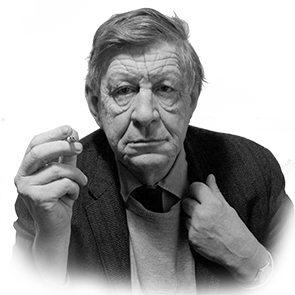

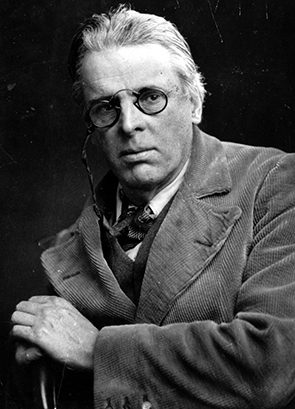

At the age of 53, Wystan Hugh Auden is widely considered one of the greatest poets in English of this century, along with Yeats and Eliot. His work is profound, varied, and prolific, and as I discovered, his conversation reaches similar heights.

The following interview took place over the telephone, after I was unexpectedly prevented from visiting Oxford, where Auden is professor of poetry. It is not an arduous post, requiring the delivery of three lectures a year (his are very popular) and leaving plenty of time for reflection. Auden began by saying that he had been thinking about the position of a poet invited to give lectures or criticism.

“The critical opinions of a writer should always be taken with a grain of salt,” he said, speaking with a heavy smoker’s rasp. “For the most part, they are manifestations of his debate with himself as to what he should do next and what he should avoid.”

“So why bother to publish such private thoughts?"

“It is a sad fact about our culture that a poet can earn much more money writing or talking about his art than he can by practicing it.”

Chuckle, cough.

“What about full-time critics,” I wondered, “is their approach more objective?”

Auden told me good literary critics are rarer than good poets or novelists. When I asked why, he suggested, “One reason is the nature of human egoism. A poet or a novelist has to learn to be humble in the face of his subject matter which is life in general. But the subject matter of a critic, before which he has to learn to be humble, is made up of authors, that is to say, of human individuals, and this kind of humility is much more difficult to acquire. It is far easier to say—‘Life is more important than anything I can say about it’—than to say—‘Mr A’s work is more important than anything I can say about it.’”

“When did you begin writing poetry?”

“One Sunday afternoon in March 1922.”

He was then about 15.

“Were you inspired by poetry you had read?”

[Read More]

[Read More]

[Read More]

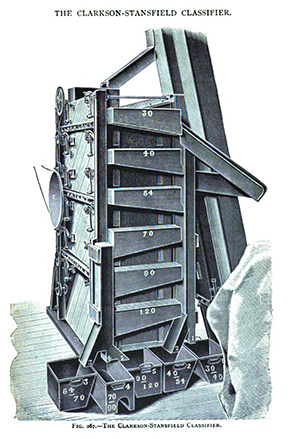

“I scarcely knew any poems and I took little interest in what is called Imaginative Literature. Most of my reading had been related to a private world of Sacred Objects. Aside from a few stories like George Macdonald’s The Princess and the Goblin, Jules Verne’s The Child of the Cavern, the subjects of which touched on my obsessions, my favourite books bore such titles as Underground Life, Machinery for Metalliferous Mines, Lead and Zinc Ores of Northumberland and Alston Moor, and my conscious purpose in reading them had been to gain information about my sacred objects. Between the ages of seven and twelve my fantasy life was centered around lead mines.”

Auden speaks in perfectly formed sentences, and even paragraphs. I’d become so preoccupied in taking notes that I hadn’t interrupted for a while, but the lead mines demanded notice.

“What?” I barked.

Another chuckle. “I spent many hours imagining in the minutest detail the Platonic Idea of all lead mines. In planning its concentrating mill, I ran into difficulty: I had to choose between two types of a certain machine for separating the slimes. One I found more ‘beautiful’ but the other was, I knew from my reading, the more efficient. My feeling at the time, I remember very clearly, was that I was confronted by a moral choice and that it was my duty to choose the second.”

Auden was born in York in 1907, and published his first book of poems (called Poems) at the tender age of 23. He was an almost instant success and quickly gained a reputation as a declamatory left-wing writer. Preaching ran in his family – while his father was a doctor and mother a nurse, both his grandfathers had been vicars.

“How did you learn to write poetry?” I asked. “Did you have a mentor?"

“A would-be poet serves his apprenticeship in a library. This has its advantages. Though the Master is deaf and dumb and gives neither instruction nor criticism, the apprentice can choose any Master he likes, living or dead, the Master is available at any hour of the day or night, lessons are all for free, and his passionate admiration of his Master will ensure that he work hard to please him. To please means to imitate and it is impossible to do a recognisable imitation of a poet without attending to every detail of his diction, rhythms and habits of sensibility.”

“And —”

“Later in life, incidentally, he will realise how important is the art of imitation, for he will not infrequently be called upon to imitate himself.”

One of the irritatingly wide range of talents Auden is blessed with is humour, deployed so effectively it often obscures his firm views.

“What does a poet need before he can break away from his masters?” I asked.

“He will never know what he himself can write until he has a general sense of what needs to be written. And this is the one thing his elders cannot teach him, just because they are his elders; he can only learn it from his fellow apprentices with whom he shares one thing in common, youth. The discovery is not wholly pleasant. If the young speak of the past as a burden it is a joy to throw off, behind their words may often lie a resentment and fright at realising that the past will not carry them on its back.”

“What should a young poet study at university?” I asked.

“There is nothing a would-be poet knows he has to know. He is at the mercy of the immediate moment because he has no concrete reason for not yielding to its demands and, for all he knows now, surrendering to his immediate desire may turn out later to have been the best thing he could have done. It is hardly surprising, then, if a young poet seldom does well in his examinations.”

Auden studied at Christ Church at Oxford, changing from biology to English and obtaining a third-class degree.

I ventured the opinion that more and more young people these days want to become writers, and he agreed. “In our age,” he said, after another brief coughing fit, “if a young person is untalented, the odds are in favour of his imagining he wants to write. In our society, the process of fabrication has been so rationalised in the interests of speed, economy and quantity that the part played by the individual factory employee has become too small for it to be meaningful to him as work, and practically all workers have become reduced to labourers. It is only natural, therefore, that the arts, which cannot be rationalised in this way, should fascinate those who, because they have no marked talent, are afraid, with good reason, that all they have to look forward to is a lifetime of meaningless labour.”

“But they must like literature, surely?”

“This fascination is not due to the nature of art itself, but to the way in which an artist works; he, and in our age, almost nobody else, is his own master. The idea of being one’s own master appeals to most human beings, and this is apt to lead to the fantastic hope that the capacity for artistic creation is universal, something nearly all human beings, by virtue, not of some special talent, but of their humanity, could do if they tried.”

“Are poets nice people?”

“Every ‘original’ genius, be he an artist or a scientist, has something a bit shady about him, like a gambler or a medium.” (Pause) “Only a minor talent can be a perfect gentleman; a major talent is always more than a bit of a cad.”

“Is the twentieth century conducive to being an artist?”

“In the purely gratuitous arts, poetry, painting, music, our century has no need, I believe, to be ashamed of its achievements, and in its fabrication of purely utile and functional articles like airplanes, dams, surgical instruments, it surpasses any previous age. But whenever it attempts to combine the gratuitous with the utile, to fabricate something which shall be both functional and beautiful, it fails utterly. No previous age has created anything so hideous as the average modern automobile, lampshade or building.”

Auden moved to America in 1939, partly, he said, to escape his reputation as a left-wing poet. By then his views were becoming more nuanced, and he was soon to become a Christian. I asked him if it was a good thing for poets to be politically engaged. No doubt drawing on his own past, he said, “The cause, I fear, is less their social conscience than their vanity; they are nostalgic for a past when poets had a public status.”

“Why can’t they produce useful insights nonetheless?”

“Poets are, by the nature of their interests and the nature of artistic fabrication, singularly ill-equipped to understand politics or economics. Their natural interest is in singular individuals and personal relations, while politics and economics are concerned with large numbers of people.” He stopped, and I was about to ask another question when he went on: “The poet cannot understand the function of money in modern society because for him there is no relation between subjective value and market value; he may be paid ten pounds for a poem which he believes is very good and took him months to write, and a hundred pounds for a piece of journalism which costs him but a day’s work. If he is a successful poet he is a member of the Manchester school and believes in absolute laisser-faire; if he is unsuccessful and embittered, he is liable to combine aggressive fantasies about the annihilation of the present social order with impractical daydreams of Utopia. Society has always to beware of the utopias being planned by artists manques over cafeteria tables late at night.”

“Modern poetry seems to have alienated much of poetry’s traditional audience, hasn’t it?”

“There is a certain kind of person who is so dominated by the desire to be loved for himself alone that he has constantly to test those around him by tiresome behaviour; what he says and does must be admired, not because it is intrinsically admirable, but because it is his remark, his act. Does not this explain a good deal of avant-garde art?”

“You have never produced an autobiography. Do you approve of the genre?”

“Biographies of writers, whether written by others or themselves, are always superfluous and usually in bad taste.”

“Could you explain?”

“An honest self-portrait is extremely rare because a man who has reached the degree of self-consciousness presupposed by the desire to paint his own portrait has almost always also developed an ego-consciousness which paints himself painting himself, and introduces artificial highlights and dramatic shadows.” After another cough, he added: “No man, however tough he appears to his friends, can help portraying himself in his autobiography as a sensitive plant.”

“Do you think about yourself very much?”

[Read More]

[Read More]

[Read More]

“The same rules apply to self-examination as apply to confession to a priest: be brief, be blunt, be gone,” he replied, and then quoted with approval Cesare Pavese’s opinion: “‘One ceases to be a child when one realises that telling one’s trouble does not make it any better.’”

I am not sure of the therapeutic value of this advice, but it might have professional utility. Possibly Auden, like many artists, has an instinctive awareness that if he understood himself too well, he would no longer need to produce art.

Moving on, I said, “You’ve said you find detective stories an addiction. Why must there be a murder, why won’t any other crime do, no matter how awful?”

“Murder is unique in that it abolishes the party it injures, so that society has to take the place of the victim and on his behalf demand restitution. It is the one crime in which society has a direct interest,” Auden explained, and went on to suggest that the murder should occur in a peaceful society, some Great Good Place, (for contrast) and a closed one (to limit the number of suspects.)

“Chandler is different, isn't he?”

“I think Mr Chandler is interested in writing, not detective stories, but serious studies of a criminal milieu, the Great Wrong Place, and his powerful but extremely depressing books should be read and judged, not as escape literature, but as works of art.”

[Read More]

[Read More]

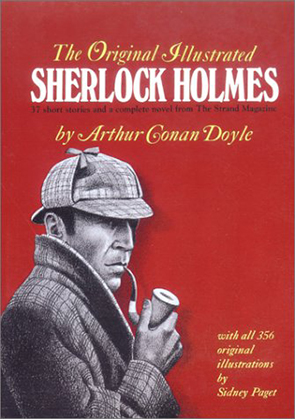

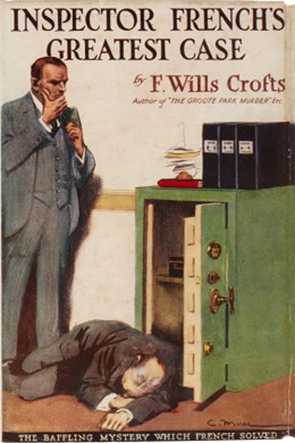

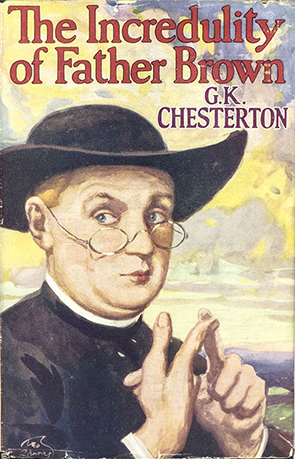

“Which authors of the classical stories do you admire?”

“The job of the detective is to restore the state of grace in which the aesthetic and the ethical are as one. Since the murderer who caused their disjunction is the aesthetically defiant individual, his opponent, the detective, must be either the official representative of the ethical or the exceptional individual who is himself in a state of grace. Completely satisfactory detectives are extremely rare. Indeed, I only know of three: Sherlock Holmes (Conan Doyle), Inspector French (Freeman Wills Croft), and Father Brown (Chesterton). The amateur detective genius may have weaknesses to give him aesthetic interest, but they must not be of a kind which outrage ethics. The most satisfactory weaknesses are the solitary oral vices of eating and drinking or childish boasting. In his sexual life, the detective must be either celibate or happily married.”

Holmes, Auden said, is “in a state of grace because he is a genius in whom scientific curiosity is raised to the status of a heroic passion. He pays the price for his scientific detachment by being the victim of melancholia which attacks him whenever he is unoccupied with a case (eg, his violin playing and cocaine taking).”

And Father Brown?

“He solves his cases, not by approaching them objectively like a scientist or a policeman, but by subjectively imagining himself to be the murderer.”

I wondered what sort of person reads detective novels, and Auden said, “Like myself, a person who suffers from a sense of sin. The magic formula is an innocence which is discovered to contain guilt; then a suspicion of being the guilty one; and finally a real innocence from which the guilty other has been expelled. The fantasy, then, which the detective story addict indulges is the fantasy of being restored to the Garden of Eden.”

“You’ve spent some years in the United States. Do you find Americans very different from Europeans?”

“Our different pasts have not yet been completely erased. The most striking difference between an American and a European is the difference in their attitudes towards money. Every European knows, as a matter of historical fact, that, in Europe, wealth could only be acquired at the expense of other human beings, either by conquering them or by exploiting their labour in factories. In the United States, wealth was also acquired by stealing, but the real exploited victim was not a human being but poor Mother Earth and her creatures who were ruthlessly plundered.”

“The Indians—”

“It is true that the Indians were expropriated or exterminated, but this was not, as it had always been in Europe, a matter of the conqueror seizing the wealth of the conquered, for the Indian had never realised the potential riches of his country. Thanks to the natural resources of the country, every American, until quite recently, could reasonably look forward to making more money than his father. What an American values, therefore, is not the possession of money as such, but his power to make it as proof of his manhood; once he has proved himself by making it, it has served its function and can be lost or given away. In no society in history have rich men given away so large a part of their fortunes.”

I hadn’t asked Auden enough about love. His personal relationships are largely unknown (he is homosexual), but his poetic reflections seem to indicate an almost romantic hunger for permanent relationships.

“Do you believe in love?” I asked.

“No notion of our Western culture has been responsible for more human misery and more bad poetry than the supposition that a certain mystical experience called falling or being ‘in love’ is one which every normal man and woman can expect to have. The experience certainly does occur, but only, I should guess, to those with a livelier imagination than the average. Under its influence the poet should write better poetry—about something else.”

“Do you believe in marriage?” I asked.

“Like everything which is not the involuntary result of fleeting emotion but the creation of time and will, any marriage, happy or unhappy, is infinitely more interesting and significant than any romance, however passionate.”

After this original response – I was trying to recall if I’d ever read a novel about a happy marriage – the phone went dead, and my attempts to ring back were unsuccessful. Auden had given me a wonderful interview. Perhaps, like a completed poem, he now regarded the matter as finished. He is, apart from everything else, a great one for moving on.

[Read More]

Comments

No one has commented yet. Be the first!