God’s Ephemera

The Death Trilogy #2

Mark Bryce

This story originally appeared in EarRat Magazine, Volume 6, September 10th 2022. The theme for this issue was ‘Ephemera’. You can view the original magazine by clicking here.

In this story the narrator contemplates memory, identity and death – a death!

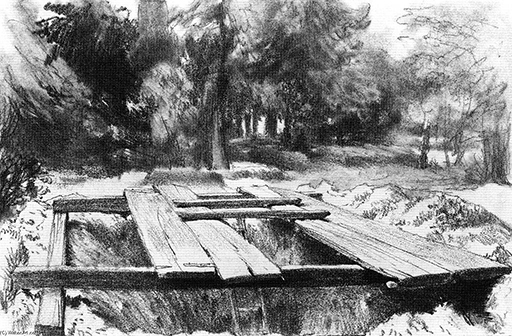

If you walk through a cemetery and see an open grave, ready to receive a body, you know that you have an opportunity to commit murder and get away with it.

I think this as we pass through our local cemetery, not far from our house. Thoughts like this routinely cross my mind. Not all are so dark, but they come to me, unbidden, like light and shadow under the trees. My wife and I walk this route every weekend to avoid a blind corner on the road where there is no pedestrian path and cars are upon you before you know it. The cemetery has a gravelled road that cuts through its centre, forming a broad turning circle at one end where we enter through the bush, and reconnecting with the road on the other side, which is our walking route into town.

“You know the difference between a cemetery and a graveyard?” my wife asks. A graveyard is attached to a church, I think.

“A graveyard is a part of the grounds of a church,” my wife tells me. I nod, waiting for the rest. “Cemeteries were probably first used as populations increased, making space difficult to find in small graveyards. Can you imagine in times of plague?”

These small sallies against the bulwark of existence; small sorties to fend away nothingness encroaching between us.

I think of those first people buried outside the church precinct, long ago, and wonder what their families may have thought about that. And then I think of Rookwood, a cemetery closer to Sydney, although Rookwood is probably more correctly described as a Necropolis. It’s the largest cemetery in the Southern Hemisphere. Back in the nineteenth century, when travelling wasn’t as easy as now, families would make a day out of visiting the graves of loved ones, with picnic lunches and games for their children to play. I buried my father there and my mother too, the final locus of my fading memories.

I note that the new section in our local cemetery, cleared from the bush only a few years ago, is rapidly filling, and I decide that it won’t be too many more years before the cemetery will be full. It is the same at our local tip, only a few suburbs away. It is sited in a small valley and years of community refuse have created a mountain you can now drive your car onto. In the past few years the council installed unloading bays at the base of the mountain where you can back your car up and toss your rubbish into a large bin below if you want to avoid the trek to the top of the pile. Eventually, the bins are full and a truck with hydraulics lifts them into the air and trundles them up the mountain. The council cleared more bush a couple of years ago to extend the tip on the other side of the valley, but I imagine it would be like the cemetery, the detritus of life spreading out and rising.

Everything is filling up. Except memories. Memories do not fill up like this.

Memory is a slow-leaking sieve in which all that is likely to remain when the details of life have escaped is the ephemera of existence. In my garage I have parts of my father. There is a magnifying glass he took out one day during summer to show me how to concentrate the sun's rays to burn grass; a pair of pliers with red insulation handles he used to cut wire with; a lawnmower he hit with a hammer because it wouldn't start and then had to have repaired; a large glass jar with clips and a rubber seal he used to preserve a snake he killed in the long grass down the back yard. These things, hard and tangible, fill my mind endlessly like a museum of the past. But they lack context. He is not there. In his wake are only the words that get repeated and these fingerprints of his passing. Things. Things. A hand-saw, toolbox, axe. They crash and clatter and impose themselves. But my father is gone.

My mother, likewise exists now only in bibs and bobs that litter the house with hopeful reminiscence: her crocheted rugs which I gave to the dog, or that table she’d rescued and refurbished as her personal project. She had imagined it at our doorway, the first thing guests would see – where they’d put their keys or stop to inspect framed photos that made us look like them. Photos before photos became digital, their colours fading, inscriptions printed on their backs increasingly obscure to me.

I remember the table filled my mother with pride.

My father had been obsessed with tracing our family history, but the pages upon which he recorded all that he discovered became desiccated leaves, their veins brittle, with nothing but names and dates and uncertain stories that became the questionable avatars of the lives of others. People reduced to things, I thought, and I burned the papers in the fire and watched generations dance into the sky.

I came to understand this vanity early on. The belief that lives could be reconstituted from the bones of existence.

I’d been put to bed one night. The light was turned off. I lay, staring at my ceiling, only a child, perhaps three or four or five, looking into the darkness that is non-existence, the sense of nothing above me, as though I could reach out and touch the lid of my coffin, touch the ceiling of my grave. I realised for the first time that I was not forever. And I cried. And because my parents could not hear me, I cried louder, and they came to me. And I said that I would die and they said not for a long time and they thought this would comfort me. Each person is a bright star, my mother told me, shining brighter and brighter as they grow. And the special stars – and by her telling me this I thought she spoke of me – do special things that make them shine brightest of all, like a comet bursting in the sky for all to see, and they are remembered forever.

Even so, each night I was settled into my grave I could not explain to them why I had trouble closing my eyes: why I found it difficult to sleep. My mother’s reassurance was a veil of expectation that now shrouded my life, like a burden I had not expected to bear.

My wife, who works in childcare, is full of happiness and she tells me of the happy moments she spends with other people’s children during her days. As the years have passed we have become so very different that people wonder at us with a polite laugh that is meant, I think, to hide perplexity.

She says, as we walk, “That is so and so’s grave”, which I know – I think I told her the first time – but she is like a hopeful child, scraping at the bottom of an empty biscuit jar. “He wrote that thing.”

I woke up one morning – this is years after I cried because I knew I would die – and realised that every moment I existed, everything I said and did which defined me, was being swept away with the tide of every moment. I wondered at famous people, if they knew before they died how lucky they were, that something of them would be remembered. Which gave me an idea. I could make a record my life, moment by moment, and then nothing would be lost. Like the boy holding back the waters with his finger in the dyke – stories I’d heard at school – Canute ordering back the waves. So I grabbed an exercise book that I had spare from my table and a pen, and I waited. Waited for something to happen. But neither my mother nor my father were yet awake, and I knew that until they were, nothing could happen and time could not shunt its train onto the morning’s main line. So I made a noise, or maybe I said something – memory! – and my mother awoke and said What’s that?

And I wrote, ‘“What’s that?” said mother.’

And I said that it was just something (I can hardly tell you what now) and I wrote that down too, and continued to write everything she said and everything I said until my mother was out of bed and my father was stirring and the futility of my project – the hope that existence might be stolen back from death by recording its minutiae – became apparent in my mother’s quizzical expression. I abandoned my project that morning and the horror of existence became plain to me. This pen. This book. This toy I found in the cereal packet. A waterproof watch I was wearing years later as I almost drowned. Its tick tick ticking like a heart that would outlive my own.

Objects. Things. The trivialities of my existence might be lost or stolen, passed on or thrown away. But they were what they were, and as long as they existed, they might again be what they had been made. We – I mean the factories, and the governments that said they could conduct their business wherever it was that they made these things, and all the people who bought what they made and every act of possessing and brandishing and displaying and coveting – had made the adornments of our lives our testament to the future.

I, on the other hand, had been made to be unmade. I was God’s ephemera.

Like a faint star burning away.

I call over to my wife as we return from our walk later in the afternoon. The morning has been bright blue and the air has been warm. But the clouds now roll across the sky like a frown. I wait for my wife to catch up. She is distracted by something, a flower perhaps, and she has stopped to look. Meanwhile, I look into the open grave again and wonder whether the change in the weather will bring rain. The funeral is probably tomorrow and the ground here will turn to a thick slurry. Eulogies will be spoken: kind words. Because moments of quotidian sadness, bad behaviour and shit-faced drunkenness will already be forgotten, and there will be one or two stories to be shared, ones everyone knows and find comforting, at least as much as they can muster between them, and then the mourners will leave in a hurry and soon there will be no-one to remember. The ground is probably soft, I think. The cemetery workers use a small earth mover to dig, but I am willing to bet it would not be much harder to move the earth with a shovel.

I recall something, now, the way memories intrude sometimes like light through the trees. We went on a holiday in Tasmania several years ago and toured the ruins of the convict settlement at Port Arthur. Port Arthur had been the scene of a gun massacre in 1996, which helped usher in tougher gun laws in Australia. Just off shore there is a small island called Isle of the Dead. It is called that because convicts who died in the prison colony were buried there. But the island is small, so prisoners had to be buried one on top of another, sometimes six high to a grave.

But it is the massacre everyone remembers these days.

“What did you want?” my wife asks as she sidles up to me. She is holding a splay of flowers picked from beneath a tree.

I nod at the grave. “How deep do you think they dig them?” I ask.

My wife looks into the grave for a moment and considers.

“The saying is they put you six feet under,” she recalls. She likes facts. They are reassuring.

“I know that,” I say, ruminating. “But it’s really hard to tell, don’t you think? I wonder how deep this one is.”

But she isn’t interested in the grave. “I picked these flowers,” she says, thrusting them forward enthusiastically.

“They’ll be just perfect,” I say. I take them from her and I press my hand against her back as we look into the grave. For moments we stand, until I feel the muscles in her back go tense and she tries to push back, trembling like a small dance that nobody sees.

© Mark Bryce, 2024