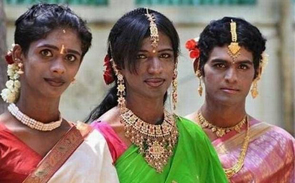

A Burning is Megha Majumdar’s first novel. It’s a well-executed tale of aspiration, of systemic corruption and the despair of poverty. The book is primarily the story of three people: Jivan, a young girl arrested in connection with the burning of a passenger train; Lovely, a hijra – a word denoting transgender or intersex people in Indian culture – who aspires to act in films and has been receiving lessons in English from Jivan; and PT Sir, Jivan’s former physical education teacher, who now hopes to rise through the ranks of the Jana Kalyan (Well-being for All) Party, under the mentorship of Bimala Pal, the party’s second in command.

A Burning is also a fairy tale of sorts; the story of remarkable success despite the odds. Yet the fairy tale has an odd sting to it, serving to highlight the hopeless situation of many poor people in India. In several scenes Jivan recalls either attending a birthday party in which good food was served, or other incidental meetings in which she was impressed with the wealth of others. But these people are not wealthy, she realises, just middle-class. It draws a stark contrast to her own life, living in the Kolabagum slum where her house has one room with two brick walls and two walls of tin and tarp […] behind a garbage dump

. The roof is not properly affixed and can be easily removed. When her family is to be evicted to make way for a coal mine, they have no other recourse than to save their own faeces and urine over the period of a week to make ‘bombs’, part of a vain attempt to deter their evictors. The message is clear. In the end, the poor have little more in the world other than their bodies and ingenuity. For every rare and remarkable escape from the slums there are millions who remain with little hope of achieving their dreams.

The terrorist attack upon the Kolabagan train is horrific. Most train attacks in India have been achieved by bombings or derailment since the early 1990s. But in this attack the train is firebombed and many are burned to death in the ensuing fire. Jivan, who is near the railway when the attack occurs, carrying books which she is using to help teach Lovely to read, is later accused of having carried kerosene and other combustibles to the scene. Even worse, she has responded to the incident on social media, giddy with excitement over the new phone she has saved for. When her first public post on Facebook fails to attract the attention she craves, she writes another:

If the police didn’t help ordinary people like you and me, if the police watched them die, doesn’t that mean [. . .] that the government is also a terrorist?

Added to this, one of her Facebook ‘friends’ turns out to have been linked to the attack. Jivan knows nothing of his background and had no prior knowledge, but she is soon arrested a few nights later.

Part of the power and popular appeal of this novel lies in its fast-paced story that switches between the three protagonists in a series of vignettes, mostly in short chapters, with only a few longer chapters that flesh out their changing fortunes. There is a filmic quality to the writing, cutting away to minor characters in occasional interludes, between the mostly-brief scenes that service each of the three main characters. All of this makes the book a fast read. Yet, despite the brevity of some of the chapters, each of the major characters is well realised. Jivan’s excitement at her new phone and her despair over her poverty, along with the precarious financial state of her family’s affairs are realistically portrayed. Also, Lovely’s naive dream to become an actress is both inspiring and painful. She faces prejudice against her class and sexuality with a strong sense of her own worth which makes her likeable and relatable. And PT Sir’s sense of inferiority as a physical education teacher is palpable. His mercenary desire to rise above his station is only occasionally punctuated by a sense that there are others who may have to suffer for him to succeed. It’s interesting that of the three main characters, his is the only story told in third person.

Equally well delineated are the moral positions represented by each of the three characters. Jivan, on trial for terrorism, is entirely innocent. Her appeal to Lovely to testify on her behalf and the expectation that her former teacher might speak for her character is entirely reasonable. But moral obligations are shaky in a world in which compromise can be traded for success. The irony of Lovely succeeding as a result of a social media post while Jivan languishes in prison after her own first public foray into social media is stark. But while we don’t begrudge Lovely her success, PT Sir is evidently a lacklustre teacher whose rise through the party ranks, in part based upon his reputation of having been an educator, is self-serving. Meanwhile, Jivan desires to be a teacher of the poor, serving anywhere in India, yet she languishes in prison. The machinations of the system – a system corrupt enough to encourage false testimonies from men like PT Sir out of expedience – also highlights the ironies of poverty and systemic corruption in India. Jivan is literally forced into a underground, into a basement cell with no natural sunlight, while PT Sir moves upward

as his elevator takes him to his new office.

Majumdar’s narrative also includes the problems of religion and sexuality as part of the struggle of ordinary Indian’s to realise their ambitions. For Muslims, the threat of religious reprisals becomes evident in some dramatic scenes, and Lovely’s status as a hijra places her in an unusual in-between state in Hindu culture. Hijras are thought to have a connection to God and are often paid to bless babies and weddings. But attitudes to hijras changed in the nineteenth century as British moral values affected traditional Hindu culture. As a result, hijras are both worshipped and reviled. Mrs Debnath, the wife of Lovely’s acting teacher, does not want her in the house.

Ultimately, A Burning is a fairly bleak novel that seems to offer little choice other than either to embrace the system and its corruptions or be destroyed by it. It is a cynical dichotomy, even if somewhat realistic, that is dramatized in the plight of Jivan. The system can either treat her fairly or not. Society, through its access to social media, is left with the same choices, while Jivan’s reliance on her former teacher and friend is equally predicated on a system that also has them caught. While none of this sounds salutary, there is a grim sense in the closing lines of the novel that we have read something real and enlightening.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!