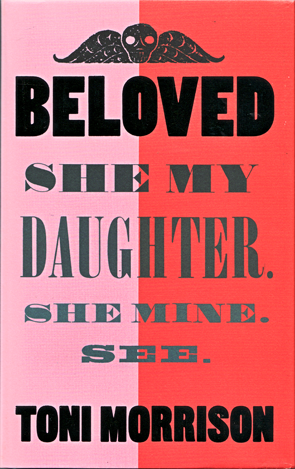

Margaret Busby tells us that Toni Morrison said of her Pulitzer Prize winning novel, Beloved, “It is outside most of the formal constricts of the novel, but you've got to call it something. Just so long as they don't call me a Magic Realist.” It’s an interesting statement, given its defensiveness and implicit contempt for the genre. Yet Magic Realist elements are often the mainstay of writers of historical fiction who need to realign their readers’ perspective and introduce new insights, especially to challenge colonialist narratives. The ancestors of African Americans weren’t technically colonised, but they were exploited, nevertheless. So, first up, if you don’t like Magic Realism you may be prejudiced against Beloved, since its plot turns upon these elements. 124, the only name given to the house in which Sethe lives with her daughter, Denver, is haunted by the ghost of Sethe’s first daughter, who died violently by Sethe’s hand, her throat cut by a handsaw, eighteen years before the opening of the novel. Her daughter is unnamed except for the only word Sethe had had carved into her headstone: “Beloved”; not even ‘Dearly beloved’ because that single word alone cost Sethe twenty minutes of prostituting herself to the engraver among the headstones while his son watched, and she simply didn’t think to ask in the middle of it all.

Beloved was two years old when Sethe killed her, and now, eighteen years later she is a malevolent spirit haunting them at 124. Strange lights appear in the house, furniture is thrown violently about. Even the dog, Here Boy, is thrown hard enough against a wall to dislodge his eye. It is only when Paul D, a negro from Sethe’s past who also worked at Sweet Home with her, comes to live with them, that the haunting stops. Paul D challenges the ghost to fight him, curses it and throws back the table, and the ghost disappears.

This is all in the opening pages of the novel. Morrison’s prose is precise and nothing is wasted. Yet the central incidents of the novel – the death of Beloved, Sethe’s escape from Sweet Home, her relationship with Baby Sugg, her mother-in-law, the disappearance of Halle, Sethe’s husband, during the escape, and the birth of Denver during Sethe’s escape – are returned to again and again, each time circling to build upon details and nuance their import. The story is told from multiple perspectives, mostly in third person, but Morrison has characters tell their own stories, too, mostly to other characters, with varying degrees of accuracy, as well as three key monologues. Most of the tales are told to Denver about the past, and to Beloved, returned from the dead, now a woman at the age she would have been had she not died: about twenty. Beloved knows details of the past that Denver does not, that her mother has never mentioned, like the earrings given Sethe for her wedding by Mrs Garner, wife of their former owner. No one seriously questions the provenance of this strange woman who demands stories and hungrily consumes Sethe’s time, although Sethe wonders at one point whether she may be an escaped slave who has suffered sexual abuse. But everyone seems to accept the reality of ghosts. It is the nature of the book. Even Paul D, who hopes to settle at 124 after long years of wandering, but challenges Beloved as he did when she was incorporeal. He feels threatened by her presence.

It’s a strange premise but Morrison is skilled and her writing immediately overcame my own prejudices against stories of the supernatural. And really, to continue to be hung up on this aspect of the novel is pointless. Morrison fixes her narrative within the context of the post-Civil War era as negroes try to adjust to their new lives which are not always ideal. The supernatural elements are not gratuitous. Instead, they contextualise the characters’ experience and the history of the period within a mythic environment that speaks to the wider issues of slavery and racism. When four horsemen arrive, including the schoolteacher from Sweet Home to recapture Sethe, we understand the apocalyptic pretension. And Sethe’s obsessing over the milk that was taken away from her – milk for her child – not only highlights the tenuous nature of life for the slave, but transforms Sethe into the archetypal mother. Motherhood, itself, has a tenuous status in this novel. Sethe was not fed by the milk of her own mother and the slave experience is one of systematic removal from families. Sethe’s experience of happiness and freedom when she initially arrives at 124 is brief, only 28 days before the four horsemen arrive, a number so specific as to recall the menstrual cycle and blood, coupled with her daughter’s brutal killing: “Sethe had had twenty-eight days – the travel of one whole moon – of unslaved life. From the pure clear stream of spit that the little girl dribbled into her face to her oily blood was twenty-eight days.” When Sethe next feeds Denver, Denver drinks her mother’s milk along with her sister’s blood, still fresh on Sethe’s breast, like a witness to the martyrdom of a Christian saint. Soon, Sethe's two sons, Howard and Buglar, will run away from fear of her. Slavery has corrupted the very notion of motherhood. Morrison’s prose is pitch perfect, the story both a personal tragedy and a profound representation of the dehumanising institution of slavery.

Morrison was inspired not just by the general history of slavery in America, but by the story of Margaret Garner, whom Mr and Mrs Garner, Sethe’s owners at Sweet Home, are presumably named after in Morrison’s novel. Margaret Garner had escaped with her children, husband and other family across the frozen Ohio River in 1856 (recalling the escape of Eliza, a kind of literary predecessor, who famously escapes across the same frozen river in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published 1852). Garner killed her two-year-old daughter and attempted to kill her other children and herself rather than be recaptured and sent back into slavery when slave catchers surrounded the property her family was staying at. Her trial raised a challenge against the Fugitive Slave Laws which allowed escaped slaves caught in free states to be returned to their owners in the South. Morrison uses Garner as the kernel of her character, offering Sethe as an imaginative recreation. Through her, Morrison tells us, she sought to, “relate her history to contemporary issues about freedom, responsibility, and women’s ‘place.’ […] The heroine would represent the unapologetic acceptance of shame and terror; assume the consequences of choosing infanticide; claim her own freedom.”

At one point in the story Denver witnesses her kneeling mother being embraced by a ghostly dress as she prays. Sethe explains to Denver that it may be a ‘rememory’, like a vision of the past. Rememories exist in places and in objects that can be triggered in the mind. Sethe tells Denver that rememories exist beyond their initial physical circumstance, so that even, “If a house burns down, it’s gone, but the place – the picture of it – stays, and not just in my rememory, but out there, in the world.” Beloved, herself, is like a ‘rememory’ imposing itself upon the reality of the present.

It’s an interesting concept since it ties its contemporary readership to Morrison’s historical subject: that contemporary America has this past that continues to act as a social fault line. The novel, itself, is like a site of rememory, documenting the original American sin of slavery. But the concept also suggests why the characters in this novel tell each other stories and eventually relate their histories through their extended monologues. Denver constantly demands the story of her own birth be told – how Sethe gave birth while escaping with the help of a white girl, Amy – and when Beloved appears in their lives Amy relates the event to her with extra added details that Denver could only have imagined. Yet there is agency in these narratives – of the freedom to own the story of your life and thereby create a sense of self. Being a slave is the antithesis of this.

Morrison’s approach recognises that slavery denied physical freedom, choice and self-determination, and was an existential threat against the humanity and identity of slaves. The experience of Baby Suggs, Sethe’s mother-in-law, informs Sethe’s own attitude as a mother against slavery. Halle, Baby Sugg’s son married to Sethe, is the last of her eight children. Baby Sugg’s experience is of misery and loss. Except for Halle, all her children have either died or been traded as property. Her own freedom has been bought by her son, seemingly as a gesture of humanity by the Garner’s who are more enlightened slave owners, but she is old and now worth little, while her life has been bought at a high price, at the cost of her son and his family’s future freedom. And even with the cushioning experience of life provided by enlightened slave owners like the Garners – Paul D and other negroes on his property are encouraged to act with morality and think of themselves as men rather than ‘boys’ – havens like Sweet Home are shown to be an illusion. When Mr Garner dies his brother-in-law, the Schoolteacher, and his nephews come to the property at Mrs Garner’s request, with an entirely different set of principles. His pupils are encouraged to learn the human and animal qualities of negroes, and every small liberty accorded to them by Mr Garner in the past is removed. Paul D, relates the same sense of his own dehumanisation, recalling that his pretensions to being a ‘man’ encouraged by Garner were erased by the Schoolteacher when he was fitted with a bit:

“Mister [a rooster] was allowed to be and stay what he was. But I wasn’t allowed to be and stay what I was. Even if you cooked him you’d be cooking a rooster named Mister. But wasn’t no way I’d ever be Paul D again, living or dead. Schoolteacher changed me. I was something else and that something else was less than a chicken sitting in the sun on a tub.”

Slavery does more than remove the freedom of movement and self-determination while enforcing labour: its tenets are the basis to suppress humanity and identity, which exceeds the needs of labour, alone. Guns and whips may force labour from the individual, but suppressing identity and humanity is a means to suppress the will and spirit of an entire race.

This is why Morrison’s treatment of Sethe’s decision to kill her child is so remarkable. Sethe’s act is grotesque and she is shunned by her community when she is released. No one will come to 124. Sethe blames the malevolent spirit, but Denver blames the horror caused by Sethe’s act. Yet in the context of slavery, of the capricious treatment of slaves and their status as something-less-than-human, Sethe’s act is set against the institution, itself. In that context, it is not the act of a monster or criminal, but an act of love by a mother. Like her historical antecedent, Sethe refuses to allow her daughter to be turned over to a life of slavery. So, killing her child is also an act of rebellion: of refusing to allow white society to define her daughter’s fate or identity, for “anybody white could take your whole self for anything that came to mind. Not just work, kill, or maim you, but dirty you.”

Morrison’s novel has a gripping narrative that quickly draws you into the essential elements of the story. But Morrison is not content to draw us into a dramatic plot, alone. The story circles about, building our understanding of each incident, our attention spiralling into the psychological worlds of its characters, as stories are told with ever more intimate detail and insight. When Beloved returns to Sethe and Denver as a flesh and blood being, her presence is strange and unsettling, offering the hope of redemption for Sethe for her crime, but also the possibility of self-destruction. Yet Beloved’s story is also the sad story of slavery, itself. With no real epitaph on her headstone and only an adopted name, she represents the lives lost to slavery of anonymous millions: “Disremembered and unaccounted for, she cannot be lost because no one is looking for her, and even if they were, how can they call her if they don’t know her name?” The climax is not the work of a thriller writer, but a great craftsman. Nevertheless, it is a moment of great drama and breath-taking import, like reading something from Revelation: like Milton’s Satan rising from the lake of fire; like Yeat’s beast slouching towards Bethlehem to be born.

Beloved is a remarkable and powerful book.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!