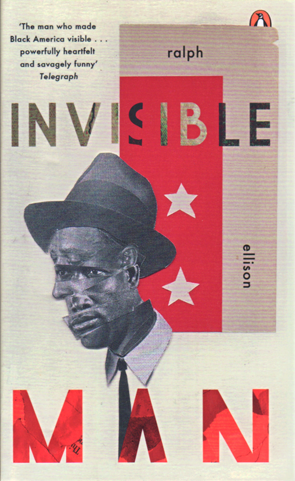

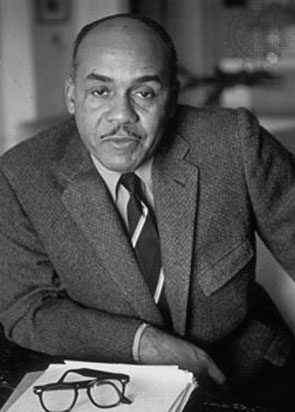

The Black Lives Matter movement which has received greater attention this year since the killing of George Floyd by police in May, might reasonably be assumed to be the impetus behind my reading Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man at this time. It’s true to a degree. When the protests started in America I remembered that I have intended to read this book since I watched Mission Impossible 3. And that’s where easy assumptions obviously end. The fact is, despite my belief that I had a fairly good knowledge of books, the existence of Ellison’s classic novel had somehow escaped my notice until I watched that movie. Laurence Fishburne, playing Theodore Brassel, describes their antagonist as an ‘invisible man’: “Wells, not Ellison” he clarifies. My interest was piqued. What was the difference? Somehow, despite my interest in books, this novel had remained essentially ‘invisible’ to me.

Unlike Wells’ character, Griffin, Ellison’s narrator – never named – clearly states in the prologue that “I am no spook”. He means he is not something from science fiction (“a piece of science fiction was the last thing I aspired to write” Ellison states in his introduction, written in 1981), rather than meaning the derogatory term once reserved for negroes. He is invisible he explains, “simply because people refuse to see me.” Invisibility is at the heart of his experience as a black man in America during the 1920s and 1930s. He suffers a kind of literal invisibility because he hides out underground in a cellar after being chased by police during a riot. His experiences have also given him a sense of invisibility, either because he is ignored by white society, or his sense of self is constantly shaped by his attempt to engage white society: to learn its values, to be accepted, to define his role in the world and to succeed.

Elllison’s novel is broadly picaresque in style, with the story progressing episodically from chapter to chapter. And this makes for a surprisingly engaging, entertaining and sometimes even funny novel. Some of the humour is somewhat disturbing, since we laugh at the absurdity of situations, even though we know what is portrayed is exploitative and racist. The first chapter after the prologue was published in Horizon magazine in 1947 and is an outrageous set piece that portrays the contempt with which young black men are held. The narrator, having spoken at his graduation ceremony, is invited to speak at a gathering of the town’s leading white citizens. Naturally he is filled with pride. The theme of his speech is “that humility was the secret, indeed, the very essence of progress.” The narrator explains that he has grown up believing he could define his identity through the expectations of others, and his speech is an expression of this belief. But when he attends the gathering, he finds that he is to fight – a ‘battle royal’ – with a group of other black men brought to the ballroom of a hotel for the amusement of the white leaders. He naively enters the melee, all the while thinking of his speech to be delivered once it is over. In fact, the white leaders do agree to hear him after the negro boys are forced to scramble for their payment upon an electrified mat. He speaks with a mouthful of blood, but he is given a scholarship for his troubles, and thus his naivety is rewarded.

But the narrator’s fate is not so fortuitous. He soon loses his place in the college after he is asked to drive Mr Norton, a college trustee, wherever he wishes to go. The events leading to the narrator’s expulsion are farcical, beginning with Norton’s curiosity to speak to a poor black man, Jim Trueblood, who has become a social pariah after accidentally impregnating his daughter while asleep. His family is so poor they can only afford one bed. Sickened by the encounter, Norton demands some whiskey to calm his nerves and insists on entering the Golden Day, a pub full of black people and mental patients on a day trip. Norton is knocked unconscious in a brawl and when the narrator returns him to the school, he is informed by Dr Bledsoe, the college’s head, that he no longer has a place in the college despite Norton’s assurances. Dr Bledsoe, himself a negro, is a duplicitous man who is proud of the power he has accumulated by conforming to the white man’s system. He sends the narrator to New York to get a job to earn enough money to return to the college, since he has now lost his scholarship. But the narrator is soon to discover that the letters of recommendation written by Bledsoe (not to be opened) warn Bledsoe’s contacts against him and state clearly that he will not be accepted back in the college.

This is only the set-up for the rest of the novel, which is largely concerned with the narrator’s life in Harlem and his attempts first to procure employment – he initially works in a paint factory – and his later involvement in the Brotherhood, a movement run by Brother Jack, a white man, that claims to seek equality for everyone in its community. The narrator’s oratorical skills are recognised by Brother Jack when he speaks against the police on behalf of a poor black couple who are being evicted from their home. He soon finds himself speaking at rallies and being indoctrinated into the ‘scientific’ methods employed by the Brotherhood to win over support for their cause.

It would be difficult and not desirable to draw together the many aspects of the plot of Invisible Man. What unifies Ellison’s story is the notion of invisibility and seeing, which is tied to black identity. Homer Barbee, the black orator who tells the story of the college’s founder like a story from the Bible, is blind to the shortcomings of Dr Bledsoe whom he endorses as the natural heir to the Leader, and is also literally blind. Brother Jack, who disapproves of the emotional appeal made by the narrator to his black constituents in Harlem, is blinded to the realities of his district by ideological belief. In a strange debating move he pops out a glass eye, revealing he is also partially blind. When the narrator is bumped into by a white man, he refrains from becoming angry because he knows the white man hasn’t seen him. He is invisible and unimportant to white society.

What is powerful in this novel is the way Ellison employs metaphors and symbols to dramatize the narrator’s situation. In the paint factory he is sent to the boiler room to work for Lucius Brockway, another black man who is not an engineer, but has been around so long he knows the boiler room and its processes better than anyone. He has helped develop the company’s bestselling paint, ‘Optic White’, and its slogan, “If it’s Optic White, It’s the Right White”, which the narrator intuitively associates with an old saying: “If you’re white, you’re right”. The message is clear. There is rightness to white society and something wrong with black society. The process by which the paint is made, incorporating dark elements into the mix of the paint only for it to paradoxically become an even brighter white, suggests the fate of black identity in a dominant white culture. Brockway has been paid a bonus for his efforts, but it is clear that while he idolises his employers he does not share in their wealth. He mostly works alone underground, separated from and despised by the union members whom he mistrusts, which anticipates the narrator’s situation underground later in the novel.

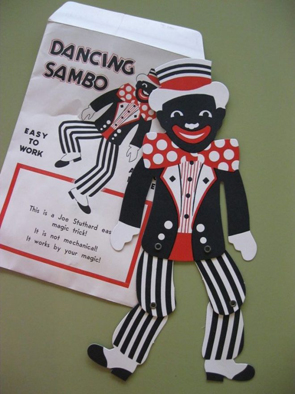

There are even more overtly racist symbols in the novel which are of interest. The narrator goes looking for a missing member of the Brotherhood, Tom Clifton, whom he finds on the street selling Sambo dolls. A crowd has gathered around, amused by the dancing movements of the doll. The doll represents the stereotype of the negro slave, lazy yet compliant. The narrator is shocked that Clifton, another black man, would stoop to selling the dolls, but when he realises how the doll is made to dance – a marionette puppet on strings – he begins to sense his own manipulation by the Brotherhood, which has a different political agenda to his own.

Another symbol is the negro bank which the narrator takes from his landlady’s residence:

It was a bank, a piece of early Americana, the kind of bank which, if a coin is placed in the hand and a lever pressed upon the back, will raise its arm and flip the coin into the grinning mouth.

He accidentally breaks the bank and finds it full of coins, then out of guilt at its destruction, takes it with him when he leaves the apartment. It’s coins, flowing out from its body, also recall the coins which he was made to wrestle other boys for after the battle royal.

There is tension in Ellison’s narrative between his narrator’s self-perception and the reality of black society. When the narrator dons a hat and sunglasses to disguise himself from Ras the Exhorter – a militant black man with his own supporters against the Brotherhood – he finds himself being constantly mistaken for another man, Rinehart. The narrator discovers through various false encounters, that Rinehart has embraced his own invisibility to the point that he has no true identity. To some he is a criminal organising illegal trades and bribes, while to others he is the Reverend Rinehart, a “spiritual theologist”, offering his acolytes the promise of the ‘invisible’ world of the spirit. Yet to the narrator ‘Rinehartism’ is a betrayal of the self and one’s place in history. He becomes intuitively aware that his own historical significance lies not in compliance with white society or to be measured by it, but in seeking an identity on his own terms. To that end there is something both ominous and promising in his self-imposed exile in the cellar as he waits to return to the world; something pregnant. The historical imperative is not for the narrator to adopt white characteristics – like components of Ultra White to be subsumed – but to help give birth to a pluralist America that embraces “many strands” in defiance of a winner-takes-all ideology.

Invisible Man is both a dense and complex novel that defies any attempt to fully draw together its various threads in a short summation. At the same time, it is a highly entertaining, fast-paced read. Sadly, the book might have been published this year rather than almost seventy years ago. When Tom Clifton is killed by the police after he sells his Sambo dolls illegally on the street, the consequences seem all-too-familiar.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!