Dirt Town is the first published novel by Hayley Scrivenor. I received an advanced reader copy which includes two letters to the reader, one from the author and another from the publisher, which will not likely be included in the commercial version due out late this month. The copy I received was released for promotional purposes, so I assume the publisher and author would welcome the wider distribution of their promotional letters. I will refer to some of what they have to say in this review, so if you wish to view the author’s letter, click here. If you wish to view the letter from the publisher, click here.

‘Dirt Town’ is a child’s variation of the town name Durton, a familiar place if you have travelled through regional Australia, even though Durton, as the author tells us, is fictional. That is the first thing to say about this rather interesting crime novel: Dirt Town conveys a strong sense of its place and people. It is a smart literary crime novel which is emotionally engaging. It draws us in immediately, not only to a crime and how it will be solved, but it immerses us in the lives of the people of Durton, whose personal circumstances are cause for reflection. These are real people and their lives cannot be dismissed as irrelevant to our own. We are forced to confront the terrible possibility that who we believe we are is not as definitive as we believe, nor are the circumstances that will draw out our future self.

Scrivenor’s biographical note tells us that she is “originally from a small country town”: that, and her acknowledgment of Aboriginal custodianship of the land in her acknowledgements pages suggest she writes from a strong sense of place and its links with identity. That is not to say that Aboriginal issues are strongly foregrounded within the novel, however. There is only one moment, when Detective Sergeant Sarah Michaels recalls something her former girlfriend said to her, that our focus momentarily shifts from the investigation, the search for a missing child, Esther Bianchi, to contextualise modern criminal violence within a colonial past: “Baby, something bad is happening everywhere. This is Australia. Think about whose land you’re standing on. The catastrophe is ongoing.”

Scrivenor sets her narrative in a modern Australian country town that even the local children sense is dying. The date is specific – 30 November 2001 – when Esther Bianchi fails to return home from school. Her mother, Constance, is not a ‘native’ of Durton – she did not grow up in the town – but rather, moved to Durton several years before at the urging of her incredibly good looking husband, Steven Bianchi. Steven grew up in Durton and he believes, ironically as it turns out, that Durton will be a safe wholesome place to raise a family. Constance has not exactly been accepted by the town’s community, however. She is perceived as a little too remote. But she has made friends with Shelley Thompson whom she speaks to regularly, even if Shelley and her husband Peter never visit their house to socialise. This makes Shelley and Constance’s relationship, as strong as it might appear, seem somewhat provisional. And this sense is borne out by a terrible revelation Shelley is about to make to Constance.

Many of the relationships in the town seem fractured or fraught. Clint Kennard may be beating his wife, Sophie: Evelyn Thompson thinks it best her daughter Veronica (otherwise known as Ronnie) not know the identity of her father; and while Peter and Shelley Thompson’s marriage might appear solid enough, financial pressures are about to have a big impact on their lives.

Part of the appeal of this novel lies in these troubled relationships. It is not merely that they may provide motive and means when the lid is slowly peeled back by Sarah Michaels’s investigation of Esther’s disappearance. The characters and their relationships are integral to a philosophical approach this novel takes to crime, which sets it apart from many crime novels. Depending upon the genre, many crime novels, especially older crime novels from the Golden Age, are about the restoration of order. A crime – and murder is the most pernicious of crimes – undermines the sense of social order and our humanity. Only by identifying the perpetrator can order and humanity be restored. Small town settings, as Scrivenor uses here, would traditionally be stock in trade for this kind of scenario: isolated with a limited set of suspects, given that the facts of the case point to a perpetrator with local knowledge. But Scrivenor turns the assumptions of small town life, the kind espoused by Steven Bianchi, around. Even an outsider like Detective Sergeant Sarah Michaels, for instance, comes with personal baggage, a fact not lost to her as she sets out to interrogate the town’s residents. This is fairly typical of a lot of crime fiction, too. Hard-boiled detectives of the 1940s firmly established the damaged lives of detectives who plied their trade. But Scrivenor’s portrayal of Sarah Michaels is not attempting gritty realism. Her backstory, which mainly focuses on her torrid break-up with her former girlfriend, Amira, has pushed Sarah to an emotional edge which could easily have resulted in her indictment for violence, and might still ruin her career if the details are ever made public. As she remembers a lesson her father once imparted to her, Sarah’s story reveals to us a philosophical underpinning in this novel. She remembers that as a child her father had once pointed to a thin lace table runner on their dinner table, and used it to represent the lottery of being born: those who are born to privilege and opportunity on one side believe their lives represent an essential quality about themselves: “Everyone […] thinks they’re there because they wouldn’t ever do the sort of thing that gets you into that kind of mess.” But the point of her father’s story is to disabuse Sarah of this belief: “Things happen, and anyone can end up there,” he tells her. He adds: “Even your mother.”

This is a quality that sets Scrivenor’s story apart from a lot of crime fiction. Sarah Michaels is aware of the abyss into which hope and prospects might tumble; that ill-fated moment that tips someone’s life upside down. Scrivenor’s narrative isn’t moralising but speculative in this regard. It follows all the regular tropes of detective fiction – the crime, the cast of suspects, the procedure of the investigation, false leads and surprise revelations – but the novel speaks to the vagaries of existence: of the randomness of life and the trap of circumstance than leaves everyone vulnerable.

To this end, narrative voice is an interesting feature of this novel. The story is told from multiple perspectives, thereby abandoning a more traditional detective narrative that makes the investigation, itself, the central focus of the story. By placing us in the mind of Constance as she faces the reality that her daughter may not be coming home, or Shelly whose past is tormenting her, or Sarah whose determination to conduct a professional investigation is punctuated with concerns about her personal life, we are most focussed on the circumstances that shape these characters. But of greater interest, still, is the use of children’s perspectives, whose voices form a substantial part of the narrative. Lewis, the son of Clint and Sophie Kennard, is isolated at school and struggling with guilt over his feelings for his friend, Campbell Rutherford. He has seen something the day that Esther disappeared that might be important to the investigation, but his shame prevents him from doing the right thing. And Veronica – Ronnie – whose friend, Esther, is missing, is a smart kid who is obsessed with llamas and wonders who she really is, because her mother won’t say who her father was.

But of most interest is Scrivenor’s use of what she terms a “chorus of children who have access to things they shouldn’t, or couldn’t, know about what really happened to missing girl, Esther Bianchi.” Without identifying a specific individual perspective, this ‘chorus’ speaks in the collective voice of ‘We’, and like the Greek Chorus used by ancient tragedians, its presence heightens the import of individual misfortune and evokes a mythic quality. The discovery of Esther’s body in the opening chapter, told through the voice of the collective ‘We’, is far more dramatic than its revelation later on:

What does it all mean? For now, we can only tell you that we were there, that we watched blood seep through the man’s sleeve as he walked away from Esther Bianchi’s body and looked around him, as if the answer might be found somewhere in the open field.

The collective identity Scrivenor ascribes to the children of the town is a conceit that mostly works well. It raises the death of Esther Bianchi to a tragedy, because we see it is not an act that exists in a moment, but as a formative experience in the collective conscience of the town’s children. This is important to acknowledge, because we see the outcome of their parents’ lives, whose formative experiences when young are now bearing down upon them as the investigation into Esther’s disappearance begins.

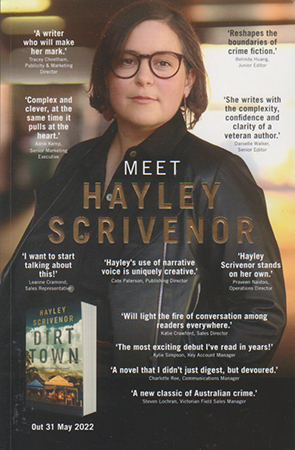

The choric voice also expresses the key tenets of the narrative: that “we all do stupid things as children”; that “bad things happen”; and “sometimes people made them happen.” By employing this device, Scrivenor reminds us of our own formative experiences, perhaps sometimes best forgotten, as Cate Paterson, Scrivenor’s publisher, points out. For this reason, Dirt Town is not just a Whodunit – a puzzle to be contemplated for enjoyment, although there is scope for that in the book, too – but a meditation on our own lives and the circumstances that have shaped them.

The publisher is keen to make comparisons between Dirt Town and previous successes had by Pan Macmillan with new Australian authors over the past decade. Hannah Kent’s Burial Rites, set in 19th century Iceland is probably not an obvious comparison to make with Dirt Town, but Jane Harper’s The Dry is. The Dry, also reviewed on this website (although I did not read it but I saw the film) has similar elements to Dirt Town: its country town setting and the sense that the past is now catching up with some of the characters. It seems reasonable to suppose that those who enjoyed The Dry would likely also enjoy this offering from a new Australian author. I would certainly recommend it to lovers of crime fiction.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!