I guess one of the things to ask when reading Dystopian fiction is what has this book has got to offer that is new? In the case of Hazards of Time Travel, the answer is that it is not an original book. Its world is reminiscent of Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. Adriane Strohl, the novel’s protagonist, is convicted of a crime and Exiled in an early scene. Her fellow students are asked to ratify Adriane’s Exile with a vote, recalling hate week in Nineteen Eighty-Four, an expression of mass-thinking, or the ‘salvaging’ that makes complicit the handmaidens in the ideology of oppression in Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale when they are used to kill a man. In both those instances the individual’s own moral code is subverted by terror; by instilling fear in the power of the State. So, this book addresses issues that have been the subject of previous Dystopian / Science Fiction novels: upon what basis is the Social Contract made? for instance. And to what extent are we autonomous? (which is akin to the old chestnut about defining our humanity: what is it that makes us human?) These are broader considerations which reflect our own social and historical context; specifically, the erosion of personal and political freedoms in a post-9/11 world. This is an abstract concern which Oates attempts to tease out in a narrative that also tries to engage us emotionally.

Adriane Strohl is the valedictorian student at Pennsboro High School, set in the near future in a country known as the NAS, the North American States, occupying territory formerly known as the United States of America. Adriane has played a dangerous game with her education. Rather than remaining middling, she has recklessly outshone her classmates in a world in which intellectual curiosity and the ability to question authority have increasingly come under suspicion. Dissenters, provocateurs and activists all risk various levels of repression, from being labelled a Marked Individual (MI), thereby destroying their reputations and careers (a fate that has befallen Adriane’s father), to being vaporised by a drone strike – a quick death – or being Deleted, meaning not only death, but the destruction of all records of their existence, including all family effects like personal records and photographs, and the banning of their friends and family from ever speaking of them again. Like Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, surveillance is all-pervasive. Adriane’s uncle Tobias was deleted when she was only two years old. She only knows of him because her father has managed to hide a few photographs in their attic from the authorities.

There is another form of punishment: Exile. Exile is like a prison term, except that the individual is tele-transported into the past, to the days before the computer revolution, there to serve a fixed sentence under strict rules before they might join their families again in their present time. This is the fate of Adriane. Having used her valedictory speech to ask forbidden questions, she is arrested and sentenced. Her ‘prison cell’ is the campus of Acrady College, 1959 – otherwise known as Zone 9 – circumscribed by a ten-mile radius within which she is allowed to move. Her new identity is ‘Mary Ellen Enright’. She is forbidden to reveal any knowledge of the future or even hint at her true identity to members of this world.

The crux of Adriane’s story lies in how the self is formed: whether there is an essential self within or whether the self is an automated machine reacting to its environment. Initially, this would appear to frame a religious versus a scientific understanding of the self. Adriane states that her parents were loving parents

who taught There is a soul within. There is ‘free will’ within.

Yet their advice is wholly secular, given to her in the context of a repressive political system: the State is lacking a soul, and there is no ‘free will’ that you can see. Trust the inner, not the outer. Trust the soul, not the State.

The twelve questions asked by Adriane in her valedictory speech (a number with religious overtones again) are subversive not because they challenge the state apparatus directly, but because they fall outside the ideological and historical construct of the State: What came before the beginning of time?

and What came before the Great Terrorists Attacks of 9/11?

Time is now measured from the 9/11 attacks, suggesting first, that everything that came before is irrelevant, and second, that the attacks were the catalyst for everything the world has become: that American culture was warped by this event and all that subsequently happened.

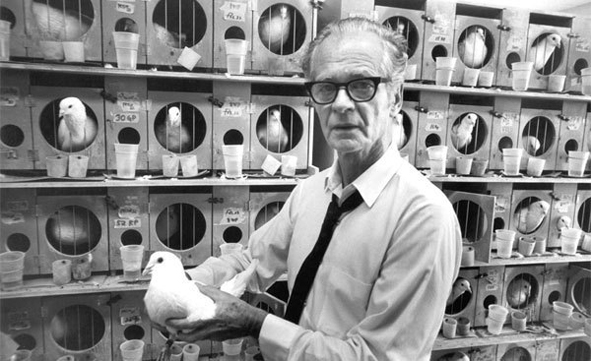

I think Oates’s intention in this novel rests not upon advocating a spiritual life – Adriane rejects this – but a belief in curiosity, knowledge and informed choices as fundamentals of our humanity. This forms much of the basis of the plot. Adriane/Mary is enrolled in a psychology degree under the mentorship of Professor A.J.Axel and his assistant, Ira Wolfman. Axel is a behavioural psychologist who follows the behavioural theories of B.F.Skinner, that an animal is essentially a machine reacting to its environment. It’s a theoretical position clearly at odds with Adriane/Mary’s belief in her inner-self which she must at once try to preserve but at the same time repress if she is to survive in 1959. But Axel’s teachings call into question a belief in an essential self. This is illustrated by the obvious metaphor of rats in a maze – have they little will to resist running the maze for the reward, or are they driven by their own will, given the constraints of their environment? Moreover, to what extent can an essential self be maintained within a deleterious situation? The metaphor applies to the self, but it is easily widened to apply to the challenges of political oppression against the self, and further still, to the challenges to social ideals in the face of repression and challenges to laws that are based upon Enlightenment thinking. In 1959 – indeed, prior to that, during the McCarthy trials which are referenced in the novel –threats against the individual in order to maintain wider social ‘norms’ was evident. Attempts to ‘cure’ homosexuality (Axel’s studies, in part, drive towards this end), and widening again to attempts to mould political thought, begin at the level of the individual and one’s sense of identity: Already in 1959 … it had become a technique to discredit ‘rebellious’ individuals by suggesting that they were mentally ill – emotionally unstable.

I think this is an insightful novel that shares some philosophical ideals with Oates’s previous book, A Book of American Martyrs, even though their subject matter and tone are widely at variance. A Book of American Martyrs deals with the question of abortion in America, and packs an incredible emotional as well as intellectual punch, while also giving voice to both sides of the debate. In essence, though, it is also about the individual’s compact with the state. Yet, while Hazards of Time Travel also explores issues of the individual and the state with great skill, I think it is a lesser novel than its predecessor in that it fails to engage as convincingly on the human level. Oates does not take as much time to build Adriane’s world prior to her Exile, and we know much less about her family than we come to know about the families of Luther Dunphy or Dr Gus Vorhees in A Book of American Martyrs. The opening of the novel lacks the impact of the previous book, too. Instead of drama, Oates has chosen, instead, to steep us in the oppressive language of the NAS to begin with – the so-called Instructions under which an Exile must live – so it’s a tougher ask for a reader to initially engage. But added to this is the relationship that develops slowly between Adriane and her tutor, Ira Wolfman. Adriane is drawn to Wolfman because she believes him to be another Exile, but apart from her many assertions of desire for him, it is never quite clear what draws her to him in the first place, or what the nature of their relationship truly is. This is not a fault in the storytelling, since these aspects of their relationship are essential to the novel, but it is a colder and less engaging novel, nevertheless.

The strength of the novel lies in the tension between opposing notions of the self, and this is played out in its denouement, which leaves the reader to contemplate their own assumptions of the story’s premise. There is a certain level of correlation between an unwitting character, a rat in a maze and the reader who must negotiate the plot. Adriane decides that Life is not thinking, not reflective or backward-glancing; life is forward-plunging.

One is left to wonder, that if a rat was able to form such a thought as it ran through a maze, whether this optimistic assertion could be accepted by an independent observer aware of a wider world and the context under which the rat runs. It’s an eerie thought as we close the novel, whether we ourselves in our post-9/11 world are forward-plunging, or whether the impetus of history draws us inexorably to a different world in the future, based upon reactions barely understood, to events we hardly control. Wolfman, who has future knowledge like Adriane, points out that Acrady College is an intellectual backwater, with professors punishing innovation and backing soon-to-be outmoded theories. In the same way, how do we know what we think now is the right ideological or theoretical construct to follow? How is it possible to confidently build a future, or to trust those who are assigned to direct that future?

Hazards of Time Travel is a thought-provoking novel, if not as gripping as Oates’s previous novel, A Book of American Martyrs. However, whatever reservations I seem to make in this review about Hazards of Time Travel through comparisons to other books, this is an excellent book, nonetheless, and I would encourage people to read it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!