The back cover of my copy of this novel says, This thrilling, high-speed story starts in one way and then takes you someplace else.

The impression given by the first release of the book suggests action and adventure. We’re told, Irene Bobs loves fast driving

, which seems to qualify her for the brutal race

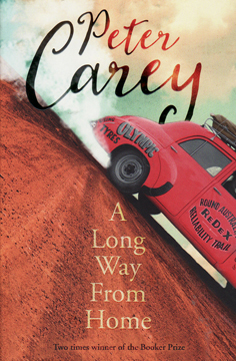

. The cover has a picture of an old Holden with racing decals, supposedly from the Redex endurance trial of 1954, which is the central conceit of this book, kicking up dirt. It all seems exciting, but it made me wonder whether there would be something superficial about this book, which was not what I had come to expect from other novels by Carey over the years. Carey has specialised in misfits, not heroes, from the macabre gothic romance of Oscar and Lucinda to the postmodern and highly bizarre Tristan Smith. And ever since The Tax Inspector I have been attuned, when reading Carey, to notice births in his stories. The horrific birth at the end of The Tax Inspector alerted me to Carey’s birth motif, often suggesting the burdensome legacy of our beginnings; not only our birth but the formative experience of our growing up. My impression has been that Carey is concerned with the maltreated and the marginalised in his writing.

Which brings us to this book. There are other hints on the back cover that suggest the book is more than a superficial race story: … [the] novel reminds us how Europeans took possession of a timeless culture

; the consequences of the age of empires.

It’s a bit odd, as though the publisher wasn’t quite sure how to sell this book. And these later claims seems rather large as one settles into the first quarter of the book which concerns itself mostly with the domestic affairs of Titch and Irene Bobs and their Neighbour Willie Brachhuber. Titch and Irene own a car dealership and are looking to become Ford representatives, or Holden if they can’t get Ford. They’re not hopeful, and Irene enters them into the Redex Endurance Race hoping to monetise the little fame they might win from participating. Meanwhile, Willie Bachhuber, the local school teacher in Bacchus Marsh, is facing his own problems. He has the court after him for arrears in child payments for a child he is fairly certain is not his. And while he is usually a calm man, he is about to lose his job as a school teacher for hanging a child out a window, upside down. His lack of options and Irene’s need for a navigator set the stage for the race.

The title, A Long Way From Home, reflects central issues that this novel addresses: what constitutes the self and identity; how does a place and its stories help define an individual; and, how do we define an understanding of home? Carey, himself, now lives in New York, but with few exceptions (eg. Olivier and Parrot in America) his novels are set in Australia and deal with Australian themes. A Long Way From Home is initially set in Bacchus Marsh where Carey himself grew up, and in the later part of the novel it is upon Bacchus Marsh which Willie fixates as home and his final destination in his long trip around Australia, even though by leaving Bacchus Marsh he has been drawn closer and closer to a sense of who he truly is.

What makes this novel important from a national perspective is that by returning to the mid-50s Carey is able to examine much of what has defined an Australian identity, too. Willie implicitly shares the uncomfortable associations of the all-too-recent history of Nazism through the heritage of his German name. But it is a similar association through which the reader is also culpable, since Carey is not afraid to call much of Australian history by what it was: racial cleansing and repression. By drawing his reader further and further from the comforts of fifties conservativism and of Eurocentric views, and by offering a glimpse of a wider, deeper Australian culture, Carey’s book has become another marker in what John Howard, our conservative former Prime Minister, pejoratively called a black armband view of history. But works like this are necessary to refute some of the fictions – fictions which Carey addresses in his book – maintained to justify that history and treatment.

I initially found the progression of the plot jarring, as it took some time for Carey to reveal why the Redex race was necessary to his story, and then when that was done, the plot seemed to be this strange hybrid novel, as I have suggested. It seemed to move from a conservative nostalgia for the simpler times of the fifties to a more difficult and confronting text about national identity and history, closer to issues currently reflected in the national debate. Saying this makes the novel seem difficult and abstract. It’s not. The story itself is an abstraction of the issues, true, but it works well at the level of a plot about very real characters.

Of course, a fair question to raise about a novel like this is whether it employs a paternalistic voice of a privileged white man writing about Aboriginal issues. One aspect of the novel that ameliorates this problem is that Carey gives Aboriginal characters their own voice and their own perspective of Australia and its history, some of which have no similarity to white historical accounts. Carey is able to offer an Aboriginal perspective that asserts a moral rather than a factual truth, much like the stories of Paddy Roe, told to the anthropologist Stephen Muecke, in a melding of traditional Aboriginal story techniques and modern subjects. Charley, an Aboriginal boy, for instance, gives an account of Captain Cook which has many historical inaccuracies, no matter what your ideological position on these matters. But in reproducing this account and other rewritings of the accounts of white colonialism, a moral truth is asserted in the story:

What may seem to be the signs of madness might be understood by someone familiar with alchemical literature as an encryption whose function is to insist that our mother country is a foreign land whose language we have not yet earned the right to speak.

The idea that Australia remains remote and foreign to the vast majority of its inhabitants is an interesting facet in Carey’s deliberation upon home and identity. In that sense it is also a story by a white man about white people and their own relationship to the landscape of Australia. In this story, as in others, there is a birth which is important to the plot. But Carey also delves back as far as living memory, at least, to consider the formulation of a national character and attitudes. This is a deceptively simple story that has resonances of Australia’s past and present political debates about culture and identity. That Carey can start with the story of the Bobs and Willie Bachhuber in the Redex Race and transform it into something of national import shows yet again that he is one of the great writers not only of Australian fiction, but one of the world’s great writers.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!