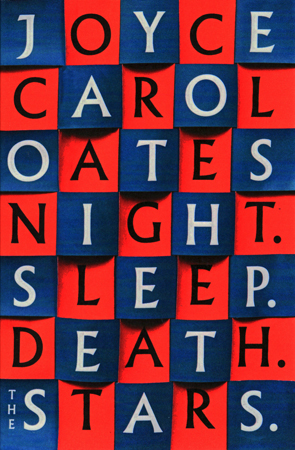

- Category:Fiction (General)

- Date Read:13 October 2020

- Pages:787

- Published:2020

It’s natural to compare any new book you read by an author you’ve previously read to earlier books in their oeuvre. When it comes to Joyce Carol Oates, I’ve previously read A Book of American Martyrs and Hazards of Time Travel. Anyone who is familiar at all with Oates will realise I have read pitifully little of her work. By my count, Night. Sleep. Death. The Stars. is Oates’ 59th novel. That doesn’t include her further prolific contribution to short fiction and non-fiction.

But my sparse reading of Oates didn’t prevent me coming to this book with certain expectations. The Prologue is dramatic, recalling for me the explosive opening of A Book of American Martyrs. John Earle McClaren, otherwise known as ‘Whitey’ for his white hair, witnesses a man being assaulted by police by the side of the road. Dr. Azim Murthy, a medical doctor of Indian descent, has been mistaken for a negro and pulled over. The police seem annoyed at their mistake. He is searched for drugs, anyway, and treated to an abusive tirade. The police will later allege that Dr Murthy exhibited threatening behaviour, but the fact is that their behaviour has been so unnecessarily aggressive, Murthy has been stupefied and confused by them. Unable to follow their directions, they decide to ‘light him up’ with several blasts from a taser. Whitey, a mayor of Hammond twenty years ago, stops to intervene. As he approaches the police, they consider he is a threat, possibly in cahoots with their Indian victim. So, they light Whitey up too, over and over, until their assault precipitates a stroke. Realising that Whitey is in trouble, the police ring for an ambulance and Whitey is taken to hospital in a comatose state. All his wife, Jessalyn, and their five adult children, Thom, Beverly, Lorene, Virgil and Sophia, know, is that the police gave Whitey aid. Their report on the incident with Dr Murthy does not mention John Earle McClaren. It will only be later when Thom becomes suspicious of some of his father’s injuries – Whitey supposedly crashed his car but there is no sign of an accident – and when Dr Murthy manages to track down Thom to tell him what really happened, that Thom will undertake to either have the police officers involved criminally charged, or bring a civil suit against them.

With this opening my expectations were immediately shaped by my reading of A Book of American Martyrs. That book opens with the killing of Dr Gus Vorhees, who works in an abortion clinic, by Luther Dunphy, a conservative Christian. The horrendous scene establishes the rest of the narrative, following the lives of Vorhees and Dunphy’s families, along with issues surrounding abortion. The support of evangelicals for Trump and their long-term hope that Roe v Wade, the landmark case that legalised abortion in America, might be overturned by a conservative Supreme court, explains a lot about divisions in American politics, and the current push to confirm Amy Coney Barrett before Trump is potentially removed from office. That’s the kind of political backdrop for that book and it’s is easy to assume that Oates’ dramatization of the abortion issue in A Book of American Martyrs will be a template for a treatment of the Black Lives Matter movement in America and around the world this year, inflamed by the police killing of George Floyd.

But that’s not really the case and for that reason, it is possible to be somewhat disappointed in Night. Sleep. Death. The Stars. But readers more familiar with Oates’ work than me suggest this book is better compared to We Were the Mulvaneys. A brief synopsis of that book tells the story of a young girl raped at a party, her estrangement from her father as a result of her failing to report the rape, and the long process of healing for the family. Night. Sleep. Death. The Stars. is more like that. Rather than making the main focus of the story about systemic racism, focussing on the effects of the opening violent incident not only upon Whitey’s family, Murthy’s family and possibly even the perpetrators, as she did in A Book of American Martyrs, Oates’ chooses to write a gentler tale about the effects on Whitey’s family of his loss, of how relationships define us, as well as meditate upon the humbling place of our lives within the universe.

There is a sense in the story that we are social beings. That our relationships are akin to environmental factors working upon the organisms of nature. If we adapt to our changing circumstance, we are fit for survival. But if we do not, death is an ever-present possibility: When you realize; as the life goes out in another, it is your own life that shrivels and expires.

This is ably demonstrated by the effect Whitey’s death has upon his family, particularly his wife, Jessalyn. Whitey is an old-style patriarch. He’s been mayor of Hammond, but that was 20 years ago and it’s clear many in the community have forgotten this fact. Certainly, the police officers who assaulted him did not recognise him. But for his family, Whitey has been the lynch pin in their lives. Without Whitey, Jessalyn loses purpose. As a widow she has no one to guide her and no one to serve. She wonders why she continues to live and contemplates suicide. For Thom and Beverly, Whitey’s death highlights troubles in their own marriages. And Thom is put under new pressures: left in charge of the family business, he feels the need to assume his father’s role in the family, but cannot convince his mother or sister, Beverly, that his father should receive an autopsy. Virgil, the black sheep of the family, is an artist living in a commune. He receives an equal share of his father’s bequest with his siblings, which causes much chagrin. His new-found wealth will change Virgil in subtle ways and cause him to question his own values. Sophia, a lab assistant hoping to complete a PhD, becomes involved in a relationship with Alistair, her boss, somewhat older than her. But her absence from the lab during Whitey’s time in hospital causes her to re-evaluate the ethics of her work, which involves experiments on animals. And Lorene, a school principal, perhaps one of the most interesting and appalling characters in this book, feels her life become unhinged. Doubting her parents’ love, she leads a life of paranoia, full of fear that her reputation will be trashed on social media by her students. Fearful of her students and mistrusting of her colleagues, her life is spinning out of control as she embraces her impulse for revenge.

It’s possible to be critical of the book; that it essentially avoids the issues of racism which is the catalyst for the story, and that it is, instead, the story of wealthy, privileged white Americans. That last part is true, at least, but the book doesn’t entirely avoid the race issue. Dr Murthy makes further brief appearances in which it is clear he understands race was a major factor in his targeting by police. When Jessalyn learns the truth about her husband’s death, that his stroke was precipitated by an assault, she attends a meeting – open to ‘All Citizens Concerned with Hammond Police Department Racism, Brutality & Injustice’

– where her presence is regarded with much suspicion. The group is comprised entirely of black people. The point is obvious. It is black people who are targeted by police. Jessalyn’s presence is regarded a self-serving. And Thom’s efforts to gain some justice for his father show how difficult it is, even for a wealthy white man, to do anything against systemic violence.

But the book doesn’t just focus on systemic racism or police brutality. Oates’ theme is larger here. When Jessalyn begins a new relationship with Hugo Ramirez, the family reacts negatively. Leo Colwin is considered a more suitable second husband for Jessalyn. He is white, has his own wealth and property but he is also boring. Hugo, being Puerto Rican, is assumed to be a grifter, manipulating Jessalyn for her wealth (they’re after her money – I mean he’s after her money!

). And Thom and Lorene show that violence is not exclusive to the police, either. Thom threatens a homeless man his mother tries to help, and is willing to beat an old stray cat to death because he believes its presence is bad for his mother. Lorene, who encourages him to do it, is willing to destroy the futures of her brightest students if she perceives they are critical of her.

It would be too harsh and inaccurate to criticise the book for being interested only in white privilege. At the heart of the novel is the issue of grief and loss. Jessalyn has lost her husband of almost fifty years, her adult children miss their father, and it is clear that Hugo harbours deep grief for his deceased son and others who have passed from his life. Whitey’s death is a signal that life is impermanent; that any situation in our lives is only temporary. Losing someone close is also a reminder of our own mortality. Each of the characters face their mortality, even thoughts of self-destruction, in the wake of Whitey’s death.

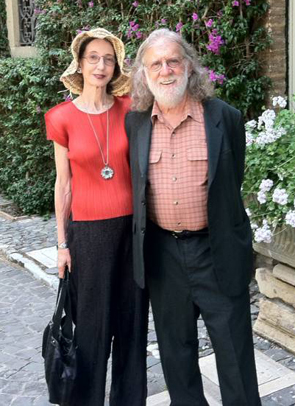

It’s tempting, also, to read the novel biographically. Oates’ own husband, Charlie Gross, to whom the novel is dedicated, died April 2019, and it’s tantalising to wonder whether his death changed the story. Gross was a scientist teaching at the same university as Oates when they were first introduced. His work with animals to map how sensory cells work and his extensive travels around the world to conduct his research seem to be represented to a limited extent by Hugo (an artist, granted, but a photographer who documents the world) who introduces Jessalyn to an exciting new life of greater independence, and a new way to understand her place in the universe during their trip to the Galapagos Islands.

Whether readers connect with the book or not will ultimately depend on their attitudes to death, including their spiritual beliefs. This is not a Christian story. While Whitey may remain a presence in his family’s life – characters often seem to converse with Whitey, even seek his advice – his perceived presence is more the result of the impact he has had on his family’s lives, resulting in an internal conversation with a memory of Whitey, rather than a literal spiritual presence. Besides, the trip to the Galapagos should be a clue – Darwin based many of his observations about evolution on his study of the creatures of Galapagos – along with Oates’ reference to Walt Whitman’s poem, ‘A Clear Midnight’ in her title. Night. Sleep. Death. The Stars. Is a meditation upon the self and the impact others have upon our lives. The book may look toward death, but it does so in the spirit that there is much to be lived of our lives before death, itself: that in gazing upon death and understanding our place in the universe, we gain the courage, as Jessalyn does, to more fully live our lives.

How we sift through ourselves, with others. Clasping at hands that turn transparent, that dissolve in our touch. Crying out No! Wait! Don’t leave me, I can’t live without you - and in the next instant they are gone, and we remain, alive.

Night. Sleep. Death. The Stars. doesn’t pack the same dramatic punch as A Book of American Martyrs, nor does it as fully engage in the current issues with which it is concerned. This is a more philosophical book, asking us to consider our place within our social and familial lives, and within the wider world. It encourages us to consider how we live our lives and how they might be enlivened through our relationships. It is a meditation on death and what meaning we may draw from its presence in our lives. Some will be moved by this book, others may be disappointed. Nevertheless, I thought it was thought-provoking with a rich narrative.

A CLEAR MIDNIGHT.

- THIS is thy hour O Soul, thy free flight into the wordless,

- Away from books, away from art, the day erased, the lesson done,

- Thee fully forth emerging, silent, gazing, pondering the themes

- thou lovest best,

- Night, sleep, death and the stars.