[Read More]

[Read More]

I first met Gustave Flaubert while visiting Carthage in North Africa. There hasn’t been a lot to see at Carthage since the Romans razed it in 146 BC, but it has a romantic appeal for lovers of ancient history. It turned out the notorious novelist shared my enthusiasm, and in fact was researching a historical novel, Salammbô. Despite the desolation, he was glad at last to be on the spot.

“I have indigestion from book reading,” he laughed.

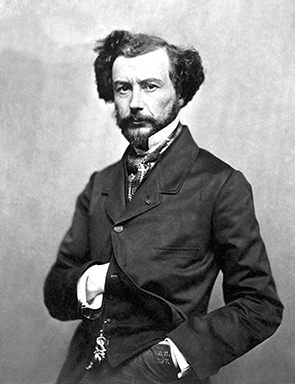

Flaubert was a big man, with large, protruding eyes, full cheeks, a rough moustache, and a red-splotched complexion. That night we spoke after dinner, our tents being pitched not too far from each other. He did not want to talk about his current project, and instead spoke about something else entirely.

Apparently he had long harboured an ambition to write a Dictionary of Accepted Opinions, which would be a list of cliches, “the historical glorification of everything generally approved.” It would cover all possible subjects, he added, and include “everything one should say if one is to be considered a decent and likeable member of society.”

This was unexpected.

“What a grotesque idea,” I said; my comment seemed to make him happy.

“For me the tragic grotesque holds immense charm,” he responded with some eagerness, “it corresponds to the intimate needs of my nature, which is buffoonishly bitter. It doesn’t make me laugh, but sets me dreaming.” He looked out at the dry landscape and stretched his arms. “Almost all human beings are endowed with the gift of exasperating me, and I breathe freely only in the desert.”

Of course I had read Flaubert’s first published book, Madame Bovary, when it appeared as a series in the Revue de Paris two years before. The book, about the perils of dreaming, was an enormous success, and had been put on trial for obscenity. Flaubert told me that, after quoting some passages from the text, the prosecutor had asked the judges: “Gentlemen, do you know of language anywhere in the world more expressive?”

He snorted with laughter. “And this,” he said, tugging my sleeve. “He said, ‘The author does not endeavour to follow such or such a system of philosophy, true or false. He endeavours to produce certain pictures, and you shall see what kind of pictures!’”

“What pictures indeed,” I murmured, recalling scenes of amputation, folly, and, in a description of a tryst combined with an agricultural fair, the most moving piece of prose I have ever experienced. Rarely has one book made its author’s reputation so suddenly.

Flaubert seemed to appreciate my observation.

“You do not have a system of philosophy?” I asked.

He shuddered. “It’s easy, with the help of conventional jargon, and two or three ideas acceptable as common coin, to pass as a socialist humanitarian writer, a renovator, a harbinger of the evangelical future dreamed of by the poor and the mad. Now every piece of writing must have its moral significance, must teach its lesson, elementary or advanced; a sonnet must be endowed with philosophical implications, a play must rap the knuckles of royalty, and a water colour contribute to moral progress. Everywhere there is pettifoggery, the craze for spouting and orating: the muse becomes a mere pedestal for a thousand unholy desires.”

The next day he was on his horse by dawn, but later on I came across him a few kilometres from our campsite. He was sketching some sort of map, and I sat next to him and began to smoke.

“I love history, madly,” he announced. “The dead are more to my taste than the living.”

He looked at me fiercely, as if expecting a response. I confess to being overwhelmed by Flaubert’s presence, completely inadequate. If we had not been alone in the middle of the wilderness, I would have avoided him. As it was, I murmured something about the problems of the times.

“I feel waves of hatred for the stupidity of my age,” he cried with sudden fury. “They choke me. Shit keeps coming into my mouth, as from a strangulated hernia. I want to make a paste of it and daub it over the nineteenth century.” Pause. “We are dancing not on a volcano, but on the rotten seat of a latrine. Before very long, society is going to drown in nineteen centuries of shit.”

“I blame it on the steam engine,” I suggested, trying to move the conversation on from the scatological.

“Speaking of industry,” he cried, changing subject with the speed I realised must be part of his nature, “have you sometimes thought of the quantity of stupid professions it begets, and the vast amount of stupidity that must inevitably accrue from them over the years? What can be expected of a population like that of Manchester, which spends its life making pins? And the manufacture of a pin involves five or six different specialities! As work is broken down into compartments, men-machines take their places besides the machines themselves. Yes, mankind is becoming increasingly brutish.”

*

When I met Flaubert he was 37, having been born in Rouen in 1821. His father was a famous surgeon; on leaving school, Flaubert junior was sent to Paris to study law. He hated it, and failed the first year exams. Early in the second year he had his first attack of epilepsy.

“Each attack was like a haemorrhage of the nervous system, a snatching of the soul from the body,” he told me.

The cure for this was rest and maternal care – and no more law. Two years later his father died, and he had lived with his mother ever since, in Rouen and now Croisset. She did not like him travelling, although he visited Paris several times a year.

When he was 25 he met the poet Louise Colet, who became his mistress. She was 11 years his senior. He told me he would never marry. “There are few people who do not become bourgeois at 30,” he explained. “Paternity would have relegated me to the ordinary condition of life. My innocence in relation to the world would have been destroyed, and that would have cast me into the pit of common miseries. If you participate in life, you don’t see it clearly: you suffer from it too much or enjoy it too much. The less you feel a thing, the more capable you are of expressing it as it is.”

[Read More]

[Read More]

Flaubert had two good friends in his youth, Maxime DuCamp and Louis Bouilhet. When he was 28 he read them a vast philosophical work he had written, La Tentation de Saint Antoine. When I was next in Paris I visited DuCamp and asked him about this.

“The hours that Bouilhet and I spent listening to Flaubert chant his lines—we sitting there silent, occasionally exchanging a glance—remain very painful in my memory,” he said. “We kept straining our ears, always hoping that the action would begin, and always disappointed, for the situation remains the same from beginning to end. St. Anthony, bewildered, a little simple, really quite a blockhead if I dare say so, sees the various forms of temptation pass before him and responds with nothing but exclamations: ‘Ah! Ah! Oh! Oh! Mon dieu! Mon dieu!’ Flaubert grew heated as he read, and we tried to grow warm with him, but remained frozen. After the last reading—it was almost midnight—Flaubert pounded the table: ‘Now: tell me frankly what you think.’”

DuCamp shook his head sadly. “Bouilhet is a shy man, but no one is firmer than he once he decides to express his opinion, and he said: ‘We think you should throw it into the fire and never speak of it again.’” He grimaced. "Mme Flaubert long held our frankness against us. She thought we were jealous of her son.”

Flaubert spent the next five years writing Madame Bovary, and then submitted it to DuCamp , who told him it was “a muddled work to which the style alone does not give sufficient interest. You have buried your novel under a heap of details which are well done but superfluous.” He urged his old friend to allow him to hand the manuscript over to a good editor. Flaubert refused and DuCamp relented, agreeing to publish the novel as it was, except for the scene describing Emma's erotic cab ride through the streets of Rouen. As the serialisation progressed, the government censor asked the department of justice to prosecute the author and the magazine for “outrage of public morals and religion”, and a number of other passages were cut without Flaubert’s permission.

His reputation was made.

*

The next morning I rose early and found the great man shaving before a small mirror.

“I have deteriorated shockingly,” were his words of greeting. “There are mornings when I am afraid of myself, I am so wrinkled and worn. Ah! There were only two or three years in my life—approximately from seventeen to nineteen—when I was entire. I was splendid.”

I shaved silently and Flaubert asked if I was missing my fiancee, of whom I had spoken last night. I told him I was.

“As far as literature is concerned, women are capable only of a certain delicacy and sensitivity,” he told me kindly, and with no relevance that I could see, except to himself and his obsessions. “Everything that is truly sublime, truly great, escapes them. Our indulgence toward them is one of the reasons for the moral abasement that is prostrating us. Never pay any attention to what they say about a book. For them, temperament is everything—the occasion, the place, the author . As for knowing whether a detail (exquisite or sublime in itself) strikes a false note in relation to the whole—no! A thousand times no!”

“Well, Isabelle is not—”

“That may sound cynical to you—”

“It does.”

“—but human nature is not my invention.”

“Surely Louise Colet—”

[Read More]

[Read More]

“Women who have loved a great deal do not know love,” he told me passionately, perhaps remembering one of Colet’s novels in which he had appeared, not to best advantage. “They have been too immersed in it; they do not have a disinterested appetite for the Beautiful. For them, love must always be linked with something, with a goal, a practical concern. They write to ease their hearts—not because they are attracted by Art, which is a self-sufficient principle, no more needful of support than a star.”

He left the next day, inviting me to call on him should I ever be in the neighbourhood of Croisset.

When I reached Paris some months after this I called on Louise Colet. She was bitter – their affair had ended - and said she would not talk of him. Then she opened a drawer and took out a diary, and read aloud.

“1852. His seizure at the hotel. My terror. He begs me not to call anyone. He foams at the mouth: my arm is bruised by his clenched hands and nails. In about ten minutes he comes to himself. Vomiting. I assure him the attack lasted only a few seconds, and that there was no foaming.”

She put down the diary and indicated the interview was at an end. As I was leaving she told me DuCamp had said to her that Flaubert was a “being apart, perhaps a non-being”.

The next day I met Edmond de Goncourt, literary man about town, who told me the hermit of Croisset had a kindly face but, “Though perfectly frank by nature, he is never wholly sincere in what he says he feels or suffers or loves.”

This, it seemed to me then, was outrageous.

I wrote to Flaubert, asking for an interview to be published in an obscure magazine called Reading Project – a publication in, of all places, the English colony of New South Wales. It was – and still is - a beacon of good taste and insight, although not well known in the metropolitan centres. But a copy I’d sent met with his approval.

So he invited me to his home. Of his work on the Carthage novel he wrote: “I’ve finally achieved the erection, Monsieur, by dint of self-flagellation and masturbation. Let’s hope there’s joy to come.”

Taking this curious description of literary production as good news, I went to stay with some friends near Saumer, and then made my way into Normandy and Croisset.

Flaubert lived in a long white house on the banks of the Seine. When I arrived and opened the iron gate, the yellow leaves were falling on the river. I walked up the path, and as I waited by the door, looking towards the river, a steamer passed. Flaubert’s mother greeted me, and I was shown into a large study with five windows, in which comfortable green armchairs faced a good fire. The novelist, wearing a silk skullcap, was pacing up and down. He greeted me restlessly, pointing to the library around him: “Me and my books, in the same apartment: like a gherkin in its vinegar!”

We talked a bit, and it emerged that he had read a newspaper that morning, for the first time in a while, and this had depressed him. There had been news of some literary prize or other.

“Have you ever remarked how all authority is stupid concerning Art?” he told me. “Our wonderful governments (kings or republics) imagine that they have only to order work to be done, and it will be forthcoming. They set up prizes, encouragements, academies, and they forget only one thing, one little thing without which nothing can live: the atmosphere.”

And so to the questions.

“What are the three best things in the world?”

“The three finest things that God ever made are the sea, Hamlet, and Mozart’s Don Giovanni.”

“What is good art?”

“The finest works are those that contain the least matter. What mind worthy of the name [of artist], starting with Homer, ever reached a conclusion?” Pause. “What seems to me the highest and most difficult achievement of Art is not to make us laugh or cry, nor to arouse our lust or rage, but to do what nature does—that is, to set us dreaming.”

I was used to Flaubert’s pauses by now—often they indicated the preparation of a thought that would qualify or even contradict the one that had gone just before.

“Is good art beautiful?”

“It is so easy to chatter about the Beautiful. But it takes more genius to say, in proper style: ‘Close the door,’ or ‘He wanted to sleep’. Pause. “The time for beauty is over. Mankind may return to it, but has no use for it at present. The more Art develops, the more scientific it will be, just as science will become artistic. Separated in their early stages, the two will become one again when both reach their culmination.”

Sometimes, I thought, his views of reality were so wild it was fortunate he was a great novelist.

[Read More]

I asked a question inspired by the Romantic proclivities of the first part of our century.

“Should a writer be his own subject?”

“There are writers whose slightest cry is melodic, whose every tear wrings the heart, and who have only to speak of themselves to remain eternal. Byron belongs to this class. Yet Art must rise above personal affections and neurotic susceptibilities! The artist in his work must be like God in his creation,” Flaubert exclaimed, “invisible and all-powerful. He must be everywhere felt, but never seen. It is time to banish anything of that sort from it, and give it the precision of the physical sciences." Pause. “Homer, Rabelais, Michelangelo, Shakespeare and Goethe seem to me pitiless. They are unfathomable, infinite, manifold. Through small apertures we glimpse abysses whose sombre depths turn us faint. And yet over the whole there hovers an extraordinary tenderness.” Pause. “I think the greatest characteristic of genius is power. Hence, what I detest most of all in the arts, what sets me on edge, is the ingenious, the clever.

“Shakespeare frightens me the more I think of him. In their entirety, I find his works stupendous, exalting, like the idea of the planetary system. The greatest, the rare true masters, are microcosms of mankind: not concerned with themselves or their own passions, discarding their own personality, they are, instead, absorbed in that of others; they reproduce the Universe, which is reflected in their works, scintillating, varied, manifold, like an entire sky mirrored in the sea with all its stars and all its azure. When I have reached the crest of one of his works I feel that I am high on a mountain: everything disappears, everything appears. I am no longer a man, I am an eye.”

“Who is your ideal reader?”

“One must write for oneself, first and foremost. Only that way does one stand a chance of producing something good.”

“Do you enjoy writing?”

“Sometimes, when I am empty, when words don’t come, when I find I haven’t written a single sentence after scribbling whole pages, I collapse on my couch and lie there dazed, bogged in a swamp of despair, hating myself and blaming myself for this demented pride that makes me pant after a chimera. A quarter of an hour later, everything has changed; my heart is pounding with joy. Last Wednesday I had to get up and fetch my handkerchief; tears were streaming down my face. I had been moved by my own writing: the emotion I had conceived, the phrase that rendered it, and the satisfaction of having found the phrase—all were causing me the most exquisite pleasure.” Pause. “Few men, I think, will have suffered as much as I for literature.”

Food arrived and we ate, in my case with great hunger. Flaubert paused, with a forkful of meat halfway to his mouth. “Prose was born yesterday, you have to keep that in mind. Verse is the form par excellence of ancient literatures. All possible poetic variations have been discovered; but that is far from being the case with prose.”

“How close did you become to Emma?”

I was thinking of Baudelaire’s comment, published somewhere, that “Madame Bovary, in the most energetic and ambitious aspects of her character, and also in her strong predilection for reverie, remained a man.”

“The characters I create drive me insane,” he said now, “they haunt me; or rather, I haunt them: I live in their skin. When I was writing about Madame Bovary taking poison, I had such a distinct taste of arsenic in my mouth that I had two attacks of indigestion, one after the other—I vomited my entire dinner.”

“Could you imagine any other life for yourself?”

“The thing is to keep fucking, keep fucking: who cares what child the muse will give birth to? Isn’t the purest pleasure in her embraces?”

An obvious note on which to end. But, I think, the right one.

Comments

No one has commented yet. Be the first!