[Read More]

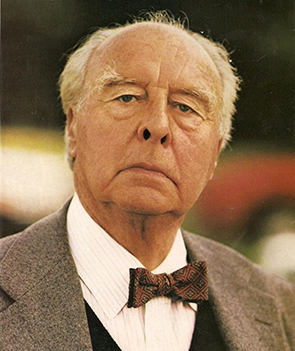

“It’s very peculiar, you know, that the only person who’s caught the Californian atmosphere in prose is an Englishman – Chandler,” Billy Wilder told me. The director worked recently with Raymond Chandler at Paramount. “He’s a very difficult man, a sort of rather acid man, like so many former alcoholics are.”

Did you share any jokes?

“Very rarely,” Wilder said with a laugh. “He would just kind of stare at me.”

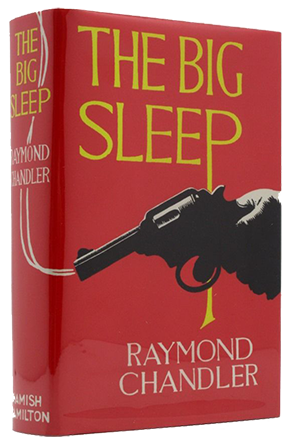

The taxi moves through the empty, tree-lined streets of La Jolla near San Diego. This is a wealthy neighbourhood, where Chandler and his wife Pearl have just bought a house, after decades of moving between rentals on an almost annual basis. The gradual success of his novels, starting with The Big Sleep in 1939, and the film of that novel released this year, have made this possible.

It’s a large house just across the road from the sea. The door is opened by a maid, who takes my hat and shows me into a large lounge room. There is a big window looking out at the Pacific, but the curtains are half-drawn against the midday sun. In the gloom sits a man, a woman, and a cat.

[Read More]

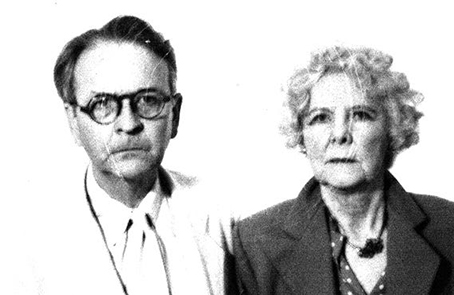

Chandler stands to say hello. He is 58, of medium height, has black wavy hair and eyes that seem eager to take offence. In a tweed jacket and grey flannels, he looks like a grumpy college professor. Pearl is 18 years older and an invalid, and remains seated. She is wearing a dress designed for a woman half her years, which emphasizes the gap in their ages. After we exchange greetings, they both stare at me in silence.

“Nice area,” I offer.

Chandler says it’s good not to be in Los Angeles, a “hard-boiled city with no more personality than a paper cup”. He says it almost defiantly, as though daring me to disagree. When I grunt and ask a question about something else, he looks mildly affronted.

The atmosphere in the room is close. Pearl starts to talk to the cat, nothing special, just asking if it feels hungry. But as Chandler stays silent and her voice rambles on, I begin to panic – not that I am completely unprepared for this unusual household. While preparing for the interview, I located very few people who actually knew the Chandlers, but those who did all emphasized a certain strangeness. Apparently, after they first met and started their affair, Pearl divorced her husband, but Raymond wouldn’t marry her until his mother died. They wed two weeks later and became loners, by most accounts, which might help explain their constant changes of address.

The cat chat dies away. A few more polite questions from myself receive shrugs and further silence, as though to emphasise their unfamiliarity with encountering other people. Chandler begins to fill his pipe and I notice his hands, like his face, are unnaturally pale, virtually white. He avoids my eyes and glances at the wall almost with despair, as though the whole idea of my visit is no longer welcome. Finally he announces that The Interview will take place after lunch, and we move into the dining room, Chandler walking as though there is something wrong with his joints.

Pearl seems to be drifting, but she makes it into the other room. One person I spoke to, in a position to know, says Pearl knocked ten years off her age before she married Ray. The friend says she’s still not sure if Ray knows his wife’s real age.

[Read More]

[Read More]

We sit down and Pearl explains with sudden brightness that they have a new cook: since buying this place a few months back they have had several cooks, but none of them has been clean enough. Hygiene would appear to be more desirable in their cook than culinary skills: the meat, when it arrives, is so tough it is barely edible. As we chew away, I recall the story that John Houseman told me yesterday, and wonder if I have found the right Raymond Chandler.

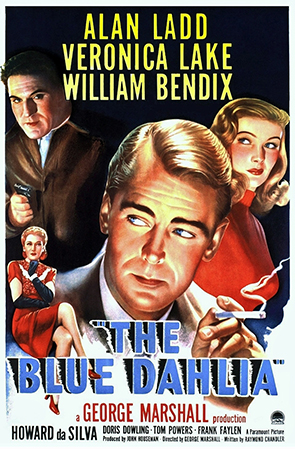

Houseman produced The Blue Dahlia, which has just been released to good reviews, and for which Chandler did the screenplay. The two men got on well together, partly because both had been to minor English public schools. Alan Ladd, the film’s star, was about to be drafted into the army, so there was a lot of pressure on everyone involved. Shooting began before the script was finished, and gradually caught up with it. Chandler was having trouble with the ending, and came into Houseman’s office one morning and said he could not finish the film.

Then, says Houseman: “After some prefatory remarks about our common background he made the following astonishing proposal. Alcohol gave him an energy and self-assurance that he could achieve in no other way. Ray assured me of his complete confidence in his ability to finish the screenplay at home—[drunk].” Chandler then produced a list of the help he wanted from the studio, typed neatly on a yellow half-foolscap sheet of paper. Houseman thought about it for a while and agreed.

The two men went out to lunch immediately and Chandler consumed three double martinis and three double stingers. Two weeks later, with the help of two limousines, six secretaries, daily vitamin injections and lots of bourbon, the screenplay was finished.

“It took him almost a month to recover,” Houseman recalls. “When I came to see him during his convalescence he would extend a white and trembling hand, and acknowledge my gratitude with the modest smile of a gravely wounded hero who had shown courage far beyond the call of duty.”

[Read More]

[Read More]

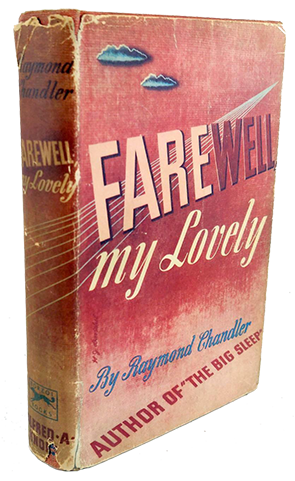

I want to emphasise the strangeness of Chandler because his books are strange too, far more so than most of their many fans seem to recognize. These days critics and fine writers, such as W.H. Auden and Evelyn Waugh, get excited about The Big Sleep, Farewell, My Lovely and their successors, which are full of dialogue, description and observations almost never before found in books of their kind. The combination of the mystery novel and a certain element of poetry is undoubtable new and entertaining. But there are a lot of flaws in the books, it seems to me – they are really strings of pieces of clever writing where the plot, and even the characterization, doesn’t bear too much examination. There is also quite a bit of nastiness – Chandler doesn’t seem to like homosexuals, or Negroes, or rich women. And then – we shall dwell on this later – there is the strange Philip Marlowe, more a voice than a character.

All this makes the creator of these strange concoctions of particular interest. With most writers it’s not hard to see the links between their character and life, and their work. I failed to do this with Chandler, except to establish that both are very weird. Here are a few observations.

Over lunch we chat in a desultory manner about Chandler’s childhood; he has come a long way. Born in Chicago in 1888, he was the son of an alcoholic father who ran off before he was seven. Ray was taken by his mother to be supported by rich but mean relatives and schooled in England. Later, living in London, he spent almost five years trying to become an Edwardian poet. His early work was sentimental – but then, so are the Philip Marlowe books, in their way. He says those years in London were “the age of taste, to which I once belonged. I could so easily have become everything our world has no use for.”

In 1912 he returned to America and became a bookkeeper, before seeing action on the Western Front in the Canadian army. He was promoted to acting sergeant before joining the Royal Air Force just before the war ended, after which he returned to America, his mother following.

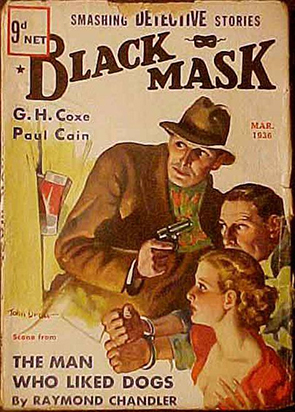

Chandler became an executive in an oil company but started to drink heavily and have office affairs. His emotional problems led to absenteeism and threats to commit suicide. He was fired in 1932 and decided to join the ranks of America’s 1,000 pulp writers. The popular mystery story magazine Black Mask accepted his first effort.

The drunken oil executive, and the writer described by John Houseman from earlier this year, are unrecognizable now. It is a strangely formal meal for lunch in California, yet there is no alcohol. Afterwards, Pearl retires to her bedroom and Chandler and I sit down to talk.

Chandler’s admirers rightly applaud the wit and style in his work, but perhaps its strongest feature is the fact that while he seems to be writing about one sort of man, the knight in shining armour, Philip Marlowe is a more complex character. For such a bruiser, he is a strangely pernickety fellow, with his attention to domestic and sartorial detail. In his descriptions of women the stylist dominates the man. There is lots about clothes, and the details of hairstyles, and relatively little about bodies and their immediate effect on Marlowe.

[Read More]

Consider, for example, the description in Farewell, My Lovely of the body of Mrs Grayle. She is apparently one of the most beautiful women Marlowe has ever met, yet even here his description is restrained. “Her hair was of the gold of old paintings . . . She had a full set of curves which nobody had been able to improve upon . . . Her hands were not small, but they had shape . . .” This is adequate but perfunctory. Mrs Grayle is the woman who, in one of Chandler’s most famous lines, would “make a bishop kick a hole in a stained-glass window”, but you’d never guess it from that physical description.

It’s possible that Chandler is being coy in such passages as a deliberate reaction against the salacious descriptions of women more common in pulp fiction. But he doesn’t hold back in some of his descriptions of men. Here for example is Red, a speedboat driver and minor character from the same book. “He had the eyes you never see, that you only read about. Violet eyes. Almost purple. Eyes like a girl, a lovely girl. His skin was as soft as silk. Lightly reddened, but it would never tan. It was too delicate . . . His hair was that shade of red that glints with gold. But except for the eyes he had a plain farmer face, with no stagy kind of handsomeness.”

Marlowe is a great chatterer, who almost takes delight in provoking big tough men, sometimes so they beat him up. Despite this, many of the murders he investigates turn out to have been committed by women. Mrs Grayle, for instance, bludgeons one man to death with a blackjack and kills two more with a gun.

It seems to me there is a lot more going on here – but I can’t say what. I have a friend who suggests Marlowe is homosexual, despite the disdain for such men in the books, but that doesn’t seem to me the obvious conclusion – although it’s true that his cute patter never leads anywhere with women.

The characteristic that does strike me most about Marlowe is his general solitariness – not only does his chosen profession encourage this, he appears to have no background, including no family. His social context is, to put it mildly, vague.

Marlowe has no friends, of either gender. This fits in with his generally wary attitude to other human beings, whether they be plutocrats or clients. Is this a cynicism born of experience, or is it something else? His enthusiasm for justice seems as much a way of keeping distance as a positive virtue. He is more an attitude, a voice – the books are in the first person – than a character. This focus on verbal style has its problems, but enables a certain freedom of action, and expression. The poetry slips free of earthly bounds.

The interview begins and I ask Chandler about Marlowe, but tangentially. Is he, I say, intended to be realistic?

Chandler looks at me as though I’m mad, but at least I’ve gained his attention.

“In real life a man of his type would no more be a private detective than he would be a university don,” he agrees. “Your private detective in real life is usually either an ex-policeman with a lot of hard practical experience and the brains of a turtle or else a shabby little hack who runs around trying to find out where people have moved to.”

[Read More]

[Read More]

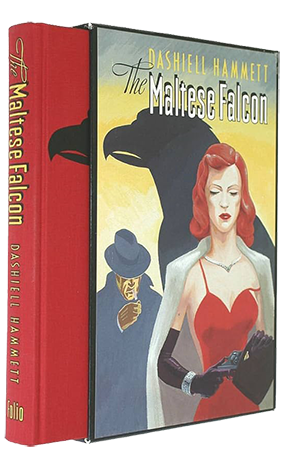

Then, abandoning Marlowe for the moment, he talks about Dashiell Hammett, whose books, such as The Maltese Falcon, opened the way for Chandler’s own work, with their realistic settings and use of American language. This approach was encouraged by Black Mask magazine.

Until then, he notes, “The emotional basis of the standard detective story was and had always been that murder will out and justice will be done. Its technical basis was the relative insignificance of everything except the final denouement. What led up to that was more or less passage-work. The denouement would justify everything.” However, “The technical basis of the Black Mask type of story was that the scene outranked the plot in the sense that a good plot was one which made good scenes. The ideal mystery was one you would read if the end was missing.”

Certainly this is true of his own work, which in my experience – and unlike most crime fiction – reveals new pleasures on rereading. But this is on account of the language, not the plots, which are often incomprehensible. Hence the famous story about director Howard Hawks, when filming The Big Sleep, cabling Chandler to ask who killed the chauffeur, Chandler cabled back: NO IDEA. The point to the story is that it didn’t matter. As Chandler told me, it’s the scene that counts. And in his books, the scene can have strangely little connection to either character or plot.

This is not a criticism. It is, I suppose, a suggestion that he has created a new kind of book.

Trying to get back on track, I ask if he had a clear idea of Marlowe when he first invented him. Marlowe, he says, “is neither tarnished nor afraid . . . He must be a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man. He must be, to use a rather weathered phrase, a man of honour.”

In terms of social context, I begin, and Chandler interrupts: “He is a relatively poor man, or he would not be a detective at all. He is a common man or he could not go among common people. He is a lonely man – ” Why, I ask. Why does he have to be a lonely man? Chandler stares at me as though he doesn’t understand the question, or else finds it preposterous. I have the sense he might terminate the interview.

Take women, I begin again. There’s a lot of scenes in the books where Marlowe declines to have sex with women who are hungry for him. He seems to be attracted to them in the abstract, but not the actual. “I do not care much about his private life,” Chandler mutters, a strange admission from a novelist. Then, as though realising this and seeking to refine it, he adds, “He is neither a eunuch nor a satyr. I think he might seduce a duchess and I am quite sure he would not spoil a virgin.” It’s a clumsy evasion of the question, and interesting that it takes us well away from American language and back to his Edwardian youth. “If he is a man of honour in one thing, he is that in all things.”

Chandler smiles for the first time since I arrived. Waving his pipe, he announces our interview is almost over. Cissy – his name for his wife – has a doctor coming at three. This is stated with utter seriousness, as though his wife’s medical timetable is the determinant of the household’s very existence.

I ask about the focus on corruption in the books; the question appears to interest him.

“Outside of two or three technical professions which require long years of preparation,” he declaims, “there is absolutely no way for a man of this age to acquire a decent affluence in life without to some degree corrupting himself, without accepting the cold, clear fact that success is always and everywhere a racket.” I want to expostulate, to argue that while this is a bit true, it does not explain the world as comprehensively as he’s asserting. But I see he believes it passionately, necessarily. Possibly Chandler, like many an artist, is wise enough not to challenge the sources of his motivation.

[Read More]

Anyway, this is an interview, not a debate. And we are running out of time.

He’s already told me he knew no writers when he started out, and I ask how he learned the trade. He says he used to be a journalist, in England, and that to be a writer you need to read, constantly. “A schoolmaster of mine long ago said, ‘You can only learn from the second-raters. The first-raters are out of range; you can’t see how they got their effects.’ There is a lot of truth in this.” After a pause he adds, “Any writer who cannot teach himself cannot be taught by others.”

“How do you do that?” I ask. “Teach yourself.”

“Analyze and imitate; no other school is necessary. Never take advice. Never show or discuss work in progress. Never answer a critic.”

It is an introvert’s guide to writing. In fact, I’ve never met an author who lived in such professional isolation. He seems at times actively to dislike other authors, possibly a hangover from his unsuccessful attempts to break into the London literary world. “The English may not be the best writers in the world,” he says at one point, discussing certain well-known mystery writers across the Atlantic, “but they are incomparably the best dull writers.” Later he murmurs that authors generally “live overstrained lives in which far too much humanity is sacrificed to far too little art.”

We talk about the fact he began writing late in life, and he offers: “In every generation there are incomplete writers, people who never seem to get much of themselves down on paper, men whose accomplishment seems always rather incidental. Often, but not always, they have begun too late and have an over-developed critical sense. I guess maybe I belong in there.”

[Read More]

It is an interesting admission, obviously something he wanted to get into the interview, as though it’s been playing on his mind. Does he mean by this, I ask tentatively, that he might try writing something other than the mystery novel? He says one way out of the dilemma could be to expand the boundaries of the genre even more than he has done.

I’m interested to learn more, but there is a knock on the front door, and Chandler jumps: I know immediately that the interview is over. He says goodbye, and I say thank you, confessing that I’ve wanted to meet ever since the esteemed critic Edmund Wilson praised him in the New Yorker last year. Chandler’s eyes light up with pleasure, and he shrugs beneath his tweed jacket.

“What greater prestige can a man like me have,” he says as we stand up, “than to have taken a cheap, shoddy, and utterly lost kind of writing, and have made of it something that intellectuals claw each other about?”

The maid has answered the front door and I pass the doctor in the hallway, a large man accompanied by a nurse in uniform, carrying his black leather bag. He looks expensive.

Comments

No one has commented yet. Be the first!