I’ve never read Anne Michaels before. She has an impressive writing resumé, having won “dozens of international awards, including the Orange Prize, the Guardian Fiction Prize, and the Lannan Award for Fiction” according to the Booker Prize website. That’s how I came to her novel, Held, since it has been shortlisted for the 2024 Booker Prize. Clearly, enough people have found this book worthy that any criticisms I make will be viewed by those who love it as narrow in scope, perhaps missing the point, even mean-minded. Held is a story about the loss of loved ones, of the felt presence of loved ones who have passed, about hope, about human connections, our sense of purpose or fate, and about a sense of our wider place in the world and what might be possible just beyond humanity’s mechanisms to understand it. Good novels often encourage this kind of reflection. But as I started reading Held, I was also aware that it had received both positive and negative reactions from book vloggers and in reviews on Goodreads. Polarising books can be interesting and I was interested in why this book had such a range of reactions with the public. Some loved the language and sentiments of the novel, others thought it pretentious, opaque, overwritten and/or confused. For my own part, I enjoyed aspects of the broad story, particularly the generational story that is mainly centred on John and Helena, as well as their daughter, Anna (mostly an absence in the story), her husband, Peter, and their daughter, Mara. This is a novel about people, but first and foremost, I felt as I read, it is a novel about an idea, as many are. But unlike many great novels which allow the reader space to ponder and reflect, Held felt like an act of proselytising. It’s a thesis dressed up in people’s clothing, walking and talking, with a determined purpose. This is an aspect of the book I disliked, yet I have found that others have been drawn to it. Held was different for me. It felt like a manipulative book. It felt dishonest.

One aspect of the novel that has received criticism from readers – an aspect that didn’t bother me – was the novel’s non-linear narrative, its lack of traditional narrative progressions and a clear overall plot. If that kind of thing bothers you, this may not be the book for you. Held is written in twelve parts. It starts on a battleground in France in 1917. Each part sees a shift in the novel’s time setting, often changing its location and characters, also, so that readers have to pay attention to the connections between different parts of the story and its characters. Some readers claim they have difficulty following the connections between characters from one part to another, while many more seem to see no connection between the last parts of the book and the rest of the story, at all. When I first wrote this review, I also got some connections between minor characters incorrect, and it took comments from readers to alert me to this. For this reason, I have produced a revised character map with a list of the story parts, the main aspects of the plot in each of those parts, and I list which characters appear. You can view or download this as a PDF file by clicking on the links, below:

The character map is probably more useful after reading, and the overview provided on the right-hand side of the page will only make sense if you’ve read the book. It had to be succinct.

The novel begins with John, wounded on a battlefield in France, his friend, Gillies, dead nearby. As John lays there he thinks of his wife, Helena, and how they seemed to meet by chance one night at an inn. The story follows John and Helena for a while with what is a fairly conventional narrative. John returns from war with an injured leg. He is a photographer. He and Helena live over his photography studio. John hires an assistant, Robert Stanley, who does not appear to be all he says. He cannot provide proof that he was in the war. He seems secretive. His politics are different to John’s. Nevertheless, John and Mr Stanley form a workable relationship until the picture of a young soldier, who John has photographed in uniform for the boy’s father, is developed. The image features an older woman next to the young soldier. She was not present in the studio when the photograph was taken. When shown the photograph, the young soldier identifies the woman as his dead mother.

By this stage I had been getting into the narrative well enough, and this development further piqued my interest. This was a story about grief and loss. John had lost his friend on the battlefield, Helena had lost her parents before she even married John, and now this soldier is revealed to have this absence in his life, also. Mr Stanley sees commercial potential in this miraculous occurrence. John is more circumspect, understanding the event as an act of Grace he cannot control and should not exploit. Then it is revealed that the reason Mr Stanley feels wrong to us is because he is a fake. He has not fought in the war as he claimed and he has lost no-one. He is not trustworthy. He steals John’s equipment, arrogantly believing he can take control of something beyond his understanding and make money from it. Our sympathies lie with John and the soldier.

The appearance of the dead mother in the photograph feels like a familiar fictional trope: of the impossible happening within the bounds of realism – otherwise known as Magic Realism – which helps elucidate a story or characterise a situation. Like the doors which magically appear across the world in Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West: as a practical matter, they break down the barriers of movement, of immigration, and circumvent restrictions placed on refugees. As a thematic device, Hamid’s doors help us question the traditional divisions of humanity by race, culture and nationality. So, I was actually interested to see how this idea of the dead reappearing in Held developed (pun intended).

As the story moves into the next generation, we are introduced to Peter who has married Anna, John and Helena’s daughter. Anna, however, has already died. She is an absence in this novel. She is mostly only referred to; rarely occupying the stage. Now, Peter frets about their daughter, Mara, who places herself in danger by working in third world countries and war zones. From here the story expands ever outwards in time, across generations and different character groups, all of whom are connected in some way, however tenuously.

Yet, as I read, I was increasingly of the opinion that the characters and their stories are secondary to an idea and belief system that it is the author’s intention to promote. For me, it was difficult to separate the narrative voice or thematic concerns of the novel from the actual voice of the author, something a reader would normally do. Mr Collins does not speak for Jane Austen, for instance, but this felt more like Howard Roark’s speech in The Fountainhead emerging directly from the mind of Ayn Rand: a manifesto in that case, rather than a character speaking.

I’m aware I’m going to use words like ‘spiritualism’ and ‘mysticism’ interchangeably here, when I know there are differences of meaning between them. What I mean is that Michaels’ novel seems to have been written to promote the idea of a mystical world: a world beyond our senses; a world of the spirit, or soul, which someone with a heightened perception, someone like a spiritualist, might access. These are not my beliefs, but I’m fine with them in fiction. That's not the basis of my reaction to the novel. My response has to do with the way Michaels communicates with the reader and uses her power as an author. She has a skilled control of language which is on display throughout, but I feel she manipulates and is openly dishonest with her reader. I hope what follows makes sense of that.

Held is not only divided into twelve parts, but is sectioned into vignettes and short insights, which make for a quick read. It also allows Michaels to interweave philosophical musings and aphoristic statements into the story, and these become predominantly important. They are highly appealing. Wisdom distilled into a sentence is memorable, repeatable, learnable. And Michaels’ poetic background is on display, with sentences, euphonic and crafted, that appeal to the senses, containing binary and dualistic arguments that appear to offer simple and logical choices or easy insights. Consider the opening sentences of the novel:

We know life is finite. Why should we believe that death lasts forever?

In these two short sentences, Michaels moves from a simple fact to a rhetorical strategy. These paired senses create a false equivalence: by equating life/death, the second pairing, finite/forever, appears irrational. This logic is subtly reinforced in the next sentence:

The shadow of a bird moved across the hill; he could not see the bird.

It is one sentence, but the structure is the same. Michaels begins with a simple fact – what is known – and progresses the scene to a place that is unknown: “he could not see the bird.” The bird has moved beyond John’s sight, but it is ludicrous to expect, as a child yet to develop object permanence might, that the bird no longer exists. By the use of analogy Michaels forces her reader to address an implicit question: what can we really know about the state of death once someone has moved beyond life? I have to admit, this is very clever writing. Reading the novel is like a frog being slowly boiled. Michaels’ rhetorical strategies are insistent and incremental.

The stories about the novel’s characters span from as late as 2025 to as early as 1910, when Lia, Peter’s mother, meets a photographer in the woods. Their discussion encapsulates many of the themes of the novel in the typically elevated discourse found in philosophical fiction, with the stark contrast made between the lives of the mating mayflies they observe, juxtaposed with the tremendous timescales of their species’ existence – over 350 million years old - “yet with a female lifespan of five minutes and a male, two days.” Michaels typically inserts facts like this into her narrative. Beside the mating of the mayflies, the enormous scale of time and of the earth is even more staggering, with Nature’s processes of continental drift, erosion, meteor shocks and evolution providing a counter-narrative that pales human experience into insignificance:

The flow of ice growing like stillness. The frozen torrent pushing and pulverising, carrying and crushing, prying and dislodging, picking up and setting down, slow violence and its own slow repair – the wide valleys, the sweet grasses of the upper pastures, rivers settling into their beds. In the expanse of the ice, polynya opening like a wound or a well. The weight of the ice shifting like a sea. Glaciers moaning in the darkness.

The landscape is eroticised with a series of verbs that suggest sexual coupling – “crushing, prying and dislodging”, as well erotic zones – “wide valleys”, “rivers settling into their beds”, “opening like a wound” and glaciers “moaning”, that dwarf human experience and understanding.

Against the drama of these vast time scales the presence – or evidence of – any one individual would be infinitesimal. When John first makes love to Helena on their marriage night he is struck by this same insight:

He did not expect to feel this, that he had become part of the human story, the countless who had lain together for the first time, who so easily might never have met, this magnitude they’d discovered that was only an emanation of blind chance – blind chance an argument for destiny he had never considered before.

John’s overwhelming feeling, that his life might have been anything other than what it is, is a logical response to the sense of the insignificance he feels. This is foundational to the argument Michaels is developing about science and mysticism. Mysticism, a convenient word here I use to mean the world beyond our lived experience, is beyond the understanding of our quotidian existence and the ken of science:

… meaning lies beyond the reach and intent of science. Science can never determine if there is something beyond flesh and bone because that inquiry is inadmissible.

A reality beyond the senses is beyond the purview of science, mired in observation and testing. It is true that science cannot explain everything. But Michaels chooses to load the argument both ways, using science to also legitimate her position: that life is infinite; that our ability to perceive the full gamut of reality, which includes the world beyond what we understand as life, has so far been limited by our own evolution.

The slow evolution of perception: the first vertebrates to move from water to land, beginning to grow what would become eardrums, detecting low frequencies as vibrations in their heads … When we grew eyes did others of our kind believe us mad for what we saw?

This is why photography is so important in this novel. Beyond the miraculous photo of the dead woman and her soldier son, its importance lies in the fact that cameras of various kinds are machines of science, capable of recording more than our eyes can see: the mundane details, but also through the agency of discoveries like x-rays and gamma rays. The soldier’s photograph reveals his mother’s spirit revealed; the invisible made visible. In a letter to Ernest Rutherford, the scientist who discovered Gamma rays and produced a model of the atom, John tries to explain the mystical phenomena of the photograph in a manner that seems to anticipate Louis-Victor de Broglie’s theory of wave-particle duality, introduced four years after John’s letter, in reality. Broglie discovered that light was both particles and waves. The model John attempts to explain seems to be based upon this idea. John imagines the photographic plate as “a surface where time and space meet.” He further explains that our existence is defined by time and space: “A particle exists in space, a wave exists in time” he asserts, “so the observed electron will always behave like both particle and wave. ” John/Michaels uses the language of science to establish or explain the miraculous photograph, but the explanation becomes confused and the sense of it founders. It becomes unclear how the particle reacts with the photographic surface while at the same time is a product of our movement and choices in the world. The particle and the wave create a conscience, John explains, but that seems to encompass both a literal memory as well as some kind of pseudo-scientific/mystical force. And once the logic is mired in this conundrum the argument retreats to a common strategy used in the novel, the rhetorical question: “Why would it not be possible for the glass plate to capture what the eye cannot?” Why, indeed? This is a metaphor that steps beyond fiction; that Michaels struggles to make a reality.

The metaphorical potential of photography is used more successfully in the example of time-lapse photography taken of cities by Lia’s photographer. What is revealed is the scale of time itself: first, through the various photographs that reveal the changes in the city which would now otherwise only remain in memory. But the elision of humanity from the photographs suggests also our insignificance in the grander scale of the world, as we saw in the evolving world of insects. Lia asks the photographer why there are no people in his city scapes. He explains: “If you open the shutter long enough, everything moving disappears.” It’s a neat and humbling metaphor for our own insignificance. But it is also a metaphor for the possibility of a mystical reality beyond our sight and understanding: that a photographic plate can reveal emptiness, also, where in reality, “it would be full of life, invisible and real.” In these photographs, we are the reality the camera cannot see.

Michaels references science and scientists throughout the novel. Science is both detracted and held as an authority, according to purpose. When Michaels wishes to diminish science, she speaks of the “avarice of science, its conflation of knowledge and control”; that science “must never foreclose what it does not understand.” And she pokes science with its own logic: “if observation changes the phenomenon, how can we know anything?” At other times science is the authority for a universe predicated upon order and purpose. But science’s natural antagonism towards the supernatural, Michaels asserts (or Paavo, one of her characters, thinks (but her characters increasingly become merely ciphers for her arguments)) will paradoxically, in the end, make sense of the ineffable world beyond the senses “only because science is bent on proving it doesn’t exist.”

The paradox of the empty city in the photograph is one example. But Michaels also progresses this argument through a series of observations about liminality, that uncertain place between two things or states. First, she introduces examples we can understand and easily accept as part of the ordinary experience of living. For example, the difficulty of defining the exact moment when night falls, or when we fall asleep. Next, she asks a question naturally predicated upon this thought: is dying like night falling, and therefore, implicitly, like sleep. Compare this to John’s memory of Gillies, dead on the battleground who looks “absolutely, utterly awake.” Michael’s is breaking down the barrier we perceive between life and death. For instance, there is the incredible moment of a child’s birth to consider as well; that moment between non-existence (in our experience of a newborn child) and its sudden emergence into our perception. Another example, the gap between the wick of a candle and its flame, becomes an exemplar of that liminal space in which two states are linked by the invisible: between the body and the soul. What is known and unknown, can be expressed in the boundaries of “a bare micrometre.”

The overwhelming impression is that this is polemical discourse parading as a novel. For instance, Astartine, we learn through the elevated conversation of Michaels’ philosophical characters, is an element that virtually does not exist, except for about a second as uranium decays. Astartine is that bird flying over the hill beyond our sight: an element that does not exist, except that it does. What is absent is also real. By the use of this scientific metaphor a mystical reality is asserted.

Michaels uses the logic she has established around liminality to progress her arguments. What is beyond the body is the world and the world only exists to us within the parameters of our senses. The argument in the novel is not subtle:

How can we doubt the existence of what is invisible? How can we conflate invisibility with inexistence?

Presences and absence are therefore important in the novel. As readers we feel Anna’s absence throughout the story even though, if you follow the structure of the character map, she seems to be a pivotal character connecting the various character groups. Absences become significant in key moments of intuition. “There are so many ways the dead show us they are with us” we are told early in the novel. This thought is later expanded: “Everywhere the dead are leaving a sign. We feel the shadow but cannot see what casts the shadow.” Later, the unnamed narrator of part nine reflects upon her epiphany, that her dead husband is present:

It must have been unbearable to be pressed against the air, hearing me shouting for you, not being able to answer. Neither of us fluent then in the language of the dead. But now, my ears and eyes never miss a sign you send me: a flicker of light between the trees, a twitch of wind across my face, a bird sitting for long minutes on a branch beside me, unafraid.

Michaels steps beyond the usual boundary between writer and narrator in order to manipulate and convince the reader of her thesis. The novel’s intention, it seems, is to pry open a mental door closed against these ideas, and then to stick a shoe in the gap to keep it from shutting; the classic strategy of the archetypal door-to-door salesman. This criticism doesn’t reside with a belief about mysticism, but with Michaels’ strategies within the novel, itself.

A response to my arguments, so far, may be that I am engaging in a form of pedantry and nit-picking: that this is fiction and things that can’t happen, happen in fiction. This is true. But there is a difference in a fantasy world, for instance, in which the rules have been determined by the author. Where magic exists. Fine. Gods or ghosts exist? Fine. Or in Magical Realism, where the impossible is often a metaphor for reality. Or even fictional texts like The Lovely Bones or The Water Babies where there exists life after death. Fine.

But Michaels’ inferred intention is to step beyond this and convince us. She misrepresents science and she misrepresents the truth to argue for a reality that is otherwise unsupported by the facts she draws to her, or asserts. Foremost, for me, is an abuse of the author/reader relationship. The word ‘author’ is a root for ‘authority’, meaning that we tend to trust what authors have to say; there is a disproportionate power relationship between reader and author. Authors have done their research, we believe. They are knowledgeable about topics that they or their characters discuss, and this is supported by a publishing industry that has invested in the author and their book, and a culture that elevates their work.

But the interests of Michaels’ novel rests with a dialectical tension between science and mysticism; between the visible and invisible worlds; between rationalism and belief. Michaels’ use of rhetorical strategies – questions, paradoxes, metaphors and the use of science’s authority – is part of this. But she also makes misrepresentations to the reader for persuasive purposes, too.

The last few sections of this novel – the part some readers say they have had trouble linking to the rest of the narrative – digresses to tell the story of Marie Curie, a newly-minted doctor of science. It is 1908 and Marie Curie is attending a dinner held in her honour. Ernest Rutherford is present. One of the curiosities of Marie Curie’s story which Michaels has found apropos to her purpose, is the interest she and her husband, Pierre, had in spiritualism. It is not so surprising if you consider that there was a desire to observe and test phenomena displayed by spiritualists and mystics early last century. Observation and testing are part of the scientific process. It is the same curiosity and open-mindedness that led Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, to believe in fairies. The instrument used to fool him, ironically, was a camera and the trick photography of two young girls.

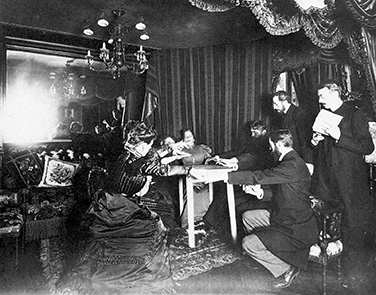

In part nine, when we are first introduced to Marie Curie’s story, Michaels recounts the story of Madame Palladino, a famous mystic of the period. Marie and Pierre Curie attended séances held by Madama Palladino for the purposes of scientific study. The account of Palladino’s purported powers comes late in the novel, and feels like it is meant to be a climactic summation and demonstration of Michaels’ thesis:

At the séances of Madame Palladino, the investigating scientists had bound the medium’s arms and held her hands, they pressed down on her feet with their own, they insisted the room remain light enough to scrutinise her every movement. Pierre Curie described how they had measured the muscle contractions of her limbs with sensitive instruments while objects flew about the room: they monitored acoustical vibrations, electrical and magnetic fields; they used electroscopes and compasses and galvanometers to analyse objects moving at a distance – yet still Madame Palladino held the very air with her powers, and the table rose, and an invisible force parted the curtains, and no one, not all the intelligence of l’Académie, could detect deception.

The assertion made in the final sentence recalls Paavo’s belief that science will prove the tenets of mysticism by trying to disprove it, a thought placed in the reader’s mind only ten pages before this. This passage is possibly the most objective example of Michaels’ deceptiveness. The story of Madame Palladino, seemingly validated by famous scientists through a scientific process, is a cherry-picked and inaccurate account.

The Curies were interested in whether mystical phenomena had a link to radioactivity. Pierre Curie, who was more interested in Palladino than Marie, wrote:

… the only trick possible is that which could result from an extraordinary facility of the medium as a magician. But how do you explain the phenomena when one is holding her hands and feet and when the light is sufficient so that one can see everything that happens?

Pierre Curie was inclined to believe in Palladino. However, this does not give Palladino’s tricks the imprimatur of scientific veracity, as seems implied by the use of the story, here, by Michaels. Pierre Curie was a fallible man, like anyone else, and was entitled to his opinion. Even so, the final report written by the commission investigating Madame Palladino, of which the Curies were a part, described Palladino as a “detestable” subject whose lack of cooperation had made rigorous controls impossible, and stated that she had often been caught cheating. This was a story repeated throughout her career. Palladino was often exposed as a fraud. But facts mean little when belief is involved, and Madame Palladino maintained her believers, even though scientific papers and a book would be published outlining exactly how she achieved her illusions. Even over a century later, Michaels has used a version of her story to make her own case. Yet, later in her career Palladino even admitted that she was not genuine. If you are interested to read about this, there is an article I read on Wikipedia about Palladino as well as a longer piece published by Cambridge University Press, which gives far more detail about this subject than I can give here.

This is my problem with this book. I would be fine with a novel that offers comfort in the thought of loved ones speaking from beyond the grave. Isn’t that what the movie Ghost is about? Isn’t the idea of life beyond death the premise of many horror films? And didn’t we laugh along with the idea when we watched Ghostbusters? But Anne Michael’s story goes beyond fictional indulgence. She misrepresents science and she misrepresents the truth of an experiment and the known history of a fraudster to bolster a thesis. It feels anti-intellectual. Our world is full enough with the mistrust of science, knowledge and facts. Yet Anne Michaels progresses her argument on the presumption that a negative or absence is proof of a positive. After all, science can’t disprove it: “if observation changes the phenomenon, how can we know anything?”

I think Held fails in its purpose – I think its foremost purpose is to persuade – because it is intellectually dishonest. But this failure is only evident with knowledge or a determination to check facts. Without that, the novel may seem insightful, even profound. I can imagine myself having enjoyed this novel had it not been written with such a determined undertaking. But the trick of an illusionist is to make you believe you have seen something you have not and I felt that this book is like the trick of an illusionist. I found the authorial voice so distinct and unrelenting in its purpose that it was intrusive. The narrative uses rhetorical techniques to manipulate its reader, it misrepresents scientific fact and historic fact, and like its poster child for spiritualism, Eusapia Palladino, it is fraudulent because of its methods. That’s the time when you hear something else from readers about books: that they didn’t understand it, or weren’t smart enough for it: “I wish I was more intelligent so I could understand everything in the book. I'm just normal but I felt inspired as I read” [Goodreads]. Readers often believe a book is too good for them when it makes them feel like this. That’s not where readers should be left. Not with a book like this.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!