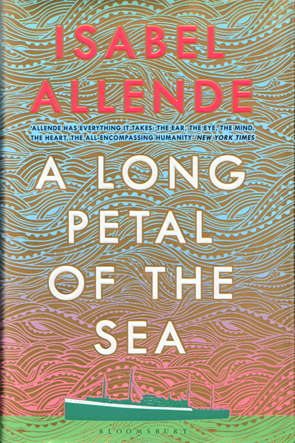

I’ve never read Isabel Allende before, so I have little to compare her latest book to. In her author biography Allende describes herself as a novelist, feminist and philanthropist

. She also has a reputation as a South American magic realist writer, with books like House of Spirits, which made her reputation in the 1980s. In fact, it was the constant recommendation of that book by a work colleague that drew me to Allende’s latest novel, A Long Petal of the Sea, published earlier this year. A Long Petal of the Sea is not magic realism, however. Allende draws directly from history and admits that she has based her fictional characters upon real people whom she has known and interviewed. In fact, the book at times feels like a non-fiction account.

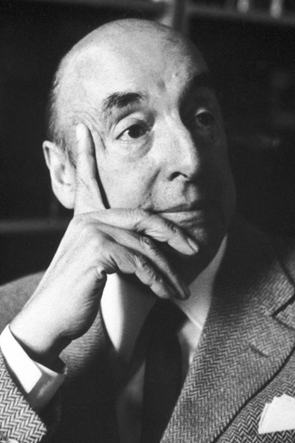

The title, itself, as magical as it may sound, refers to the long, thin country of Chile on the Western coast of South America. It’s taken from a line of poetry from one of Chile’s foremost poets, Pablo Neruda. Extracts from Neruda’s poetry form epigraphs to each chapter as well. As much as the book may appear to be a novel about characters, it is also about Chile and the impact of fascism on people in the twentieth century. The novel spans over half the century, shaping the story around the history of two dictatorships through the guise of a family saga. The novel begins in Spain, 1938, with General Franco’s Nationalist forces fighting Republican soldiers attempting to resist the inevitable. Victor Dalmau is a young medical assistant in the Spanish Civil war. His brother, Guillam, is a soldier in the conflict. Roser Bruguera, a young music student of their father’s, shows prodigious talent. She becomes Guillam’s lover and eventually falls pregnant to him before Guillam is killed during combat. When the Republican forces are defeated by General Franco’s army, Roser and Victor’s mother, Carme, join Victor’s friend, Aitor Ibarra. Along with thousands of others, they attempt to cross into France. But the borders are closed and the refugees are left, starving and exposed.

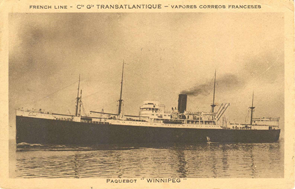

From here the novel shapes the story into a broad history of the plight of the Spanish refugees. Pablo Neruda persuades the Chilean government to accept two thousand Spanish refugees for resettlement. He acquires an old French cargo ship, the Winnipeg, and refits it to transport the Spanish refugees whom he hopes will help revitalise his country’s culture, industry and intellectual life. Victor, feeling responsible for Roser and his nephew, and out of a sense of duty to his brother, feels it imperative he help Roser escape to Chile, too. But for her to be accepted on board the Winnipeg, Roser must be a family member. They have no choice but to marry. Thus begins Victor and Roser’s long marriage, born not from passion or love, but from necessity. Neither at first wish to sleep together, both believing they will divorce once they arrive in Chile. But Chile does not allow divorce. So their lives together become a history of other lovers and the complications that that entails, before a long reconciliation to a deep love with one another is achieved.

Eventually, Chile also succumbs to right-wing fascism with a coup by a military junta led by four generals, the most famous being Augusto Pinochet. Once again, Victor and Roser feel themselves in the grip of history. This time, they are forced to flee to Venezuela, a stable and rich South American country, where they hope to outwait Pinochet’s regime and then return to Chile, which they have come to think of as their real home.

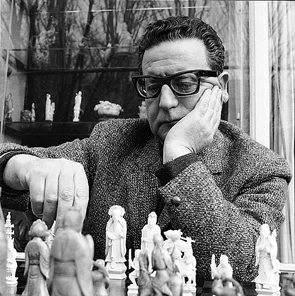

Allende’s novel recounts much of the playbook of twentieth century history: war, concentration camps, torture, refugees and flight, to hope for a better future and the slow movement towards more liberal societies. Allende’s characters are worthy of our interest. Roser is an accomplished pianist and is accepted readily by Chilean cultural elites. Victor becomes a skilled surgeon and teaches medicine, but he also befriends Chile’s president Allende, placing him close to the nation’s own unfolding dramas. The president and Victor have a common love of chess. In real life, Isabel Allende was god daughter to President Salvador Allende, so her personal interest in the history is understandable. She based her character, Victor, upon a real Victor who played chess with Allende, and like her characters, she herself moved to Venezuela during Pinochet’s regime. In her acknowledgements page, Allende writes, This book wrote itself, as if it had been dictated to me.

Allende’s statement speaks of the personal connection she has with the material, which accounts for the book’s insights into the psychology of the Spanish refugees and the impact of fascism. It also accounts for a complex and rich web of characters whose families make connections, within which secrets are held and the understanding of how long-term acceptance of change and adaptation is made. However, it is also a weak point in the narrative, too. The most compelling aspects of the story occur in the first half: how Victor massages an exposed heart back to life in a field hospital; of the desperate flight to the French border and the momentous decisions made to ensure survival. The sense that history has almost been dictated

to Allende is felt most acutely in the second half of the book, which has nothing quite as dramatic as the first. As the story matures in its latter third, the long timeline Allende has chosen makes it difficult for her to maintain tension in the story. The events of a decade become compressed within a chapter, like a summing up and rush towards the end. Until the final chapter, when Victor learns more of his family’s history, the characters begin to feel like props for the historical narrative Allende is most interested in. When Roser and Victor return to Chile from Venezuela after the end of Pinochet’s regime, Victor begins voluntary work in shanty town hospital to alleviate his sense of guilt at having to take work in a commercial hospital. It provides an opportunity to describe the conditions of people in the shanty towns – Victor, after all, would not see them otherwise – and the governments treatment of these people, but the digression seems less in the service of the story and more in the interests of documenting the social history of Chile. In short, the characters sometimes seem to take a backseat to what is non-fiction, rather than fully inhabiting a story of their own within the historical context.

That is not to say that there isn’t a lot happening with the characters in this novel. The character line-up is more rounded than I have suggested – the del Solar family and their patriarch, Isidro del Solar, with his conservative politics – provide a counterpoint to Victor’s experience, for instance, as well as the opportunity for forbidden love. There is a bit of that happening in this book. But with the historical context of their lives being what it is, there is a strong sense in the narrative about the need for humanity. Allende’s story is a compassionate retelling of the impacts of fascism on ordinary people. While passion may rule our lives from time to time, much like the ruptures of history, it is long term love, quiet and accepting, that is the most important driving force, like a counterpoint to history. Victor and Roser have the patience to endure the vicissitudes of history while never losing sight of the ideals and hopes that shape their lives; a belief in decency, the need for purpose and genuine connection with others. While this novel gives shape and form to aspects of twentieth-century history, it is also about endurance and human nature, too.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter