I've been on a bit of a murder mystery roll lately, with discovering a fun new cosy murder series to indulge in. Bikerbuddy & I had a discussion about it, with him questioning me on just what it is that I find appealing in these stories, and in the so-called Golden Age detective stories generally (Agatha Christie, Dorothy L Sayers & Ngaio Marsh are all long favourites of mine). The best I could answer was the feeling of the worlds created by these writers, the stable, well ordered worlds where the story will progress in an orderly way and where eventually the villain will be unmasked and everyone will return to a peaceful life. To me these books are the perfect way to escape from a stressful day and relax. And of course, I like trying to see if I can spot the clues and figure out the murder before the reveal in the second last chapter.

The last third of this book is devoted to the writers and writings of the Golden Age. And it comes to much the same conclusion as we had a few weeks earlier, that the appeal of these books was in the safe ordered world they created. And places them in the context that I hadn't really considered - the Golden Age was the time between World War I and World War II. As Worsely reminds us:

Even beyond the annual commemoration of Remembrance Day, the lasting effects of the Great War could not be ignored or avoided. Children were left orphaned, the surviving young men were left wounded in ways both seen and unseen, young women left without partners. This was the background that should be born in mind when the Golden Age writers are criticized - as they often are - for being limited or sterile or boring. They were writing not to challenge society or to stir things up. They were using their pens to heal. (p.227-228)

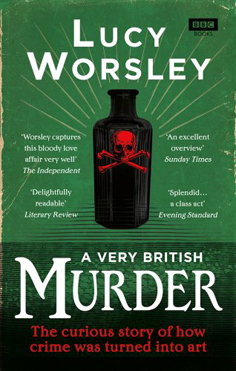

Of course I'm jumping in at the end of this book. It isn't solely about the rise and fall of the Golden Age, it takes us way back to the early 1800s, to when people began to take pleasure in murder. The book begins with Thomas De Quincey, who, in 1827, published a humorous essay called 'On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts'. De Quincey identifies the reporting of a horrific series of murders in east London in 1811, the Ratcliffe Highways murders, as the starting point to people looking upon murder to provide entertainment.

A Very British Murder takes us through the Ratcliffe Highway murders, describing the rapidly changing world in which they took place as a time of great upheaval and uncertainty.

The future George IV had just become the regent with his father's growing madness, slaves were revolting in the US and Luddites were violently protesting in the Midlands. The city was crowded with people seeking a better life in London, people who no longer knew their neighbours as they had in the country, the streets were dark and crowded, and people were afraid. The case became the first serious crime to be widely reported in the media, and gave rise to a new genre of journalism - murder reporting, with all its inaccuracies, gory details and outright condemnation of everyone and everything seeming to stand in the way of a speedy conclusion.

The book then continues through time to 1946, when George Orwell published an essay lamenting 'The Decline of English Murder’. It takes us through changes in society and in public taste, through the major murders of each era, and the stories which drew inspiration from these murders. In each era we get an insight into the reading tastes of the time, and of the writers such as Dickens, Collins, Braddon and Conan Doyle who were able to capture the changing tastes of the public in their writing. We progress through gothic horror to penny blacks to penny-dreadfuls, into sensation novels and finally to the rise of detectives such as Holmes. And then finally to the Golden Age.

Apart from the growing public interest in all the gory details of murders, the book has some insights on the growing literacy levels of the working class, and the increased educational opportunities. By the 1840s, 60% of people were able to sign their own names in parish registers when getting married. And at this time, reading was taught before writing, so the percentage of people able to read was higher. And the growing number of literate people wanted to read about murders, the gorier the better. In a chapter on the seeming contradiction between a Victorian society growing increasingly respectable and prim, and the unabashed pleasure that they took in murder, Worsley reminds us:

The Victorians shared a love of violence and blood with their Georgians grandparents, equally avid attenders of boxing matches and public hangings. And indeed, the Victorians might well have found something very familiar in our own modern obsession with brutal horror films and violent computer games. This pleasure taken in violence is timeless, it just takes different forms and emphases depending on the technologies and economy of an age. In the nineteenth century, the rise in literacy and the fall of the price of print allowed a love of blood to flourish in new ways. But it was always there - and still is today.

Overall this was an entertaining and informative look at the development of murder stories as a form of entertainment. Worth reading by any mystery fan.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!