Stefan Zweig's ‘Chess Story’ is a tour de force that can be finished in just one go by even a slow, distracted reader like me. There is no reason why you wouldn’t want to finish the story once you have read the first few pages. It has the structure and pace of an adventure story. The narrator spots an opportunity for adventure and he brings together a group of adventurers. A hero with a troubled past emerges but he must be convinced to lead the assault. There is a showdown and there are consequences for the hero. To reveal any more details about the outcome would take the joy out of reading story for others.

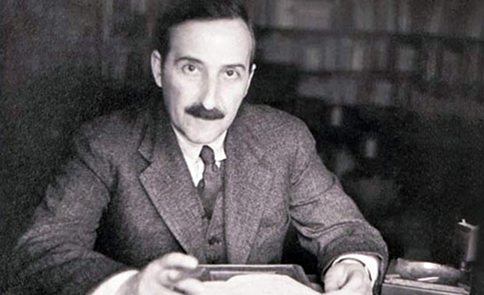

The unnamed Austrian narrator boards a ship from New York to Buenos Aires. The reigning chess grandmaster Mirko Czentovic has also joined the vessel. Czentovic was raised by a priest after the death of his father in a remote Hungarian village. He has difficulty reading, writing and perhaps even thinking and does not understand social etiquette. He is unable to express what is going on inside his brain and cannot, unlike the other grandmasters and many chess enthusiasts, play without a physical board present before him. Yet Czentovic knows one thing very well: he knows how to win a game of chess. The narrator reflects that there is no creative genius behind his methods but a kind of brute force that is devoid of any art or higher thinking. Coming from a diffident country this lad has turned into an arrogant and reclusive practitioner of a trade, who has his mind set on minting as much money as he can through playing chess.

The narrator takes a fancy for understanding the psychological makeup of Czentovic and in his attempts to draw him out of his cabin, he bands together a group of travellers on board for this quest. An ambitious Scotsman bankrolls their endeavour. Soon, they realise that they are no match for Czentovic, until a mysterious stranger appears on the scene who can quote moves from the games of grandmasters past while claiming not to have touched a chessboard in over two decades. The party tries to convince this stranger to play against Czentovic. The story then takes a turn as the stranger, Dr. B, reveals his life story to the narrator. The nervous Dr. B will leave a lasting impression: as a demolished man; a man who seems to have imploded. His tormentors have sliced out a part of him, bit by bit, layer by layer.

The tales of the two chess players are dovetailed without losing pace as the story moves towards its end. The focus remains on keeping the narrative taut, giving one detail after another. There is no great character development beyond the bare requirements of the story. The characters leave an impression but in no way “jump of off the page.”

There is also quite a bit of hypocrisy from the narrator. At the outset he says he is interested in studying monomaniacs and that is his reason to pursue Czentovic. Yet he scorns Czentovic because of the way he acts, for the mere reason that he does not know how to conduct himself among “civilised” society. It’s likely that had Czentovic come from a more gentrified background, the narrator would have tried to justify his arrogance and general stupidity. Surely, Czentovic deserves gentler treatment from those around him. Yet when the narrator finds the ultimate monomaniac, Dr. B., he seems to have no interest in studying him. In fact, he tries to shield him from his mania in the end. Why does he do that? Perhaps because they are fellow countrymen; perhaps because Dr. B. comes from the opposite end of the social spectrum from Czentovic and his sufferings are more relatable to him.

After reading this book I was surprised to discover it is listed in Peter Boxall’s 1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die, along with a few other works by him. Perhaps a keener and more literary mind would find greater salvation in its pages, but for a layman like me, it was simply a good story. I thoroughly enjoyed reading it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter