Fleishman is in Trouble is Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s first novel, and she has proved herself to be an astounding writer. Not that she has come from nowhere to produce this book. Brodesser-Akner is a journalist who has written for the New York Times and GQ, interviewing celebrities of the calibre of Tom Hiddleston and Gwyneth Paltrow. She claims to have started this novel after her editor showed distain for the idea of writing an in-depth article on modern divorce.

Fleishman is in Trouble is a sophisticated examination of modern dating, marriage and divorce. While the story mainly centres on the disintegration of Rachael and Toby Fleishman’s marriage, it is also a story about the extent to which wealth and privilege can protect one’s self and family from the vagaries of the world and our own frailties. To an extent, then, it resides in that same class of novel in which I place The Great Gatsby, a book I was never found of, because I always found it hard to be sympathetic with wealthy, privileged people who nevertheless made their lives miserable. I have been told I am wrong about the book, but there it is. Nevertheless, I think many will find the lives of Brodesser-Akner’s well-to-do compelling and sympathetic, even if we don’t particularly like them. Readers might dislike Toby for his exploitation of women across dating apps and his tendency to focus upon their anatomical assets. Rachel might be criticised as a neglectful mother or for her social climbing. And so to for many of their friends, rich and privileged beyond the hopes of the Fleishmans, who are self-absorbed and plastic, defining themselves through slogans emblazoned on their tank tops: BUT FIRST, COFFEE; BRUNCH SO HARD; THE FUTURE IS FEMALE. As Brodesser-Akner’s surrogate, Elizabeth, suggests, wealthy women content to shop and drink martinis all day

are inured to the ills of the world, but Rachel, self-made and financially independent, is aware that she still had to tiptoe around the fragility of a man…

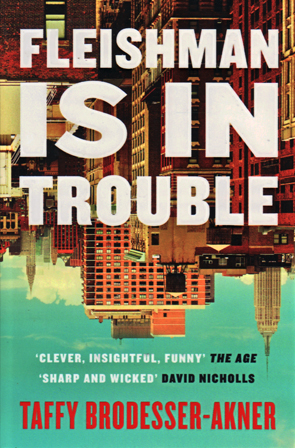

Brodesser-Akner has shaken up the divorce story, turned it upside down, so to speak, much like the image on the cover of the novel. This is a story about women and it addresses feminist issues, but the first impressions given by the book (imagine you are standing in a bookshop for a moment, knowing nothing other than what the cover and an initial examination might suggest to you) would seem otherwise. If I was to say that the cover has a masculine tone, you might object to the assertion, but you’d broadly understand what I mean based on conventional paradigms. The image of the city is masculine because women have traditionally been associated with domesticity and men the wider world. The city is upside down, suggesting danger, or problems which must be faced in that world, an inference supported by the word ‘trouble’ in the title. The font used is bold and muscular, and while the protagonist’s name might refer to either a male or female character, there’s going to be a study somewhere that says even now our minds are trained to assume a male protagonist first, and the fact is, as we start to read Brodesser-Akner’s novel, this would seem to be correct.

Toby Fleishman is a hepatologist, a doctor specialising in problems related to the liver. His wife, Rachel, runs her own talent agency. They are well off. Rachel desires to live in the Hamptons, but they are not quite that well off, not yet, but she has been making moves to insinuate herself into that crowd. She is a social climber, she is ambitious and she works hard. Toby, on the other hand, is aware that his status as a doctor isn’t quite what it once would have been, and while he makes a good living, Rachel knows her husband could do better for the family with a promotion within the hospital, or if he accepted a position offered to him by Sam Rothberg, a Hampton resident who heads a pharmaceutical firm. But Toby is not ambitious like Sam and finds Rachel’s dedicated work ethic, her acquisitiveness and social ambition, off-putting. Toby likes to feel pure. He does not sully his hands at work with needed fundraising, preferring to maintain a traditional doctor’s role and patient care.

Toby is firmly the protagonist of this story and a quick perusal while standing in the bookstore will support the initial impression of a masculine text as you read the opening lines of the novel: Toby Fleishman awoke one morning inside the city he’d lived in all his adult life and which was suddenly somehow now crawling with women who wanted him.

Toby’s metamorphosis (the allusion to Kafka seems vague, but Toby’s transformation is startling for a short man who never pulled women when he was younger) is the product of online dating apps available on his phone. A work colleague, Joanie, has encouraged him to try them after his split with Rachel. Now, women send him pictures – posing with strange expressions of lust, exposing a part of or all of their breasts, or sending photos of their genitalia – in what initially reads like a version of the hyper-sexual Lynx advertisement, with horny women converging on Toby from everywhere across the city. Is it an accident that Toby’s name is only one letter different from ‘flesh man’? His newfound popularity would seem to be the stuff of male fantasy, but by the third page we understand Toby is uneasy. He has asked for the divorce from Rachel, but he cannot shake the feeling that, Something is wrong. There is trouble. I am in trouble.

Even more peculiar in all this is the narrative perspective, itself. The Great Gatsby seems to be predominantly written from a third-person perspective, even though Nick Carraway acts as a first-person narrator. Similarly, in Fleishman is in Trouble we are aware from the opening paragraph that a first-person narrator is lurking in the background, with the use of the collective first-person ‘our’, along with other tantalising hints in the first thirty pages. But it is thirty pages into the story before we discover our narrator is female, a friend of Toby’s and Seth’s from their college days, and a further three pages after that before we are given a name – Elizabeth Epstein – and introduced a little to her life with Adam, her husband, and her role as a stay-at-home mother, having once worked as a journalist. Fleishman is in Trouble, it turns out, is a peculiarly layered narrative. Elizabeth’s intrusion into Toby’s story increasingly destabilises the seeming ‘maleness’ of the narrative perspective.

And this is the true strength of this novel. I think those turned off by the characters, their social class or the perspectives offered, may be missing the point. We are invited to feel sympathetic for Toby for much of the novel. Sure, he initiated the divorce from Rachel, but we are given long insights into his reasons: Rachel was overly engaged with social aspiration, was rarely at home because of her work and had become emotionally violent. She seemed detached from their two children, Hannah and Solly. Yet even through Toby’s narrative, as it is given to us by Elizabeth, we understand something has fundamentally gone wrong for Rachel. She lost her mother when she was young, was raised by a loveless grandmother, has endured a horrific birth in which she felt violated by her doctor, and has been seeking help in support groups. She works hard because that is her response to insecurity. The breakdown of relationships in the New York world of the elite – and by extension, to all relationships – are not the result of bad wives and good husbands, or bad husbands and good wives, but a result of the pain of coping, of misunderstanding and the failure to empathise. When Rachael goes missing for several weeks, leaving Toby to look after the children and juggle his burgeoning sex life, he imagines a thriftless and indulgent affair undertaken at the expense of himself and his children. For Toby to really understand his marriage, he will need to understand Rachel’s disappearance.

But to finally appreciate Brodesser-Akner’s achievement, you need to consider her sophisticated narrative perspective once more. Elizabeth rejected Toby as a lover – not an advance he made, but the possibility of it in her own mind – when they were younger. Now, as she watches the disintegration of Toby and Rachel’s relationship, she understands that her own marriage is in trouble. She feels herself drifting from Adam. By relating the story of Toby Fleishman, Elizabeth acknowledges to herself that they have commonalities. And Elizabeth, as a journalist, is transparently a surrogate for Brodesser-Akner (Maybe I’ll write a book about us,

Elizabeth tells Toby). This is not to say that Brodesser-Akner’s marriage is in trouble (by all accounts it’s doing just fine) but to acknowledge that as a journalist, Brodesser-Akner has made a living by interviewing subjects to tell stories. The interviewee is the surrogate through which a story is told. But in Fleishman is in Trouble this becomes a key point upon which the story is based. As a journalist, Elizabeth is often uninspired by women she has interviewed, as their stories are mostly meta-narrative: about the problem of getting to be interviewed; the problem of not being taken seriously. Whereas the stories of men resonate for her: They didn’t have a fear that they didn’t belong. They hadn’t any obstacles. They were born knowing that they belonged…

. When she first interviews a man she says I understood we were talking about something more like a soul.

Elizabeth’s insight is that to advance a female narrative or project female concerns, the best strategy is to Trojan horse yourself into a man, and people would give a shit about you.

It is both clever and sad. Toby Fleishman is the novel’s protagonist, but the goal of the novel is not to privilege his position, but to moderate its more strident aspects through a growing awareness of what Rachel has endured and what Elizabeth secretly struggles to understand about her own relationship.

Elizabeth speaks about Archer Sylvan, a fictional journalist who writes an equally fictitious article, Decoupling, judged to be exemplary journalism in Elizabeth’s professional circle. Elizabeth, herself, has aspired to write an article like it. As the title suggests, the article is about divorce: perhaps that article Brodesser-Akner never got to write, or at least a version that might have been written in the 90s by a male journalist. It tells the story of a man, Mark, and his experience of divorce. Later, when Mark’s unnamed ex-partner approaches Sylvan to tell her side of the story, he does a hatchet job on her. This book feels anything but that. Sadly, there is a female deference to the male perspective throughout – according to Elizabeth, it is the only way – but it is in the service of something more balanced and civilised: that all marriages are complicated and private, and by the time a marriage is over, maybe everyone can claim a totally justified grievance.

Fleishman is in Trouble is a sophisticated representation of the complexity of relationships, which humanely balances the problems of divorce. Strangely, you feel sympathetic to all the characters by the end. But what sticks in my mind is the problem that the narrative voice illustrates throughout: that women still find difficulty to have their perspective taken seriously; to be listened to; to receive the empathy which they are expected to confer. It’s a great novel and highly recommended.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!