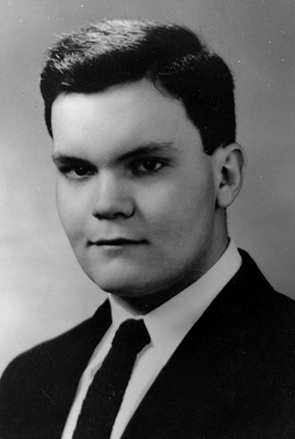

A Confederacy of Dunces won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1981. However, the novel was written in the 1960s and its journey to publication is a long history and an interesting story in itself. I mention this at the start of this review because the short forward to the novel by Walker Percy foregrounds the circumstances of its publication as well as the sad end of its author – John Kennedy Toole committed suicide after several attempts to publish the book – and his mother’s long efforts to have it published posthumously.

Barthes’ essay, ‘The Death of the Author’, published in 1967 (a date roughly roughly analogous to the period Toole was attempting to publish his book) eschews the idea that an author’s life or intentions might serve to understand or approach a text. But I am not an academic writer, and given Percy’s foregrounding of Toole’s personal story I am inclined to explore Toole’s life briefly in connection with his creation. Because, as I read A Confederacy of Dunces my interest in Toole was piqued by his gargantuan protagonist. In short, I found it difficult to separate my curiosity about Toole from the story of Ignatius Reilly. This enormous and ballooning character, unemployed, holding an advanced degree, a man of around thirty who constantly wears a green hunting cap with green ear flaps, with blue and yellow eyes, who pens his social diatribes in his bedroom which no-one is ever likely to want to read, and lives with his long-suffering mother, Irene, is a figure who existed, as I read, outside the pages of the novel: he seemed entirely real. Walker Percy had planted a seed in my mind, that Ignatius Reilly, as much as I knew it was naïve to think so, was somehow an avatar of his creator. I had the bare facts in my hands. Toole sounded like a loner, a highly intelligent and creative man who others didn’t get, who lived with his mother – a strong and determined person according to Percy’s account of her, virtually forcing her son’s manuscript on him to read – whom I imagined dominated Toole’s life. I read more about his life after I finished the novel, and found that some of my impressions seem supported. But Toole was obviously more complex and had conformed to social expectations more than Ignatius. Yes, Toole also had advanced degrees, for instance, but he had also taught at universities and had served in the army as an education officer.

Yet there were other aspects of Toole’s protagonist which seemed to align with Toole, himself. It turns out that Toole had worked for a clothing manufacturer with similar problems to his fictional Levy Pants where Ignatius briefly works, and he also filled in as a hot tamale cart vendor for a friend at one stage, similar to Ignatius’ job as a hot dog vendor, pushing a hot dog cart around the streets of New Orleans and eating more of the product than he sells. There is even a sense that a traumatic event is the catalyst for change, both for Ignatius and Toole. Miss Annie, Ignatius’ the long-suffering neighbour, tells the story of the death of Ignatius’ dog, and I remember thinking as I read that this was obviously significant to an understanding Ignatius’s character (Ignatius even masturbates to fantasies of his dog early in the novel). The dog’s death marks a change in Ignatius: he breaks with the church when his priest will not officiate for the dog’s burial, his relationship with his mother deteriorates, and Ignatius becomes withdrawn, rejecting the obvious sexual advances of Myrna Minkoff. Toole seems to have had his own turning point. When he was serving in the army a gay army instructor attempted suicide and Toole was criticised for not calling for help immediately – he was hoping the man would recover and avoid reprisal – and fell into depression. It was shortly after this that he began writing his novel and the gay community features heavily in some aspects of the plot.

But Ignatius, as much as I might wish to read him as a representation of Toole, is not Toole, even though some aspects of his life may be analogous. A more likely model for Ignatius is Bob Byrne, Toole’s English professor. Byrne is said to have been a slob like Ignatius, played the lute and wore a dear stalker hat. He and Toole discussed the writings of Boethius, a medieval philosopher who characterises the vicissitudes of life as a wheel of fortune, lifting people up or tearing them down according to the vagaries of fate. The concept is central in Ignatius’ thinking. Through his sloth, his lying and sheer defiance of norms, Ignatius blunders through a variety of situations for which he is largely responsible, yet denying responsibility, suggesting that in his mind his problems are to be attributed to others or life’s wheel, to which he is bound. Ignatius is a fabulist. He always sees himself as the victim, which is wonderfully characterised by his long-suffering “valve”, a part of his digestive tract which tends – so Ignatius claims – to shut completely when he is vexed or under pressure. Ignatius is highly educated, but he uses his education as a spear against others, and as a shield against the reality of his own personality; that he is lazy, sexually repressed and over-inflated with self-importance. He uses the fiction that he is writing an important intellectual tract – that he has purpose – to justify his inactivity and failure. Apart from his writing, his days are filled in by the cinema, usually so he may scoff and criticise the bourgeois preoccupations and ludicrous plots of movies, and his long, slothful indulgence. But when Ignatius is almost arrested by Patrolman Antonio Mancuso, merely for the sight of his corpulent presence at the Night of Joy club, a series of events are set in motion that will bring Ignatius more fully in contact with the world. When his mother crashes their car – Ignatius contributes to her distraction – she is bound to settle with a property owner but she cannot afford to pay. Suddenly, Ignatius must look for employment.

It’s interesting to note that while the publisher, Simon and Schuster, was interested in A Confederacy of Dunces in the 1960s, Toole was asked to rewrite, which he eventually declined to do. Robert Gottlieb wrote: “there must be a point to everything you have in the book, a real point, not just amusingness that's forced to figure itself out”; and finally, “it isn't really about anything.”

Of course, publishers can be wrong. There are many stories like this of books which are rejected only to eventually become classics: Dune and the Harry Potter Series come to mind. Yet A Confederacy of Dunces does cover a variety of topics, although it isn’t as single-mindedly focussed in its purpose as Catch-22, a book Gottlieb used as a comparison to make his point. Included in the panorama of Toole’s canvas are the following: Dunces touches upon the gay community of New Orleans in the 1960s, usually reviled and characterised through cliché by characters in the novel. Ignatius hits upon a mad scheme to undermine to levers of social power by installing homosexuals in all aspects of government and the military. If this seems weird, he also attempts to lead factory workers in a violent revolt against the management of the clothing company he works for. There is Ignatius’ college friend, Myrna Minkoff, who advocates sexual freedom and open sexuality as a panacea for a variety of society’s ills. Like Ignatius, she was subversive during their degree against their college professor, Dr Talc, and her ideology is critical of Middle Class values. There is the Levy’s, the family who own Levy pants, and their miserable marriage. Mrs Levy blames her husband for the business’s slow demise and his betrayal of his father’s legacy. Mr Levy prefers to remove himself from the business owing to his poor relationship with his father. And Mrs Levy’s long-term campaign to protect the job – and therefore the wellbeing – of ancient Miss Trixie from her husband’s office is wonderfully misguided and self-serving. At the Night of Joy bar we follow the comical relationship of its owner, Lana Lee, Jones, a black man she hires for exploitative wages to sweep her floors, and Darlene, employed to ply drinks to men at the bar, but whose dream is to be an exotic dancer with her parrot. Finally, there is Angelo Mancuso, the cop who first attempts to arrest Ignatius and is placed on duty in a public toilet with the warning that he faces unemployment if he fails to make an arrest soon.

The threads may seem disparate but they connect through a series of character relationships and a plot that seems to spiral towards a centre as the various elements of the story become entangled. Aspects of the book read like a Carry On film, but its absurd elements which tie neatly together in its denouement reminded me of the absurdities and wit of Restoration comedy. But it is not just that Toole manages to draw these threads together, giving cohesion to what reads like a picaresque story in which each of Ignatius’ failings or disasters, or the failings and disasters of various other characters, set the scene for the escalating absurdities within the plot. It’s that the book does seem to have “a point”.

Ignatius provides an ideological foundation for this, with his reaction to modernity, which is multi-faceted. His sense of the history of the moral progression of society is warped against Humanist principles which place responsibility upon the individual: “Merchants and charlatans gained control of Europe, calling their insidious gospel ‘The Enlightenment’.” He understands the story of Piers Plowman to be of a radical historical devolution towards the principals of modernity:

The Great Chain of Being had snapped like so many paper clips strung together by some drooling idiot; death, destruction, anarchy, progress, ambition, and self-improvement were to be Pier’s new fate. And a vicious fate it was to be: now he was faced with the perversion of having to GO TO WORK.

Rather than a liberating historical force, Humanist principles, the free market and Enlightenment thinking are threatening to Ignatius because they place responsibility upon the individual. While he may no longer attend church, he essentially believes in the traditions of the church and tenets of medieval society. His interest in Boethius and his Wheel of Fortune suggest Ignatius cannot accept his own agency in life, and he displaces personal responsibility upon fate itself, or those around him. Ignatius is critical of the Middle Class, including the Protestant work ethic, and sees effort as self-deluding. He is also critical of aspects of the Counter Culture, as embodied in the character of Myrna, with her open response to sexuality. Ignatius is out of step with his times and his self-delusion is the source of absurd comic moments throughout the story.

There are aspects of other characters’ stories which reflect upon the modern world Ignatius opposes. For instance, the story also satirises aspects of liberal society. Mrs Levy’s desire to support a cause, at least for as long as it amuses her, reveals her to be self-serving and vacuous. Her misguided attempts to ‘help’ Miss Trixie are no better than Ignatius’ misguided attempts to effect change, other than that his goals appear loftier or on a grander scale: his efforts to encourage workers in Levy Pants to revolt, or his hair-brained scheme to undermine society by installing homosexuals in key positions of power, are manifestations of his rage against the modern world. Ignatius’ sexual repression (“You know how I feel about touching other people”) also transforms Myrna, a young women he befriended at college, as an antagonist in his mind whose values he must work against or trump, even though it is clear he has some desire for her. Myrna’s politics advocate the sexual freedoms of the Counter Culture.

Other characters provide a counterpoint to Ignatius. Jones, the black man who works in Lana’s Night of Joy bar, cannot afford the luxury of inactivity. As a black man he knows he is in danger of being arrested for vagrancy if he has no employment. Angelo Mancuso, the cop, is willing to risk his health as he spends week after week freezing in a public toilet, hoping to protect his job. When Ignatius exhorts the factory workers he attempts to lead in an uprising to violence, they abandon him.

Yet, though we may understand that Ignatius is a flawed character and that his ideas are regressive, they attain a certain level of sympathy, too. His attitudes align with Jones’ plight, which highlights the continuing exploitation of Negroes in modern America of the 1960s. He is paid well below minimum wage and kept in check by his employer due to the institutional racism of the justice system. Ignatius’ writing shows an awareness of the situation of black workers, too, particularly of those employed by Levy Pants who he views as modern incarnations of “mechanized Negro slavery” which represents “progress the Negro has made from picking cotton to tailoring it.”

But Toole’s book ultimately seems regressive, its character defiantly out of touch with his milieu. The book may be about something, but it is strangely out of step with the progressive impulses of the 1960s. Maybe this is what Gottlieb was reacting to, that the resolution to the various problems raised within the plot are blithely solved, and there is the merest hint in the novel’s denouement that Ignatius’ ideological stance is a posture of self-defence and sexual repression. And while the novel may allude to progressive thinking towards black America, it may also reflect outdated attitudes: that it is a novel of its time.

To return to Toole, some aspects of the plot and its characters made me wonder whether Toole was gay. Some sources suggest he was a repressed homosexual, others don’t mention it, but account for several women he dated, even if the relationships may have been somewhat inhibited. I wasn’t sure whether Toole’s treatment of homosexuals reflects widespread contempt within society at the time he wrote the book, or whether he was being satirical. His characters use every derogatory term I think I am aware of against homosexuals, and Ignatius’ plan to install them in the military and government as an undermining strategy recalled to me prejudices against gay people serving in the military in past times. The gay characters remain frivolous, ridiculous and two dimensional. They tend only to want to party and dress up. Ignatius’ own fondness for a pirate suite and the plastic cutlass that accompanies it seem to suggest yet another level of ambiguity to Ignatius’ sexuality, but the contempt against homosexuality feels pointed at times, and I wondered whether this dates the book a little.

Nevertheless, A Confederacy of Dunces is a truly funny book. Its protagonist is outrageous and larger than life, both literally and figuratively. The plot weaves through a variety of subplots which are brought together in a satisfying way (if you have a penchant for the absurd and improbable, as I do, possibly less so if you desire something more realistic). Toole has a natural gift for comedy and he writes well. And even if you aren’t inclined to care what the book might be trying to say – Catch 22 was a book against war – it’s still an entertaining read, full of characters you may have a vague feeling that you have known. I am glad to have finally enjoyed it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!