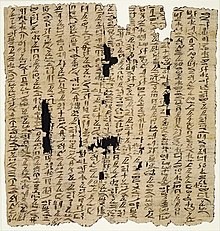

This is an unusual mystery from Agatha Christie, her only mystery that did not have a contemporary setting. Instead, it’s set around 2000 BCE, on the West bank of the Nile at Thebes in Egypt. It’s actually considered to be the first historical mystery published. We have a huge assortment of historical mysteries these days but this would have been quite a novelty in 1944. Christie dedicates the book to Professor Stephen Glanville, a friend and Egyptologist. She says that the idea for the book originally came from him, and that she would not have written it without his help and encouragement. She doesn’t explicitly say, but I assume it was he who drew her attention to the Heqanakht papyri, a collection of real letters translated by another Egyptologist, Battiscombe Gunn, which form the basis for this story.

The book centres on the family of Imhotep, a Ka-priest, and is narrated by Renisenb, Imhotep’s daughter. Renisenb has only recently returned to her father’s home, following the death of her husband. Initially, she thinks she has returned to a world unchanged from what she had left eight years earlier. She listens to her family discuss everything, from her two older brothers arguing over how best to manage their father’s business in his absence, to the squabbles and power struggles of her two sisters-in-law, to the whining of a family retainer and to her grandmother fussing over linen with her slave girls, and she feels like she has never left. Renisenb at first welcomes her return to this familiar world, hopeful that she can forget the pain of her husband’s death. But it doesn’t take long for her to feel an undercurrent of change, even though she cannot identify the cause; she senses some dark presence lurking beneath the calm surface of daily life. Renisenb is both an outsider who can see her family’s behaviours more clearly than the others, and an insider who cares for these people and who doesn’t want to see anything bad in anyone.

Suddenly there is a huge change to family dynamics when Imhotep returns from his property in the North, bringing with him a beautiful, young concubine, Nofret. Nofret quickly antagonises everyone in the family. Tensions emerge as everyone seeks to be the one who gains Imhotep’s favour, and worries about their position in the family and their inheritance. Then Imhotep is called away, back to the Northern property, leaving Nofret behind to deal with the barely contained resentment of his family.

After the opening chapters set up the background of family life in a wealthy Egyptian household and establish all of the characters for us, Christie starts to build tension between the characters, and finally gives us the first murder of the book. This is followed rapidly by a second and third murder, and a fourth and … I actually forget what the body count ends up being in this one, but certainly no one could complain about a lack of murders. It’s one of those stories where you think that the only person who will be left standing by the final chapter is the murderer, and then you’ll know who it is. All of the characters are convinced quite early that they know who the murderer is: they KNOW it’s the ghost of the first victim, out for revenge on them all. This is possibly the part of the book that most establishes its setting in ancient Egypt and the Egyptian thinking of its characters, who maintain a deep belief that a bloodthirsty ghost has returned and that the best way to deal with the problem is to make offerings to Imhotep’s dead wife, asking her to sort things out in the afterlife. This is definitely not a modern mystery with a competent police force or private detective to work out what is going on.

I think I’ve read enough of Christie’s stories over the past few years to get a feel for the seemingly innocent statements that, if read in a slightly different way, give a major clue to the plot. It happens in Death Comes as the End too. I read one paragraph quite early in the book (before the first murder) and it instantly struck me as important. I felt quite satisfied when the reveal at the end confirmed that I had got it right; a very rare thing for me with Christie’s mysteries.

This might have been Christie’s only foray into history, but she handles it well. She creates an interesting setting and an entertaining murder mystery with a high body count. I don’t think this story would have worked in a contemporary setting, even if all the characters and their motivations could easily translate to a modern setting, as it needed the lack of a formal murder investigation to work. But it was a fun mystery and I really enjoyed it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Comments

No one has commented yet. Be the first!