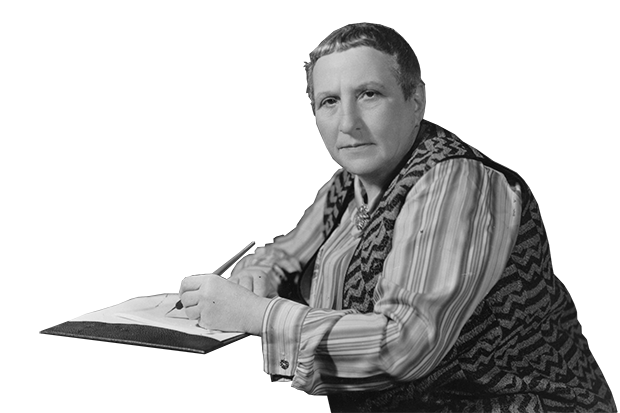

We are at her house, 27 rue de Fleurus in Paris. I ask if she enjoyed last year. She says she did.

“I got very much interested in reporters. Reporters are mostly young college men who are interested in writing and naturally I was interested in talking with them. Once it may have been in Cleveland or Indianapolis, I was talking there were two or three of them and a photographer with them and I said you know it is funny but the photographer is the one of the lot of you who looks as if he were intelligent and was listening now why is that, you do I said to the photographer you do understand what I am talking about don’t you.”

Gertrude Stein does talk like this, and the transcript of our conversation defies conventional punctuation.

“Of course I do he said you see I can listen to what you say because I don’t have to remember what you are saying, they can’t listen because they have got to remember.”

I suggest, “All young reporters want to become writers—”

“Newspaper people never become writers,” she responds sternly, “because they have a false sense of time. Three senses of time they have to struggle with, the time the event took place, the time they are writing, and the time it has to come out. Hemingway, on account of his newspaper training, has a false sense of time.”

“Why don’t you live in America? You’re obviously fond of it.”

“Your parents’ home is never a place to work it is a nice place to be brought up in. Later on there will be place enough to get away from home in the United States, it is beginning, then there will be creators who live at home.”

I make some comments about the New World and the Old and she smiles tolerantly and informs me that actually America is the oldest country in the world, because “by the methods of the Civil War and the commercial conceptions that followed it America created the twentieth century, and since all the other countries are now either living or commencing to be living a twentieth century life, America having begun the creation of the twentieth century in the sixties of the nineteenth century is now the oldest country in the world.”

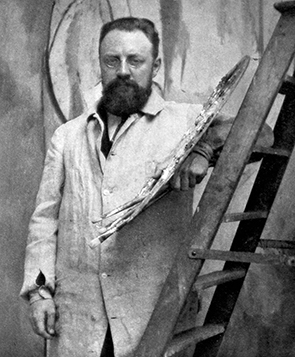

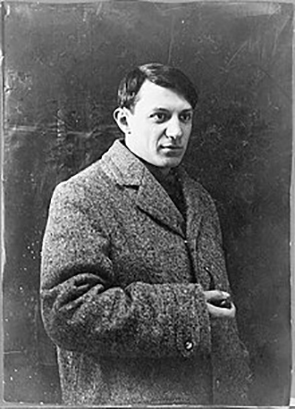

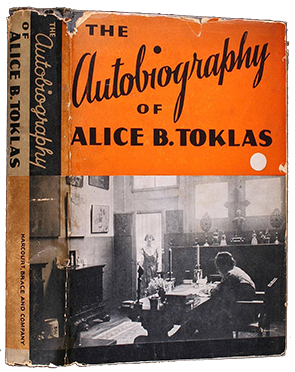

Miss Stein settled in Paris with her brother Leo in 1903, at the age of 29. She had a private income, $150 per month, and Leo and she bought paintings and became friendly with many artists. She says that it was Leo and she who introduced Picasso and Matisse to each other.

“They exchanged pictures as was the habit in those days,” she recalls. “Each painter chose the one of the other one that presumably interested him the most. Matisse and Picasso chose each one of the other one the picture that was undoubtably the least interesting either of them had done. Later each one used it as an example, the picture they had chosen, of the weaknesses of the other one.”

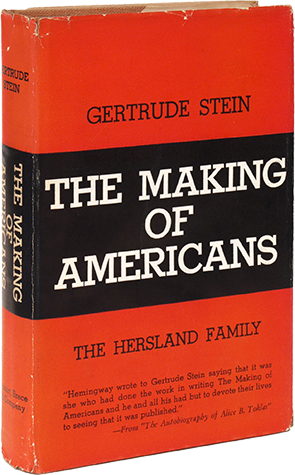

The American writer Robert McAlmon first published Stein’s The Making of Americans in book form, and arguments over the publication ended their friendship.

“Miss Stein is apparently interested only in people who sit before her and listen,” he recalls, and even claims that she once said to him: “Sometimes I wonder how anybody can read my work when I look it over after a time. It seems quite meaningless to me.”

I doubt the woman I am interviewing would ever say anything like that, although I lack the courage to ask. Few of Stein’s friendships with artists seem to have lasted—these days Braque, who owes so much to her, says unkindly that in her relationship with the art in Paris before the War, “she never went beyond the stage of a tourist.”

We talk about the novel as a form, and Stein surprises me by saying it hasn’t been very successful this century. I ask her why.

“This is due in part to this enormous publicity business,” she says. “The Duchess of Windsor was a more real person to the public and while the divorce was going on a more actual person than anyone could create. Then Eleanor Roosevelt is an actuality more than any character in the twentieth century novel ever achieved. People now know the details of important people’s daily life unlike they did in the nineteenth century. Then the novel supplied imagination.”

This is depressing. I ask her: “Is anything interesting about modern literature?”

“The only serious effort that has been made is the detective story, and in a kind of a way [Edgar] Wallace is the only novelist of the twentieth century. He created an atmosphere of crime and did not have characters that people worried about.” She stops talking for a minute and stares, then tells me about meeting Dashiell Hammett in Beverly Hills during her recent lecture tour. “I said to Hammett there is something that is puzzling. In the nineteenth century the men when they were writing did invent all kinds and a great number of men. The women on the other hand never could invent women they always made the women be themselves seeing splendidly or sadly or heroically or beautifully or despairingly or gently, and they never could make any other kind of woman. From Charlotte Bronte to George Eliot and many years later this was true. Now in the twentieth century it is the men who do it. The men all write about themselves, they are always themselves as strong or weak or mysterious or passionate or drunk or controlled but always themselves as the women used to do it in the nineteenth century. Now you yourself always do it now why is it. He said it’s simple. In the nineteenth century men were confident, the women were not but in the twentieth century the men have no confidence and so they have to make themselves as you say more beautiful more intriguing more everything and they cannot make any other man because they have to hold on to themselves not having any confidence.”

Stein studied medicine in her youth. There is a story that she refused to do the work necessary to pass her final exams, and when a fellow female student begged her to remember her duty to set an example to other women, Stein replied: “You don’t know what it is to be bored.” I ask her if she thought there could be as many great women writers as men, if only they had the confidence.

“One does not, no one does not in one’s heart believe in mute inglorious Miltons,” she tells me almost severely. “If one has succeeded in doing anything one is certain that anybody who really has it in them to really do anything will really do that thing.”

It is time to go. I close my notebook and stand up. I have the feeling Stein would like the interview to continue.

“What are you interested in?” I ask.

“To me when a thing is really interesting it is when there is no question and no answer. Anything for which there is a solution is not interesting. The things not that can be learnt but that can be taught are not interesting.”

“What do you do with your time these days?”

“It takes a lot of time to be a genius, you have to sit around so much doing nothing, really doing nothing.”

“You’re quite sure you are a genius?”

“Einstein was the creative philosophic mind of the century and I have been the creative literary mind of the century.”

Comments

No one has commented yet. Be the first!