is Jessup’s eventual imprisonment and torture as revealing of the ideology of the state, or its implications. Imprisonment and torture in Windrip’s regime is a blunt instrument of oppression, rather than the chilling totality of control, not of the body and actions, but the mind and thought that is Nineteen Eighty-Four. It Can’t Happen Here, unlike the four classics, is not so much interested in dissecting the machinery of oppression, as it is in putting forth a credible argument that it is possible through its scenario.

The novel’s historical specificity is most likely the reason it has not achieved the distinction of the above classics. It is of a specific time, and for novels to attain a classic status they have to have something to say to future audiences. Huxley adopted Henry Ford as a cult-like figure for Brave New World in order to represent the ideals of the World State. Orwell used Stalin and his regime as a template for oppression. But in doing this, each author also gave their narratives a universal appeal. Yet, there is much that is perceptive and prescient in It Can’t Happen Here, and aspects of the book will seem familiar to a modern reader: The Great Depression that helps to create the disaffected audience of Windrip’s campaign reminds us of Trump’s Deplorables

who suffered under the GFC of 2008. The newspaper empire of William Randolph Hearst (Hearst, himself, was satirised in Orson Welles’s 1941 movie Citizen Kane) is a staunch supporter of Windrip, much like Fox News supports Trump.

But the comparisons can be made more broadly than that. Norman Berdichevsky saw Barrack Obama’s popular rise in the 2008 election as typical of the populism Lewis warns against. Now, Trump, too, is popularly compared to Windrip, despite the many differences between the two leaders: not only for their political parties they represent, but their ideologies. Trump is avowedly a capitalist and would have nothing to do with many of Windrip’s policies, nor has he been able to escape the weight of Congressional and judicial oversight that Windrip sweeps aside by force. Yet Windrip’s isolationism does feel like Trump. And Trump’s character feels oppressive and unpredictable to his opponents. The comparison feels right, even if Lewis’s subject is very different.

While It Can’t Happen Here lacks a singular perspective that memorably encapsulates the mechanics of totalitarianism in each of the four classic texts, it nevertheless offers its own insights into the problem of political power. Doremus Jessup, a mouthpiece for Lewis it would seem, is a Liberal thinker who eschews the oppressive impulse of any political creed, yet is open to the potential of any ideology to progress the human condition.

He was afraid that the world struggle today was not of Communism against Fascism, but of tolerance against the bigotry that was preached equally by Communism and Fascism. But he saw too that in America the struggle was befogged by the fact that the worst Fascists were they who disowned the word Fascism

and preached enslavement to Capitalism under the style of Constitutional and Traditional Native American Liberty.

. . .

I am convinced that everything that is worthwhile in the world has been accomplished by the free, inquiring, critical spirit, and that the preservation of this spirit is more important than any social system whatsoever. But the men of ritual and the men of barbarism are capable of shutting up the men of science and of silencing them forever.

The use of religious language – preached, ritual – to oppose science, and Lewis’s characterisation of the dichotomy as tolerance against bigotry

is revealing of Lewis’s thesis. Lewis’s novel gives flesh to these antipathetic positions. For instance, Jessup, a humanist who believes in Liberalism, is pitted against his son, Philip, who pragmatically adopts the tenets of Corpoism: we’ve got to base our future actions not on some desired Utopia but on what we really and truly have.

Ideology trumps humanity, and Jessup witnesses the age-old repression of a population in the name of higher ideals to return America to its former greatness. After all, Windrip has been aided to power through the effects of the Depression and the unresolved social inequalities suffered by many veterans of the Great War. These are the people to whom he must pander and offer hope, no matter how nebulous. As always, Jews and negroes are implicit enemies and suffer their political and social rights to be stripped away in Windrip’s fifteen-point plan. What Lewis could not foresee was that a representative of the political right could similarly tap into the hopes of the disaffected classes who suffered from the World Financial Crisis of 2008. Trump’s slogan – Make America Great Again – seems eerily paraphrased during Windrip’s campaign: To you and you only I look for help to make America a proud, rich land again.

At the same time, Lewis’s characterisation of political tyranny and freedom – as a struggle between tolerance and bigotry – rings true. One of Trump’s first acts as president was to ban people from Muslim countries entering America.

It Can’t Happen Here does not have the impact of big ideas like Nineteen Eighty-Four; it is not as conceptual. It is not as well-focused as The Handmaid’s Tale or Fahrenheit 451 in its depiction of tyranny through a single issue, nor does it imaginatively adapt the present into a possible future, as does Brave New World. But it has a compelling narrative which is also realistic enough to be disturbing. Alexander Hamilton and James Madison argued in The Federalist Papers that the American Constitution would protect its population from the weaknesses of human nature through the checks and balances between the three branches of government. Lewis speculates what might happen if those checks are removed: Congressional oversight upon the president, as happens to be the case here. Lewis’s novel may have had a satirical intention when it was published – a satire upon Roosevelt’s administration, perhaps – as well as sounding a note of warning about the allure of fascist ideologies: The way to stop crime,

Windrip asserts is to stop it!

Fascism tends to offer easy solutions to complex problems which are attractive, except for the reality behind the statement. But Doremus’s Liberal perspective continues to make this novel relevant to us – allows us as readers to set aside particular ideological positions and political affiliations – and focus upon the agency of tyranny, which lies in human nature rather than specific ideologies. Read in this way, the status of Lewis’s novel may well change in the future, and it may earn itself a place in the Dystopian canon.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!