First Person is conventionally written as a first person fictional narrative, but the book has an interesting genesis, which makes it something of a hybrid.

Kif Kehlmann, our narrator, recounts the period in his life when he was commissioned, as an aspiring but as-yet-unpublished fiction writer, to ghost write the memoir of Ziegfried Heidl, who, as former CEO of the Australian Safety Organisation (ASO), has swindled millions of dollars from banks, and in turn, has caused some of them to collapse. Heidl is due to face trial within weeks and is bound to go to jail for a very long time. In the intervening period, Gene Paley, head of TransPacific Publishing, needs Heidl’s memoir to be ghost written. The schedule is tight. Heidl has signed a contract for the rights to his story, but now it needs to be written before he goes to jail, along with the release papers to be signed as to the veracity of the account.

The only problem is, Heidl is a nightmare to work with. He’s already driven several writers away with his impossible work practices – he basically refuses to talk about himself or work properly on the manuscript, and instead seeks easy publicity from the tabloid press – and now the publisher is desperate enough to seek the help of the untried Kehlmann. For his part, Kif is also desperate. His wife, Suzy, is pregnant with twins, he’s just been sacked from a fairly pointless job and his aspirations to become a novelist are stillborn. Kif is little more than a dilettante. But the lure of money is too much for Kif, and he agrees to tell Heidl’s story.

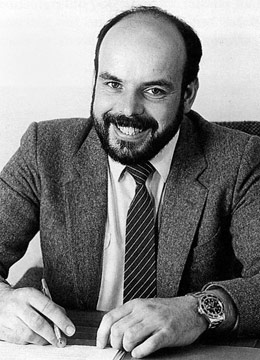

The interesting thing about this is that, long before he won the Booker Prize for The Narrow Road to the Deep North, before he had even published a novel, Flanagan was himself commissioned to ghost write the memoir of a real life con man, John Freidrich, originally a West German national, who claimed to have been born in South Australia. During the 1980s he was the CEO of the National Safety Council of Australia (NCA). After the collapse of the NCA Freidrich went on the run. Freidrich’s story and the speculation as to his whereabouts was fodder for the tabloid press for several days. I remember the fascination I personally had with Freidrich as I followed news of various sightings. Freidrich was portrayed as a trickster by the press, and looking back, it seems to me that Freidrich was inserted into a national narrative that idolised bushrangers too clever for the police, or who were somehow their moral superiors. There was an element of comedic sleight of hand in the way Freidrich evaded attempts to capture him. At least until they caught up with him in Perth and Friedrich seemed to lose his superstar gloss.

Flanagan worked with Friedrich during the period he was preparing for his trial and has related in media interviews about this book how Freidrich refused to cooperate with him, told lies, and how he and Flanagan had screaming matches in the publisher’s offices. Friedrich even carried a gun. Eventually, Freidrich’s story was told by Flanagan in Codename Iago, a book The Australian newspaper claimed was one of the least reliable but most fascinating memoirs in the annals of Australian publishing.

It’s clear that the whole experience is grist for Flanagan’s creative mill when he came to write First Person, a book partly a memorial to the fictional Heidl, and thereby Freidrich, part confessional, part fiction, part fact. But as narrative fiction, First Person is freed from the strictures of a putative non-fiction memoir. Flanagan, now a more experienced writer, uses his association with Freidrich to craft a story about fiction and Australia.

For Flanagan’s story is also about fiction writing. It’s not a surprising subject for a man who has made making things up a living. In a conversation Kif has with his former editor, Pia Carnevale, Pia challenges the efficacy of fiction writing:

It’s fake, inventing stories as if they explain things … Plot, character, Jack and Jill going up the hill. Just the thought of a fabricated character doing fabricated things in a fabricated story makes me want to gag. I am totally hoping never to read another novel again … Autobiography is all we have …I don’t make it up. I hate stories. We all hate them. We’ve heard them all before. We need to see ourselves.

It’s the problem Kif struggles with throughout the book. Tasked with writing a true account of the life of a man who not only does not cooperate, but endlessly reinvents himself through lies and contradictions, Kif is faced with the uncertainty of the line between truth and fiction, between words and representation and between his own ideals stripped bare by his experience, and the reality of his talent. Ironically, it is his own memoir we read, not Heidl’s, and in his attempts to create fiction, Kif increasingly sees himself as a charlatan, as a man not unlike Heidl.

Interestingly, Kif associates his experiences with Heidl with the old Australian myth of mateship. Heidl inveigles Ray, a childhood friend of Kif, to do his bidding through his appeals to mateship, and uses the same ploy on Kif. But when employed by Heidl, ‘mateship’ itself is exposed as a construction, a lie and a manipulation. Mateship is a story, Heidl’s stock in trade, as is everything else:

Stories are all that we have to hold us together. Religion, science, money – they’re all just stories. Australia is a story, politics is a story, religion is a story, money is a story and the ASO was a story. The banks just stopped believing in my story. And when belief dies, nothing is left.

For Heidl, the truth is negotiable, his fabrications morally neutral and the world is created in a moral vacuum. This, it seems, is the natural outcome of post-structural ideologies that posit everything as relative. Pia’s desire for autobiography isn’t a solipsistic urge, although she knows she lives in that kind of society: it’s a desire for a centre; some way to overcome having known Heidl and his world.

Having read a little about Flanagan’s connection with Freidrich before I read the novel, I was surprised at how closely Flanagan’s experience seems mirrored in Kif. Naturally, there was a point where the narrative takes a turn and goes its own way, but one feels that it is an exaggeration of facts rather than fabrication, perhaps a meditation on that old question fiction is best placed to ask: What if…?

At times I felt the narrative is a little constrained by the facts, and sometimes progresses slowly with a great deal of soul searching on Kif’s behalf. But Flanagan’s narrative raises interesting questions, too, about fiction, our relationship to lies, and our identity and our relationships with others. Ultimately, this is what makes the fiction worthwhile, whatever Pia Carnevale may believe. Autobiography, if it is faithful to its subject, can only reveal so much. It’s those questions that fiction is able to ask, perhaps even questions Flanagan asked himself while writing the book, that are more unnerving and more revealing about our natures. This is what Heidl does for Kif. He questions his assumptions, even if his stories are bullshit. He makes Kif doubt his world and its certainties.

But most interestingly, there is possibly an element of truth in everything Heidl says. This is an interesting and philosophically compelling book.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!