Ghost Empire is a hybrid book, part history, part travelogue. The book is loosely based upon Richard Fidler’s journey to Istanbul when his son, Joe, was fourteen. Fidler explains how he has instilled a love of history in his son and wants him to know the story of Constantinople, of its rise, of its cultural and military power as the eastern arm of the Roman empire, and then its demise until its eventual overthrow by the Ottoman Turks in 1453, when it was renamed Istanbul. Constantinople’s power spanned over a thousand years, so Fidler has a lot of ground to and many interesting stories from which to draw.

I learned a lot from reading the book. The story of Constantinople is one that was long neglected by historians and was certainly not part of my school or university curriculum. With that said, the book is really an introductory work, suitable for the general reader, not a scholarly text. But that’s not what it is trying to be. Is does have endnotes, a bibliography and an index – all the things you might expect from a book of history. But the book is as much a personal meditation upon the past, as well as a piece of travel writing. With Ghost Empire, what the reader has is a series of interesting stories that give a broad overview, but not an in-depth account. This is actually the strength of the book.

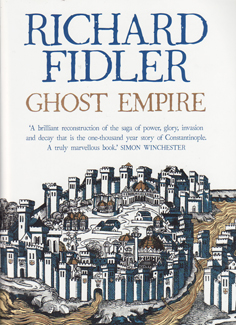

The text is broken into small sections, which makes it highly readable. There is never more than a page to a page and a half of writing without some kind of break or heading. The text is also interspersed with some pictures, both from historical sources as well as Fidler’s own photographs. I found this to be one aspect of the book that could have been improved. Fidler’s newest book, Saga Land, based on Iceland, its history and legends, incorporates larger pictures, some of which are in colour. I thought a book of this kind needed more illustrations and pictures. They needed to be larger and clearer. After all, Istanbul is a city many readers will never get to see. The pictures would have helped to bring this story to life even more.

Fidler’s travelogue is also patchy. There are some aspects of it that help the reader to understand what has happened to the city that was once Constantinople. For instance, Fidler and his son walk the length of the Theodosian Walls, now in ruins, often treated with contempt or indifference by the modern city. Fidler identifies the Golden Gate, where emperors once entered the city in procession (again, a better picture would have been nice) and he considers the size of the army led by Mehmed, that was large enough to span the entire length of the walls which take Fidler and his son an entire day to walk. Or he speculates that the palladium, a small wooden statue once buried under Constantine’s Column, said to have originated in Troy and to have resided in Rome, might still be there. The thought is tantalising.

However, I didn’t feel the travelogue always provided as compelling a gateway to the historical narrative as much as it might. Each new corner, building or experience Fidler relates of Istanbul should be an opening doorway to the past. He usually achieves this, like when he visits the Hagia Sophia, once Christendom’s greatest church, now a mosque. Or the story of the immovable ladder that had been sitting on a ledge of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre for two hundred years. The Ottomans, trying to broker peace between religious factions, had established a rule that nothing could be done to the church without the agreement of all six priests. So, when someone left a ladder there, it couldn’t be moved because no one of the six priests could agree to have it moved. It’s a nice vignette of the intransigence that is sometimes the result of stalwart religious positions. Nothing much has changed over the centuries, Fidler implies.

But his personal journey sometimes feels like an adjunct to the main story. As a travelling companion, Fidler isn’t as interesting as Bill Bryson, for instance. Bryson has an ability to make you feel like a kid again, sat upon the lap of a charismatic grandfather, or in the company of some clever raconteur at the pub, wanting to know the story behind the story. Fidler doesn’t have the same charm as Bryson, even if his subject is very interesting and his account is good.

In reality, this is a small criticism. Because, how could you go wrong with a story like Constantinople? It’s just too good. I personally found the historical narrative the strongest aspect of the book, which also forms the vast majority of the text. Fidler begins with the reigns of Constantine and Justinian. Of particular interest to me was the story of Constantine’s adoption of Christianity and the Nicaean Council in which the key tenets of Christianity were set in cement. It’s a good reminder that Christianity was adopted for political reasons and that many of its key beliefs, particularly concerning the Trinity, were argued over and never entirely resolved; that they were political compromises. Yet Fidler tries to remain on the respectful side of the religious debate, declaring his cards by saying he is an atheist, although burning Richard Dawkins in an attempt to moderate his own position. He claims Richard Dawkins has no respect for the culture or art of religion, thereby suggesting that Dawkins is an extremist who is blinded by science to the potential of beauty. I wondered about Fidler position, since I have seen several videos of Dawkins proclaiming exactly the opposite. But I understood what he was trying to do. He was trying to give Constantinople and its culture due deference.

The most interesting aspects of the historical arc, for me, lay in the story of the Fourth Crusade which set the stage for the eventual fall of Constantinople. I remember studying a little about the Crusades in junior high school. I think we focussed mostly on the first, since the Christians made ground in that attempt to seize the Holy Land back from Muslim control. We learned less about the Second and Third Crusades. When I heard of a Fourth Crusade I asked the teacher about it, but was told that the fourth was of little importance. Well, true, if you consider its significance in the attempt to take back Jerusalem. The crusaders never got to Jerusalem. But what a great story! Beginning with Pope Innocent calling for another crusade to take Jerusalem, it is the story of a terrible cock-up. The Venetians enter into an agreement with crusaders to supply a fleet for which they will be paid. But a year later when the armies are meant to gather, there are fewer crusaders than expected. The debt to the Venetians can’t be paid. The Venetians hit upon a plan to reinstall Alexius Angelus, son of Emperor Isaac, who had been overthrown by his brother. In return, the crusaders will be rewarded by Alexius from the treasury of Constantinople, from which they can repay the Venetians. The people will open the gates to their true emperor, the Venetians argue, hoping to quell misgivings from crusader armies about attacking a Christian city. Funnily enough, this doesn’t happen. When Alexius is presented on a boat to the people of Constantinople, standing on the walls of the city, they throw cabbages instead. The eventual invasion of the city sees the inhabitants flee and set up governments in exile, the treasury plundered and the whole purpose of the Fourth Crusade fall apart. The crusaders never make it to Jerusalem to defend Christendom. Instead, they tear apart the greatest city of Christendom, the bulwark of Christianity against the Moslem east, and set the scene for the slow decline of Constantinople, leading to its downfall. Irony does not get any more pointed than that.

Over all, Fidler’s book is highly readable, entertaining and informative for someone like myself who is unfamiliar with much of the history. I think Fidler manages to give a sense of the significance of the events he retells, both in their historical context and to the modern world. I might note that I am writing this review in the week when Donald Trump has recognised Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. Already there has been violence. Despite some of the book’s minor weaknesses, it makes this old story come alive for modern readers and reminds us that history is always relevant. This is an enjoyable read and highly recommended.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!