It can be the subtle details that reveal so much about character and, consequently, of what a book like this is about. Mrs Pusey, holidaying at the Hotel du Lac in Sweden with her adult daughter, Jennifer, as she does each year, speaks to Edith Hope, the novel’s protagonist, about the debt she owes her daughter and late husband. I couldn’t do it,

she tells Edith, meaning that she couldn’t travel as she does at her age without her daughter. And she owes a great debt to her husband who provided such wealth before his death that she need never worry about money. Yes, well, I owed it to my husband,

she reminisces affectionately. He wouldn’t go anywhere without me. Said he couldn’t bear to be away from me, the silly man.

The subtlety lies in the reader remembering a minor detail 135 pages before this: …it became clear that Mr Pusey had frequently been left at home to do whatever he did while Jennifer and her mother took off for restorative trips to Cadenabbia or Lucerne or Amalfi or Deauville or Menton or Bordighera or Estoril.

We might smile at Mrs Pusey’s falsehood, but the fact is it details the wider problem of women’s relationship with men in this novel, and of equal consequence, of their relationship with one another.

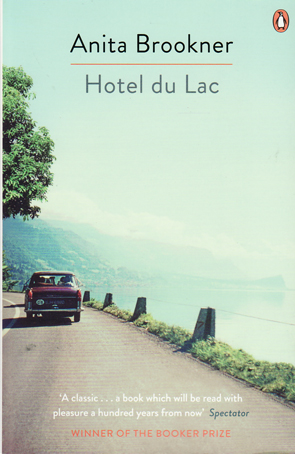

Edith Hope, a middle-aged writer of romantic fiction, has booked into the Swedish Hotel du Lac towards the end of its season, meaning the hotel is mostly bare except for Mrs Pusey and her adult daughter, Mme de Bonneuil, a woman cast off by her son whose wife has little regard for her, Monica, whose sojourn at the hotel is meant to revivify her health so that she might bear her husband’s children (or else!) and Mr Philip Neville, middle-aged and in search of a respectable wife. Such is the cast of Anita Brookner’s fourth novel.

Edith’s presence at the hotel is a kind of exile. She has become a social embarrassment after her behaviour in a recent relationship and her friends have urged her to take some time to reassess her life. Much of this novel is implicitly about Edith’s sexuality and her desire to find fulfilment in a relationship. She had been having an affair with David Simmonds for years, but far from feeling a sense of power in this relationship, she feels marginalised and defeated as she bears witness to David’s successful marriage and his successful wife, Priscilla. In fact, Edith sees herself as a tortoise

in a world of tortoises and hares.

Priscilla, Mrs Pusey and her daughter are hares; confident in their relationships with men and beneficiaries in the sexual stakes. Edith struggles to reconcile a new sexual etiquette with her own sexual desires. It’s sex for the young woman executive now, the Cosmopolitan reader, the girl with the executive briefcase,

Harold Webb, her literary agent, tells Edith. Edith’s books are quaint, tending towards being outdated, Harold implies. But Edith insists her novels have a place for those readers who are tortoises, not hares, with their identifiable heroine who is a mouse-like unassuming girl who gets the hero, while the scornful temptress with whom he has had a stormy affair retreats baffled from the fray, never to return.

Edith adds, In real life, of course, it is the hare who wins.

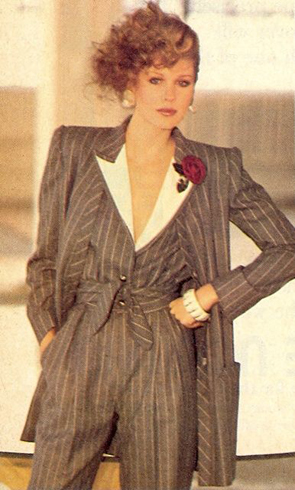

Complicating this perception is the fact that of all the women in the novel, Edith is the most independent, has juggled more than one relationship in the past few years and has not been without options. But Mrs Pusey’s presence at the hotel causes Edith to re-evaluate her understanding of women’s roles in the context of more aggressive and acquisitive feminism of the 1980s and the traditional marital roles assumed by many women, still. The question for Edith becomes one of what behaviour most becomes a woman

, caught as she is between the traditional marital role of women and the more aggressive feminism of female executives, intent on styling themselves along masculine lines, like the power suit with its imposing shoulders which was a thing in women’s executive fashion in the 1980s. But while the female executive might belong to the category of hares, so too can ultra-feminine

women who are consumers of men

; kept women like Mrs Pussy with their Treats. Indulgences. Privileges.

In essence, Edith seeks to negotiate a position somewhere between the traditional Madonna and whore

dichotomy which reduces women through a measure of their efficacy to men.

It is this social context that makes Hotel du Lac a powerful examination not only of sexual mores, but of Edith’s struggle to find her own place in this evolving sexual landscape, and not allow herself to be recruited

; to be made an accomplice

by the ultra-feminine likes of Mrs Pussy. When Philip Neville, a middle-aged business man, makes advances towards Edith, she must struggle with these questions, because what he offers is a chance to become a hare, but only at the cost of her more idealised notions love. Mr Neville is a fascinating character who appears little in the novel, but raises the narrative interest whenever he does appear. Infuriating, challenging and direct, he is neither a Mr Darcy or a Wickham.

The Times, according to the back cover of my copy, says the book is a smashing love story.

But it is not the kind of story Edith hope would have written for her tortoises, and there are more interesting things at play here between the other characters and Edith. I think the book offers a sophisticated portrayal of women’s relationships with men and with each other, and the problem of balance between social expectations and one’s obligation to oneself. An excellent book.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!