[Read More]

I first met Stendhal in Paris in 1824, at the home of Dr William Edwards. He was a short, plump man, wearing a rather good toupee. This, with his brown hair and whiskers, framed a face in which the dominant features were a pair of incredibly lively eyes and a small but confident mouth. Even when his lips were closed, which was rarely, they looked about to open with some bon mot or slightly baffling declaration.

He told me his non-literary name was Marie-Henri Beyle, and I asked his profession. “I am simply an observer of the human heart,” he replied with dignity. On learning that I had just come to Paris he advised: “When I arrive in a new town, I always ask who are the twelve prettiest women, who are the twelve richest men, and which man can have me hanged?”

Stendhal was a supporter of Napoleon. Since the emperor’s exile in 1815, most of the bright young men who were educated and employed by him have lost their jobs and turned in desperation to literature. Stendhal affects to despise the new regime, referring to it as ‘the party of candle-snuffers’, in reference to its anti-revolutionary principles. Yet free speech flourishes as never before. Stendhal benefits from this state of affairs even as he condemns it — a position taken not infrequently by writers.

Stendhal holds the attention of an audience partly with his wit and partly with the sense of unease he creates. His meaning jumps around so quickly that one must either ignore him or give him one’s full attention, and most people do the latter. There is little consistency: in a short space of time he will come at a subject from several different angles. His recent book on love (more on this soon) is probably the strangest work of genius ever written. In the weeks following our first meeting, I pieced together the story of its author.

Henri Beyle was born in Grenoble in 1783. His mother died when he was seven, and Henri, who was educated at home until he was 13, led a lonely childhood existence enlivened by literature. His attitude to women was shaped on one side by romantic fiction such as Rousseau’s La Nouvelle Heloise, which Henri claims to have memorised, and on the other by what he called “books to be read with one hand only”, which he borrowed clandestinely from his grandfather’s library. In adolescence he enjoyed Les Liaisons Dangereuses, Don Quixote and Shakespeare.

There followed 14 years with the armies of Napoleon. He does not seem to have taken part in any fighting, serving on the supply side of things, but he was involved in the disastrous retreat from Moscow. He had fallen in love with Italy while serving there — it was at Novara, a small town west of Milan, that he had seen his first opera at the age of 17, and become a devotee for life. After 1815 he spent six years there.

[Read More]

Two Great Novels by Stendhal

[Read More]

You can also read our review of The Red and the Black by clicking here

In 1814 he published his first book, Lives of Haydn, Mozart, and Metastasio, almost all of its material stolen from other writers, and in 1817 published his history of Italian painting. Both books were printed at their author’s expense and sold poorly. Then came a more successful book, Rome, Naples, and Florence, and finally, in 1822, after the manuscript had been lost in the post for a year, De l’Amour. It is basically a long essay on the experience of falling in love.

De l’Amour was inspired by an affair which occurred over almost three years in Milan or, more precisely, occurred in Stendhal’s mind when he was in Milan, for the object of his passion remained impervious. It also drew on his many more successful amorous adventures, which had taken place over many years in a number of countries. In the book he is by turn clown and wise observer.

After witnessing Stendhal in action on that first evening I talked to Dr Edwards about him, and was advised to read the book on love. My French being poor, it occurred to me to ask its author to explain his thoughts to me, and a few days later we had a very interesting conversation in a restaurant near his lodgings.

Stendhal speaks a fluent but individual version of English, and in what follows I have ironed out his more distracting bumps of grammar and vocabulary.

“Paris, thanks to the superiority of its conversation and literature, is and always will be the drawing-room of Europe,” he announced at the start of our conversation.

But is it the best place for love?

“A Frenchman thinks he is the unhappiest man in the world, and verging on the most ridiculous, if he has to spend his time alone. But what is love without solitude?”

“Well, what is love with solitude?” I asked.

Stendhal smiled, leaned back in his chair, and admired his small hands for a moment. I asked him to start from the beginning, and to explain to me his theory of falling in love.

“Here is what happens in the soul,” he said patiently, as though reciting a much-loved verse from memory. “One: admiration. Two: you think how delightful it would be to kiss her, to be kissed by her, and so on . . .”

“Yes?”

“Three: hope. You observe her perfections, and it is at this moment that a woman really ought to surrender, for the utmost physical pleasure.”

“And if not?”

“Four: love is born. Five: the crystallization begins.”

“Crys–”

Stendhal grew animated. “It is a pleasure to endow her with a thousand perfections and to count your blessings with infinite satisfaction. In the end you overrate wildly, and regard her as something fallen from heaven.”

”I’m not sure I understand.”

[Read More]

Two Great Novels by Stendhal

[Read More]

[Read More]

Stendhal just nodded. “Excessive familiarity can destroy [crystallization]. Leave a lover with his thoughts for 24 hours, and this is what will happen. At the salt mines of Salzburg, they throw a leafless wintry bough into one of the abandoned workings. Two or three months later they haul it out covered with a shining deposit of crystals. The smallest twig, no bigger than a tom-tit’s claw, is studded with a galaxy of scintillating diamonds. The original branch is no longer recognisable. What I call crystallization is a mental process which draws from everything that happens new proofs of the perfection of the loved one.”

“I see why solitude is so necessary.”

Stendhal nodded again. “A man in love sees every perfection in the object of his love, but his attention is still liable to wander after a time because one gets tired of anything uniform, even perfect happiness. This is what happens next to fix the attention: doubt creeps in. He is met with indifference, coldness, or even anger if he appears too confident. A woman may behave like this either because she is recovering from a moment of intoxication and obeying the dictates of modesty, which she may fear she has offended, or simply for the sake of prudence or coquetry. The lover tries to recoup by engaging in other pleasures but finds them inane.”

“You're assuming he is sure he is in love, which is not always the case, surely. How can one tell?”

“When all the pleasures and all the pains attributable to all the other passions and all the other needs of a man cease abruptly to affect him.”

“So. What happens next, when doubt sets in?”

Stendhal looked out the window, seemingly recalling some past experience. “Always a little doubt to set at rest,” he murmured. “That’s what keeps one craving, that’s what keeps happy love alive. Because the misgivings are always there, the pleasures never grow tedious.”

There was a silence, which I broke by asking what effect these doubts had on the lover’s behaviour. Stendhal shook his head and straightened himself, looking at me again.

“He is seized by the dread of a frightful calamity and now concentrates fully. Thus begins the second crystallization, which deposits diamond layers of proof that “she loves me”. When the two crystallization processes have taken place, and particularly the second, which is far the stronger, the original naked branch is no longer recognisable by indifferent eyes, because it now sparkles with perfections, or diamonds.”

I asked if the French were particularly adept at love. He has visited London, and proceeded to express pessimism about the chances of romance in our kingdom.

“The modesty of women in England is the pride of their husbands,” he said disdainfully. “But, however submissive a slave may be, her company soon grows burdensome. Hence the fact that the men find it necessary to get gloomily drunk every evening, instead of passing the time with their mistresses as in Italy. In England the rich, bored with their homes, and on the plea of necessary exercise, walk four or five leagues every day as though man were created and placed on earth for the purpose of trotting. In this way they use up their nervous fluid through the legs instead of through the heart.”

“What about Italy?”

“No one could be idler than the young Italians; movement, which might blunt their sensibility, they find tiresome. Now and again they will walk half a league reluctantly for their health’s sake; and as for the women, a Roman woman does not cover as much ground in a whole year as an English miss will do in a week.”

[Read More]

I found Stendhal baffling. Like the rest of us these days, he is a Romantic, as much so as the most famous writer in Europe, Sir Walter Scott. But at the same time he is a Rationalist, a paradox that perhaps explains the confusion he so often induces. When one reads Scott one is always aware, however reluctantly, that life is elsewhere. When one reads Stendhal one knows that life is here, between his sentences. What lies elsewhere is happiness: for a self-proclaimed seeker of pleasure, Stendhal seems to have found it rarely.

In France today Stendhal is considered the great defender of Romanticism, the scourge of Classicism. He attained this position following an event in 1822, when a group of French liberals broke up a performance of Macbeth in Paris. Stendhal used this outrage to publish Racine et Shakespeare, an article which became a book. It is a fierce attack on the French passion for neoclassical drama, epitomised by the works of Racine, in which the observance of literary rules is more important than the observance of life. Stendhal uttered what for the French were blasphemies, claiming that there could be many scene changes within one act, that great drama need not be in verse, that great plays could contain characters from all walks of life. The honoured members of the Academie Francaise were satisfyingly outraged, and Stendhal's reputation was made.

And yet, at the same time as he was fighting the Classicists, he was fighting the Romantic tendencies towards diffuseness of thought and verbosity of expression. “Any really useful idea will certainly be despised in France if it can be expressed only in very simple terms,” he told me bitterly.

[Read More]

Yet it would be wrong to deduce from this that Stendhal’s writing is a headlong rush to embrace life in all its variety (just as it would be wrong to conclude anything at all from any words of Stendhal). The title page of the second volume of his history of Italian art carries the English dedication: “To the happy few”, which might serve as the motto of this man, whose greatest work to date is a dissertation on a fantastic and fleeting branch of love. (It may also be a tongue-in-cheek reference to the size of his readership at that time.) As the pieces of conversation recorded above suggest, Stendhal believes that art and happiness are the preserves of those living in very specific places and circumstances—ideally, it seems, of those living in Milan and spending their time crystallizing while attending the opera or looking at paintings.

For Stendhal, the observer of the human heart who has no wife, no children and no close relatives at all, happiness lies in art and in nature. Other people, except as prompts for the imagination and objects of study, are relatively unimportant. When I congratulated him on the success of his latest book, a life of Rossini, he shrugged and looked out the window with apparently genuine distaste. No success, he said, could make up for “the mud in which I am buried. I imagine the heights which my soul inhabits, like delightful hills. Far from these hills, on the plain, are fetid marshes in which I am plunged.” Happiness is elsewhere. Then Stendhal jumped up and, examining his appearance in the mirror with evident signs of approval, suggested we go down to see Mme Pasta.

*

[Read More]

[Read More]

[Read More]

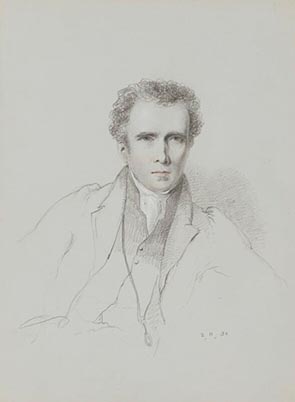

William Hazlitt arrived in Paris in early autumn. As one of the most hated—and most read—journalists in England, he needs no introduction for most readers, who will be familiar with his books and his essays, sketches and reviews published in the Examiner and other magazines. Of those publications that will not have him, the worst insult has come from the Quarterly Review, in which he has been described as a “slang-whanger” whose essays are written in “broken English” and leave behind them a trail of “slime and filth”.

All this because Hazlitt possesses a familiar style and is a radical. The man himself, strange to say, is most offended by the trivial jibe published in Blackwood’s, in which he was called “Pimpled Hazlitt”—a slur completely undeserved. For myself, I believe Keats got it right when he called Hazlitt “your only good damner, and if ever I’m damned—damn me if I shouldn’t like him to damn me.” Hazlitt is a good man. And, like many of his kind, he causes more trouble than most bad ones.

In appearance he is short and slight, with dark hair, pale skin, and pointed features. The journey to Paris occurred almost immediately after his recent marriage, which itself was on the heels of his divorce from his first wife. When he arrived, he looked terrible. “He has become so thin,” Mary Shelley noticed not long ago, “his hair so scattered, his cheekbones projecting. His smile like a sunbeam illuminating the most melancholy of ruins.” As soon as I heard he was in the city I hastened to his hotel, where I met his new wife, Isabella, a pleasant and stolid woman. His first wife, Sarah, had been selected for him by his friends, the Lambs, (a strange way of proceeding for a self-proclaimed revolutionary). She is an obsessive walker, and the marriage was a failure from the very start, when Charles Lamb could not stop himself laughing during the ceremony. Anyway, Isabella told me her husband had gone to the Louvre and I followed, thinking of what I knew about Hazlitt.

He was born in 1778, the son of a Dissenting minister, a fact whose importance cannot be underestimated. “It was my misfortune,” he has said, “to be bred among Dissenters who look with too jaundiced an eye at others, and set too high a value on their own peculiar pretensions. From being proscribed themselves, they learn to proscribe others.”

The French Revolution transformed the young Hazlitt just as it did Wordsworth, who has famously written “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive/But to be young was very heaven!” In 1798 a Dissenter and dissenter named Samuel Coleridge came to preach in a town near Hazlitt’s. The poet was intent on becoming a minister there, and the 20-years-old Hazlitt went to hear him, and was treated to an anti-war sermon. He was besotted.

Coleridge spent a night with Hazlitt’s father, and the next morning received a letter from a patron, offering him 150 pounds a year if he would devote his life to poetry and philosophy. Abandoning all thoughts of God’s ministry on the spot, he accepted the offer and went off to Somersetshire, asking Hazlitt to come visit in a few weeks. This the youth did, and met Wordsworth too. It was the year in which the two poets published their joint poetry collection Lyrical Ballads, that thunderclap of English Romanticism.

With subsequent events in France and Europe, Wordsworth and many others fell out of love with Napoleon. Even Coleridge lost his ardour, and coined the epithet ‘the Corsican’ to describe the emperor. Hazlitt never forgave the two poets their change of heart, and his recollections of their early acquaintance are perhaps coloured by this. His own reaction to the final defeat of Napoleon by the English and Prussians at Waterloo, as described by the painter Benjamin Haydon, was extraordinary: “He seemed prostrated in mind and body, he walked about unwashed, unshaved, hardly sober by day and always intoxicated by night, literally, without exaggeration, for weeks.” These days Hazlitt drinks no spirits and little of any other stimulant except green tea, of which he is extremely fond.

I missed him at the Louvre and finally met up with him at Dr Edwards’ salon. Stendhal was also there that evening, and Hazlitt was instantly won over. He was very impressed by meeting someone who had actually served under Napoleon, and soon Stendhal was reminiscing about his days with the emperor in Moscow. “We left the city, which was lit by the loveliest conflagration in the world, forming an immense pyramid that was like the prayers of the faithful, the base on earth and the apex in the heavens,” he enthused. “The moon appeared above the conflagration. It was a grand spectacle, but one would have had to have been alone to see it or surrounded by discerning people.” Stendhal sighed. “That is the sad circumstance which spoiled the Russian campaign for me, having done it with people who would have made the Colosseum or the Sea of Naples seem small.”

[Read More]

The two writers have a great deal in common, once one looks beyond the obvious fact of the fatness of one and the thinness of the other: same short height, same enthusiasms for Napoleon, painting, the theatre and Shakespeare. Stendhal greatly admired Hazlitt’s book, Characters of Shakespeare’s Plays, and had once written to him in praise of it. Both were great journalists and liberals, and spent some time discussing the virtues of the Edinburgh Review.

Later in the evening, Stendhal was entertaining a small group and I noticed Hazlitt sitting alone and looking tired. He asked me to help him home. It was a ten-minute walk to his hotel, but took us closer to half an hour, as we had to stop often. To take his mind off the pain I asked him about Coleridge, and this seemed to revive him: in hating he became healthy again.

“His mouth was gross,” Hazlitt said eagerly as he recalled their first meeting, more than 20 years ago, “his chin good-humoured and round, but his nose, the rudder of the face, was small, feeble, nothing—like what he has done.” He related how, when walking with Coleridge, “I observed that he continually crossed me on the way by shifting from one side of the footpath to the other. This struck me as an odd movement; but I did not at that time connect it with any instability of purpose or involuntary change of principle, as I have done since.”

I asked if the poets had read to him from the manuscript of Lyrical Ballads that summer, and he told me they had. “There is a [chaunt] in the recitation both of Coleridge and Wordsworth, which acts as a spell upon the hearer and disarms the judgement.” Hazlitt stopped walking in order to take a breath, and laughed harshly. “Perhaps they have deceived themselves by making habitual use of this ambiguous accompaniment.”

We moved on. “The present is an age of talkers, and not of doers,” he said, “and the reason is, we are growing old. We are so far advanced in the Arts and Sciences that we live in retrospect, and dote on past achievements. The accumulation of knowledge has been so great, that we are lost in wonder at the height it has reached, instead of attempting to climb or add to it; while the variety of objects distracts and dazzles the looker-on. We are like those who have been to see some noble monument of art, who are content to admire without thinking.”

I asked if he enjoyed any of Coleridge’s poems.

[Read More]

“The Ancient Mariner is the only one that we could with confidence put into any person’s hands, on whom we wished to impress a favourable idea of his extraordinary powers.”

”Why has he produced so little then?”

“He is a general lover of art and science, and wedded to no one in particular. It is hard to concentrate all our attention and efforts on one pursuit, except from ignorance of others.”

We were almost at the Hotel des Etrangers, which was as well, for Hazlitt was flagging badly, clutching his stomach.

“If Mr Coleridge had not been the most impressive talker of his age, he would probably have been the finest writer,” he said.

“He must have meant a lot to you when you first met?”

Hazlitt saw a passing bench and sat down on it abruptly, and said nothing for a moment, just gazing up at the new moon, which could be seen above the even roofs of the buildings around us.

After a while I saw that his face was still tilted at the moon, but his eyes were glazed and he was elsewhere. He began to speak, slowly. The thoughts were private but the feeling behind them was not halting but passionate. “I was at that time dumb, inarticulate, helpless, like a worm by the way-side, crushed, bleeding, lifeless,” he murmured, and paused before continuing, to breathe in the cold night air. He did not seem to be aware of my presence anymore. “My soul has remained in its original bondage; my heart, shut up in the prison house of this rude clay, has never found, nor will it ever find, a heart to speak to; but that my understanding also did not remain dumb and brutish, or at length found a language to express itself, I owe to Coleridge.”

Hazlittt stayed three months in Paris, but for much of that time was ill and remained in his rooms. I met his first wife, Sarah, in the street one day. She too was travelling, and had been to see him. Before striding off she told me he “gets his food cooked in the English way, which is a very great object for him”. I suspect travel was not easy for Hazlitt, and that he was one of those who journey more from dislike of the place they have left than any enthusiasm for where they are going.

Towards the end of his stay he wanted company, and I would go and sit with him in his rooms. He was, I discovered, producing a stupendous amount of journalism from his bed. At times he was depressed, and once greeted me with: “What abortions are these essays! What errors, what ill-pieced transitions, what crooked reasons, what lame conclusions! How little is made out, and that little how ill.”

“Not at all,” I cried, “they –”

“They are the best I can do,” he muttered, and there was a heavy silence. Then I told him that for many people he was the English Montaigne, and he seemed quickly pleased by the idea. “The great merit of Montaigne was, that he may be said to have been the first who had the courage to say as an author what he felt as a man,” Hazlitt said, gathering his strength again. “He was, in the truest sense, a man of original mind, that is, he had the power of looking at things for himself, or as they really were, instead of blindly trusting to, and fondly repeating what others told him they were. He has left little for his successors to achieve in the way of just and original speculation on human life.”

Hazlitt has elevated journalism at times almost to the heights of art, using a method most people would consider the opposite of artistic: simplicity. “I hate to see a load of bandboxes go along the street,” he said, “and I hate to see a parcel of big words without anything in them. It is not easy to write a familiar style. Many people mistake a familiar style for a vulgar style, and suppose that to write without affectation is to write at random. On the contrary, there is nothing that requires more precision.”

I asked about the differences between Wordsworth and Coleridge.

“Coleridge's manner is more full, animated and varied,” he said, “Wordsworth's more equable, sustained and internal. The one might be termed more [dramatic], the other more [lyrical]. Coleridge has told me that he himself liked to compose in walking over uneven ground, or breaking through the straggling branches of a copse-wood, whereas Wordsworth always wrote (if he could) walking up and down a straight gravel-walk, or in some spot where the continuity of his verse met with no collateral interruption.”

“Do you enjoy his poems?”

“They either make no impression on the mind at all, seem mere [nonsense-verses], or leave a mark behind them that never wears out. Wordsworth’s mind is obtuse, except as it is the organ and the receptacle of accumulated feelings; it is not analytic, but synthetic; it is reflecting, rather than theoretical.”

“Do you have any of Stendhal’s books?” I asked one day in his lodgings, examining the books on a shelf.

[Read More]

Hazlitt told me he had a copy of De l’Amour, that “charming little work” by “my friend Mr Beyle”. He seemed to stir uneasily, and rose to request some more tea. There was one book I knew of which was missing: his own Liber Amoris, about an unrequited love affair. Hazlitt sat down and began to talk on some subject, but I found myself thinking of the two books on love, and as I did so they began to mingle: I could not remember where the Frenchman’s work of theory ended and the Englishman’s record of experience began. This strange and unexpected confusion disturbed me and I could no longer think clearly. I had to stand up and leave suddenly, to Hazlitt’s surprise.

Liber Amoris is one of the most embarrassing books ever written. It records the course of Hazlitt’s passion for Sarah Walker, his landlady’s daughter, when the writer was 42 and the girl 19. The passion was unrequited and unfulfilled, and the embarrassment lies in the wealth of minor detail into which Hazlitt goes, recording every word and expression which passed between the two of them, and every impression that passed through his mind. His enemies had a field day with this tedious record of an infatuation worthy of an 18 year old boy, from the pen of an adult writer with 16 books to his credit.

First let me provide an example of its flavour.

H: Oh! is it you? I had something to show you—I have got a picture here. Do you know anyone it’s like?

S: No, Sir.

H: Don’t you think it’s like yourself?

S: No: it’s much handsomer than I can pretend to be.

H: That’s because you don’t see yourself with the same eyes that others do. [I] don’t think it handsomer, and the expression is hardly so fine as yours sometimes is.

S: Now you flatter me. Besides, the complexion is fair, and mine is dark.

H: Thine is pale and beautiful my love, not dark.

etc etc. (The conversations took place when Sarah entered the room in her capacity as maid.)

Hazlitt, I suspect, has always been convinced that he could never inspire passionate love in a woman. “I have wanted only one thing to make me happy,” he wrote recently, “but wanting that, have wanted everything.” It seems that what inspired his love for Sarah was the flirtatious look she gave him the first time they met—apparently her habit with new male lodgers.

Bryan Procter, a friend of Hazlitt who visited him at his lodgings, recalls that Sarah was a human blank slate. “Her eyes were motionless, glassy, and without any speculation (apparently) in them,” he observed. “She was silent or uttered monosyllables only, and was very demure. Her movements in walking were very remarkable, for I never observed her to make a step.” This, surely, is a description of the human equivalent of Stendhal’s “leafless wintry bough”, and Liber Amoris the crystallization that occurred on it. Hazlitt’s insecurity, which would only allow a purely fictitious love, required a subject, but one which would interfere not at all in the fiction, by either advancing or withdrawing with any assertion.

To know Hazlitt and to read Stendhal is almost like seeing the hand inside the glove. “Some people,” the Frenchman says in De l'Amour, “over-fervent, or fervent by starts, will hurl themselves upon the experience instead of waiting for it to happen. Before the nature of an object can produce its proper sensation in them, they have blindly invested it from afar with imaginary charm which they conjure up inexhaustibly within themselves. As they come closer they see the experience not as it is, but as they have made it. They take delight in their own selves in the mistaken belief that they are enjoying the experience. But sooner or later they get tired of making the running and discover that the object of their adoration is [not returning the ball]; then their infatuation is dispelled, and the slight to their self-respect makes them react unfairly against the thing they once overrated.” Thus was it with Hazlitt: at the end of Liber Amoris Sarah is described as vixen, witch and serpent.

I had one last long talk with Hazlitt just before he left Paris, and he was surprisingly open about himself. In the three months he had been in the city, his health had improved but he was still haggard, and I suspected he was reluctant to leave. He was headed in the direction of Italy and a travel book. I raised with him the subject of the curious gap between Stendhal’s idealistic—or, more properly, fantastical—notion of love and the frequency of his affairs of a purely physical nature. We were walking in the Place de la Concorde and Hazlitt slowed down, his eyes on the ground, and said carefully, as if this were a matter he had often considered: “Excessive refinement tends to produce equal grossness.”

“What!”

“The tenuity of our intellectual desires leaves a void in the mind which requires to be filled up by coarser gratification, and that of the senses is always at hand.”

As I was leaving, Hazlitt looked up and made a speech. “I am not in the ordinary acceptance of the term, [a good-natured man],” he said earnestly. “Many things annoy me besides what interferes with my own ease and interest.”

I suggested this would not come as a surprise to anyone.

”Good-nature, or what is often considered as such, is the most selfish of all the virtues,” he declared. “It is nine times out of ten mere indolence of disposition.” For a man of spirit, he said, “Nature seems made up of antipathies: without something to hate, we should lose the very spring of thought and action. Life would turn to a stagnant pool, were it not ruffled by the jarring interests, the unruly passions of men.”

“Most people might think differently.”

Hazlitt shrugged. “I have quarrelled with almost all my own friends,” he said, as if this settled the matter. He passed a hand through his hair and looked round the vast square, as if searching for something, or someone. “As for my old opinions, I am heartily sick of them. I was taught to think, and I was willing to believe, that genius was not a bawd—that virtue was not a mask—that liberty was not a name—that love had a seat in the human heart. Now I would care little if these words were struck out of my dictionary, or if I had never heard of them. I have been in my public and private hopes, calculating others from myself, and calculating wrong; always disappointed where I placed most reliance; the dupe of friendship, and the fool of love; have I not reason to hate and to despise myself? Indeed I do.” He laughed harshly. “And chiefly for not having hated and despised the world enough.”

Comments

No one has commented yet. Be the first!