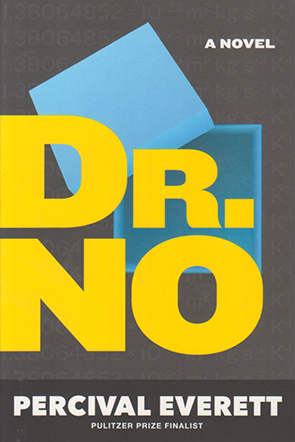

My reading of Dr. No comes just after reading Cormac McCarthy’s Stella Maris, and my having read The Trees by Percival Everett in November last year. So what? you might ask. First, I mention it because, by chance, characters in Dr. No have similar academic interests as McCarthy’s Alicia. Like Alicia, Everett’s Eigen Vector, a kinda Bond-woman to Everett’s villain, John Milton Bradley Sill, is a Mathematics professor and specialises, like Alicia, in topology. Everett’s protagonist, Wala Kitu is also a Mathematics professor whose studies of ‘nothing’ also touch upon theories about the nature of the universe and allude to similar intellectual concerns covered by Stella Maris. Mathematicians like Gödel get mentioned in both books and there’s also talk about Platonic forms. It’s hard not to notice this stuff. Then there is The Trees, Everett’s novel that precedes Dr. No. It has several similarities to this work which reinforce an impression about Everett’s intellectual interests and background. It’s hard not to make these comparisons in your mind as you read.

Dr. No, like The Trees, is divided into short chapters, which are clustered into short parts, each part bearing names which are sometimes merely descriptive, and at other times tantalising, even confounding. Everett’s final section, titled ‘Il n’y a pas de hors-texte’ is a quotation from Derrida’s On Grammatology, and it suggests a paradox which I will refer to after speaking a little bit about the story, first.

Dr. No just so happens to have been published when I was in the middle of re-watching the complete James Bond collection, from Connery to Craig. The plot, I realised, according to the blurb on the cover, is straight out of Goldfinger: a scheme to rob Fort Knox in Kentucky. Super-wealthy John Milton Bradley Sill announces to Wala Kitu that he has decided to be a supervillain. Wala Kitu, a Mathematics professor, “on the spectrum”, whose name means nothing (both his first and last names in Tagalog and Swahili) and whose theoretical interest is in ‘nothing’, is engaged by Sill to help him carry out his heist. Because, when Kitu speaks about ‘nothing’, he is speaking not about zero, or an absence, or negation, but non-existence (if that is even a way of explaining it); like something that was never there. Kitu has spent years of his career on a quixotic quest to identify the existence of ‘nothing’, the paradoxical implications of that notwithstanding, and this is Sill’s interest in Kitu. He is willing to pay Kitu three million dollars for his help to steal ‘nothing’ from Fort Knox. Sill believes ‘nothing’ is being held in Fort Knox, and if he can acquire it, it will prove to be a formidable weapon against his country: “This country has never given anything to us and it never will. We have given everything to it. I think it’s time we gave nothing back.” Like many supervillains before him, Sill is out to destroy the place, but only with an exotic weapon.

This is where Everett’s use of ‘Il n’y a pas de hors-texte’ interested me: Here, it seems, is yet another iteration of ‘nothing’, paradoxically creating something from nothing through the sheer power of language and repetition. But it is a concept that so defies of our lived experience and everyday reality, that it can only exist within the text, and a reader’s conceptualising of it. Because, Kitu insists, that what he means by ‘nothing’ is not just another name for dark matter or anti-matter or any other weird concept that science has introduced that has now entered common parlance. It is something beyond our experience that Kitu struggles to understand and articulate, himself. Derrida’s line is often translated as “There is nothing outside the text”, which would seem to style Kitu’s ‘nothing’ as a piece of textual play, and a belief in the text, itself, as a complete whole. And Everett does play with the paradoxical and nonsensical possibilities of ‘nothing’ in many exchanges Kitu has in the novel: “I am an expert in nothing,” Kitu reiterates to Eigen, and when nothing is used as a weapon against America we are told, “nothing will happen”. Except ‘nothing’ here is, of course’ something. The town of Quincy is disappeared by a beam of nothing, except that it just doesn’t disappear, it in fact never was. Maps that once marked the town, the shape of borders and even peoples’ memories now reflect this reality.

But I don’t think the paradoxical uncertainties in the text or the linguistic play is really the whole point of the novel. If that were so, Dr. No would be little more than a quirky parody of Bond. We would identify the similarities it shares with Goldfinger and laugh because most of Bond before Craig’s tenure is fairly laughable (I refer to the films because I have only read one of the novels). And we’d notice that ‘Dr. No’ – no-one assumes this name in the novel, not even Sill – is another permutation of Nothing: a negation. But Derrida’s famous maxim is usually mistranslated, and I think it would be more accurate to say that Derrida is suggesting the text has no signifying or semantic boundaries. In Sean Gaston’s Reading Derrida’s Of Grammataology Derrida is cited as saying:

What I call “text” implies all the structures called “real,” “economic,” . . . in short; all possible referents. Another way of recalling once again that “there is nothing outside the text.”

Read in this way, Derrida doesn’t bind the text within its covers, but sees context – its social milieu, history and political environment – as a part of the text, itself: how it is shaped and its purpose, to which I might add, the receptive context of the novel, which is the lived experience, attitudes and education of its reader.

This seems like a rather pedantic fixation upon one section heading, but let’s face it, Walu Kitu’s conception of nothing and its application within the novel is just plain impossible and a wonderful piece of nonsense. Which is not to say that fiction should only remain within the bounds of the possible. Instead, what broadens the appeal of Dr. No – what it also has to offer us – lies beyond the cultural play that parody allows, in the wider satirical boundaries of social and political context. Given this, Dr.No bears some further comparison with The Trees. As in The Trees, Sill’s heist represents a kind of Black uprising against institutional racism in America. Sill is inspired to strike back at White America after the deaths of his parents and the assassination of Martin Luther King. There is also the bumbling government agents, a type familiar from The Trees, one of whom is incongruously named Bill Clinton. Everett’s use of names of the famous for some of his characters is also apparent in The Trees, as are the groan-worthy jokes, comic situations and a general sense for the ridiculous.

But what is of greater import is that Dr. No, like The Trees, reflects upon Trump’s America. Trump is not given quite the same air play as he receives in The Trees, but the Vice President, Neil Shilling (Shilling / Pence – get it!?) plays a prominent part in Sill’s dastardly scheme, and there is no doubt who the President really is or what Shilling thinks of him: “. . . that fat buffoon,” Shilling calls the unnamed president, and says, “I’ve hated kissing his orange ass for these past years. Stable genius? Stable asshole.” Kitu says of Sill’s plan to destroy America, “He wants to make America nothing again”, recalling Trump’s famous MAGA mantra. In its wider context, Everett’s ‘nothing’ represents an existential threat against America, driven not by ideology or vision, but an atavistic hatred. Sill’s seething contempt and desire to destroy is on behalf of black America – his plan is inspired by the deaths of his parents and Dr King, after all – but those tragic events are the result of America’s own racial history. As in The Trees, Everett envisions apocalyptic possibilities for America, borne from its own hatreds.

Despite the fact that all this makes would seem to elevate Dr. No as a more difficult read, it is not. It’s allusions to Mathematics and Science are far lighter than McCarthy’s in Stella Maris, and feel more like window dressing. The wider context of the story is important, but it is not the most prominent element of the writing. In short, as in The Trees, Everett wears his erudition lightly. On every page his goal is to entertain and push everything along, with funny allusions and wordplay. Not everything is highbrow. A villain who fails to meet his quota is dropped unceremoniously through the floor, along with his chair, into a pool of sharks. If you don’t recall this happening in Bond, you’ve probably seen the same scene in Austin Powers, another Bond parody. There is also Kitu’s one-legged dog whose poos feature prominently in the story and who acts as a conduit for Kitu’s dreaming thoughts. And there’s a ubiquitous butler, DeMarcus, who has an impossibly keen sense of where he must be and what is needed in every situation. The book really is as wonderfully ridiculous as all this.

Nevertheless, I think Dr. No falls a little short of The Trees. In that novel our attention is held by the bizarre murders which have a tangible claim on our curiosity. The driving element in Dr. No is more esoteric and the stakes are impossible to really conceive until quite a way into the book. Dr. No requires a level of faith from the reader, that Kitu’s dissertations on ‘nothing’ might eventually amount to something. The plot is not quite as cohesive as The Trees either. There are digressions from the central line of the story which seem unnecessary, particularly a whole chapter devoted to Kitu buying a car. And while the ending is in the style of the ending for The Trees – an ending which blew me away – I felt information from earlier in the story undercuts its import, apart from my feeling that it hadn’t progressed beyond the wordplay common in the novel, to offer something compelling and new: something surprising and, perhaps, profound.

Even so, Everett is a great writer who somehow takes serious and difficult subjects and turns them into page-turning stories that read like light popular fiction. It’s not something many writers could achieve, and this sets him and his books apart from many other fun reads you might otherwise choose.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!