I was nearing the end of Autumn yesterday morning when the news came through that George Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo had won the Man Booker Prize for 2017. It’s a book I have set aside for a read later on. I had made a tentative prediction to friends that Saunders’s book would win, based upon what I had been hearing about it. But Autumn was only the third of the Booker shortlist I had read. As I neared the end I thought that if I had had to make a choice of the three contenders I had read (Exit West, Elmet and now Autumn) Autumn would likely have been my choice for the Booker.

The buzz around Autumn has been about its contemporaneity. Apparently, Smith wrote it within a few months and it was published at speed so that events that form the backdrop of the novel, centred around the Brexit vote in 2016, still dominated the political landscape as the book was published. Early readers found that their lives were only just catching up to periods portrayed in the novel as they read. The book has been widely touted as the first post-Brexit novel.

However, while the backdrop of the novel is based on contemporary politics, the novel remains an intensely personal story, told from the perspective of Elisabeth Demand, an art lecturer inspired to her profession by a longstanding relationship with Daniel Gluck, a former neighbour and now surrogate grandfather, whose early mentoring of Elisabeth challenged her intellectually. The story begins with Daniel, now a hundred and ten years old, dying in hospital. Elisabeth, who hasn’t seen Daniel in years, makes contact with him again and begins visiting him. It’s worth noting that a minor detail of this arrangement begins with Elisabeth tricking hospital staff into allowing her to see him on the pretext that she is his granddaughter. At so many points in the story there is a significance placed upon the tensions between one’s humanity and individual’s identity in conflict with broader notions of identity.

It’s a point worth focussing upon, because there is a need to consider what Smith has tried to achieve here. One reviewer suggests that the story encourages us all to live each moment to its fullest, because we never know how long we have. And that seems like a good reading of the story. Certainly, the real-life story of Pauline Boty, a Pop Artist of the 1960s – once the object of Daniel’s unrequited desire – who died from a tumour because she refused treatment to protect her unborn child – exemplifies the sentiment. Boty’s work was forgotten for three decades, but her intellectual insights and her creative talent (along with Daniel’s unnamed sister) form the basis of Daniel’s intellectual development and the insights he passes on to the impressionable Elisabeth when he meets her as a child, seeking to interview him for a school assignment.

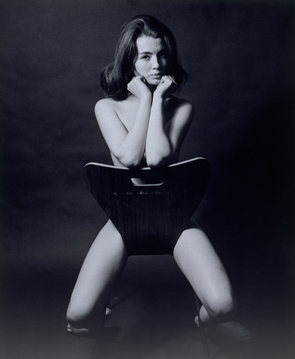

But Daniel’s recollections of Boty and Elisabeth’s subsequent investigations into her life (Elisabeth changes the subject of her university dissertation to Boty’s work) exists in the wider context of the Brexit vote, along with the 1963 scandal around Christine Keeler, whose relationship with the British Secretary of State for War, John Profumo, and her alleged relationship with a Russian naval attaché, raised concerns for national security. Keeler was a young model and was famously photographed by Lewis Morley to promote a never-to-be-made movie of the affair. The story of Elisabeth paying frequent visits to Daniel is set against her own personal history and her story of her growing up under Daniel’s influence, his own connection to Boty, and her subsequent interest in Keeler as a subject. Along with this is the current history playing out in British society, as houses are graffitied with xenophobic slurs – GO HOME – while others bemoan the rising inhumanity against humanity, like child refugees, now forced to reside in adult internment camps.

What is happening here? Is this really just an exhortation to live life to the fullest? I think a significant scene happens near the beginning of the novel in which Elisabeth decides to apply for a new passport. She has no plans to travel anywhere, although the officials who interview her assume she must have if she wants the passport. But Elisabeth’s application seems tied to the idea of identity, politically more tenuous since the vote. When she eventually gets the passport she will note with some irony that it is still a European passport. Yet to apply for the passport she must undergo bureaucratic checks that implicitly question the notion of personal identity, because a passport, after all, is a credential that has one function – to establish who you really are. Challenged by postal officials to get her photograph right – her head is too small, her hair is over her face – Elisabeth’s application becomes a farcical insight into the problem of identity. Officially, the passport and its photograph of her stand in place of her true identity.

It’s a problem the novel alludes to throughout. Daniel’s ideas are derivative, no matter how insightful he may at first appear to the young Elisabeth, Boty’s copying of the Keeler portrait invests it with new popular connotations beyond the original, and national identity subsumes individual identity to the point where some can put aside their own humanity and deny it to others. Over and over, the personal reflects the social and the social reflects the personal, like Elisabeth’s mother when she encourages Elisabeth to fake her answers for the teacher-imposed assignment of interviewing a neighbour, then bemoans the fakeness of news broadcasts. Then there is also the idea of female identity, raised through the story of Keeler, Boty and Elisabeth's connection with the artist's work.

While the novel has been hailed as the first post-brexit novel, it speaks on a person level through a very personal story. And while it is noted for its contemporaneity, the story is more complexly realised than a mere contemporary account would achieve. The story delves back into the protagonist’s past, Daniel’s past, past political scandal, it references art and art theory, and is literary in its referencing of other texts like Shakespeare’s The Tempest and Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities, as though the story itself is a metaphor for the complexity and meaning which the simplicity of a nationalistic vote might implicitly be deemed to deny. In so doing this Smith manages to convey the import of this historic moment. She has Elisabeth read A Tale of Two Cities to Daniel while he lies dormant in hospital, but Smith has referenced the novel several times already in a parody of Dickens’s opening paragraph. It was the worst of times, it was the worst of times

, the novel begins, and later continues:

All across the country, people felt it was the wrong thing. All across the country, people felt it was the right thing. All across the country, people felt they’d really lost. All across the country, people felt they’d really won. All across the country, people felt they’d done the right thing and other people had done the wrong thing. All across the country, people looked up Google: what is EU? All across the country, people looked up Google: move to Scotland. All across the country, people looked up Google: Irish passport applications. . .

Smith’s tableau is personal, but her backdrop is large and historic. Dickens portrayed the insanities of the French Revolution – its promises of a better world and the terrible violence it inspired. Smith is portraying a moment of social upheaval too, in which the ideals that are driving English society are understood, but the outcomes are still largely unknown. This is a simple book to read, but it is complex and layered as well. There is so much to talk about here, so much a review of this length can’t cover, and shouldn’t, given that the book should speak for itself. I would highly recommend this book.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!