- Category:Historical Fiction

- Date Read:7 January 2020

- Pages:469

- Published:2010

- Prize:Commonwealth Writers' Prize (South Asia and Europe) 2011

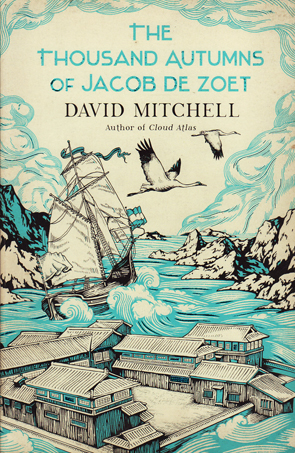

I have to confess; I have a small history with this book beyond the reading of it over the past two weeks. I bought the novel when it was published in 2010. Like a magpie attracted by the allure of blue pegs on a clothes line, I was drawn by its unusual and beautiful cover (the covers of later editions have been less so). In the style of a traditional Japanese print, it features a seascape with a trading boat buffeted by waves setting out from a trading post, perhaps the Dejima trading post of this story. On the back cover a traditional Japanese temple is featured. I don’t normally speak about covers in reviews, but it’s one of my favourites and I think it captures some of the mood of the story. I began reading the novel in 2010 and was almost halfway through when I abandoned it. I was intrigued by the story of Jacob de Zoet, a trading clerk in the Dutch trading post on Dejima island, just outside Nagasaki at the end of the eighteenth century, but life and work got in the way and I put the book down. Reading it does take some commitment and time which I didn’t have that year.

In between then and now I read another of David Mitchell’s books. No, not Cloud Atlas, although I have seen the film. That’s for a future read. Instead, I read the much shorter Slade House, a horror story set in the eponymous house, which I thought was terrible. Despite Mitchell’s reputation, that book prejudiced me against reading him again until I was told I just had to read Cloud Atlas, which led to my decision to return to this book first.

Which brings me to the obvious question rather quickly: what did I think of The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet? The answer is, I quite liked it. Despite having read almost half the book years ago, I was still surprised by the turn that the narrative takes shortly after where I originally left the book, and it drew me in.

The story begins in 1799 on Dejima, an island just off the coast of Nagasaki, which has been adapted as a trading post and customs port between the Dutch and Japan. Japan is an entirely isolated nation, with only this one small window to the outer world. Except for the highest-ranking officials, the Dutch are not permitted beyond the land gate that connects Dejima to greater Japan. Nor are they permitted to be taught Japanese and are forbidden to proselytise. They cannot even carry personal religious items like Bibles or psalters for their own use. In fact, Jacob de Zoet fearfully hides his family psalter when he knows Dutch quarters are to be searched by the Japanese.

The novel is a fairly traditional narrative, despite Mitchell’s reputation for experimentation. It is told in third person with a linear timeline, although most of it is in present tense. The story is mostly covered by three main parts (there are two short concluding sections also), each focussing on specific characters. In the first part, Jacob de Zoet, new to Dejima, witnesses the fall of Snitker, a corrupt company man due to be sent back to Batavia where he is meant to be tried. Jacob is tasked with the job of reconstructing the company accounts based upon the fragments of evidence from most of the last decade of trading in Dejima. Jacob hopes to make a good impression on Vorstenbosch, the Dutch Chief Resident and his deputy Melchior Van Cleef, and thereby win favour for a promotion. Added to this, he has a personal stock of mercury, well within the legal trading limits, to sell to the Japanese, hoping to make his fortune during his five-year tenure in the hope that he might return home rich enough to win the approval of his sweetheart’s father, and marry.

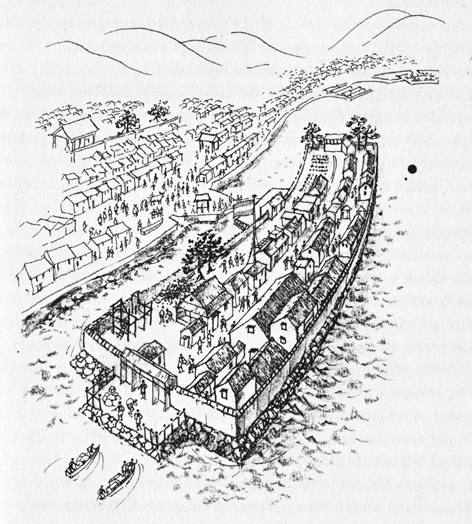

The island of Dejima, as illustrated in the novel. The land bridge to the Japanese mainland can be seen just behind the flag.

But this is really only the premise of the novel. Mitchell weaves several other narratives into this story. In fact, the novel begins with Orito Aubigawa, a Japanese midwife who saves the life of Magistrate Shiroyama’s concubine, Kawasemi, who is subjected to a gruelling ordeal when her child becomes breached with its arm hanging from her vagina. Miraculously, Orito manages to save the child along with its mother, even after all hope had otherwise been lost. Orito is an intelligent woman whose beauty has been marred by a burn on her face. Nevertheless, Jacob falls in love and begins to make advances towards her, despite the restrictions against interracial relationships in Japan. Yet, when Orito’s father dies her family is left destitute and her chance of happiness with Jacob is thwarted when they sell her to a Shrine which exploits its women in terrible ways.

The final strand of the story introduces Penhaligon, Captain of the English frigate Phoebus. Almost crippled with gout, Penhaligon sees Dejima as possibly his last hope to win glory for himself and secure his pension by taking Dejima from the Dutch and establishing the port as an English post.

What is important in all this is that The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet is both an entertaining novel as well as a novel of ideas. One can imagine it being adopted by Hollywood (although I know of no plans to do this) in much the way that World War Z, also a novel of ideas (believe it or not if you haven’t read it), was reduced to a hero-narrative starring Brad Pitt. That adaptational style would emphasise the women to be rescued in this story and the heroism of Jacob de Zoet against the British. After all, its historical context justifies the derring-do of samurai warriors on our modern screens, when watching women portrayed as helpless damsels in need of rescue has become just a little bit discomforting, otherwise, and just about every modern Hollywood film needs a male hero protagonist. But the book might also be adapted as something more artful, like Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon in which Ang Lee’s portrayal of traditional China was like a beautiful canvas, while also drawing from more mainstream martial arts movies. Added to that, it also empowered its female protagonist. Orito Aibagawa is deserving of such treatment if a movie ever does get made from this book, just as eighteenth-century Japan as portrayed by Mitchell deserves something subtler than Hollywood might otherwise provide. Having been entrapped in a terrible situation due to her family’s poverty – it’s like the East meets The Handmaid’s Tale, except worse – Orito not only has the nous to save herself, but has the integrity to consider the well-being of other women she would be abandoning if she did so. I think this is an important consideration, since much of the narrative – Jacob’s love for Orito and the story of his love-rival, Uzaemon Ogawa, set against the historical impetus that is sweeping Japan into the modern world – is structured around Orito’s fate.

But Mitchell’s narrative also raises some interesting considerations. Japan at the end of the eighteenth century is a highly isolated country. It’s dealings with the Dutch are shrouded with mystery and mistrust and the Dutch, for their part, are manipulative and highly dishonest as they try to wrest further trading concessions from the Japanese each year. Isolationism makes the Japanese vulnerable to a rapidly changing world they do not understand. Meanwhile, the Dutch remain highly vulnerable to the vagaries of the almost lawless nature of eighteenth-century trade. The distances between nations, where a fast ship is the fastest means of communication, leads to isolation from family, country and culture, often for years at a time. Attempts by either party to resist change, to remain culturally and intellectually static, as it were, seems futile. There are also high personal stakes: in committing to a voyage for enrichment one is also gambling one’s life based upon the political tenets of a home country that may have changed in the intervening years. The question of personal, professional and national loyalties become tested, as do the personal ethics of characters whose moral compass is marooned in time and place.

So, Mitchell’s novel also becomes a novel about what one believes and where one belongs. This may relate to the question of the role and status of women in society, for instance, the status of different races and the justifications of different races through the tenets of science, or the problems caused when tradition culture faces the encroaching beliefs of science and the thinking of the Western Enlightenment. It concerns the relationship of the individual with country and culture, also, and the vagaries of history.

There is a scene late in the novel in which a minor character tells Jacob of his past sentencing to the New South Wales penal colony and his later escape. He makes his way north and eventually is spotted by a ship flying an American flag. The American captain asks if he is an escaped convict. When he confirms he is, the Captain begins to quote the American Declaration of Independence verbatim. At this point in history, America has no love of Great Britain. Twomey’s backstory is an interesting aside in the novel, but it also highlights what drives most of the plot: while it is a story of adventure, conflict in Mitchell’s novel is driven not just by trade, profit and desire, but by religious, cultural and political rivalries that are reshaping the world.

Mitchell, as a stylist, is exemplary. His ability to set a scene brings the period and circumstances to life. He is able to progress scenes on several levels, seamlessly switching between action and thought, which is so important in this story that relies upon us understanding what his characters think of each other. And he is capable not only of dropping us into a scene of action and violence like the best writers of that genre, but also to evoke the ethereal beauty of his setting in language that is elevated to poetry.

This may make the novel sound burdensome to read, but it isn’t. The first third of the novel might be a stretch for some, since the intrigues of Dutch merchants over the reconciling of the company ledgers might sound somewhat tedious, but the latter two thirds of the novel often read like an adventure story, first with Uzaemon Ogawa’s decision to rescue Orito from the Mount Shiranui Shrine, and later with Jacob de Zoet’s stand against English imperialism. For those who have read Patrick O’Brian, this latter section is reminiscence of the Aubrey/Maturin novels, which were adapted for the screen by Peter Weir as Master and Commander, starring Russell Crowe. In the end, there just so happens to be a lot of derring-do, too.

Gulls fly through clouds of steam from laundries’ vats; over kites unthreading corpses of cats; over scholars glimpsing truth in fragile patterns; over bath-house adulterers; heartbroken slatterns; fishwives dismembering lobsters and crabs; their husbands gutting mackerel on slabs; woodcutters’ sons sharpening axes; candle-makers, rolling waxes; flint-eyed officials milking taxes; etiolated lacquerers; mottle-skinned dyers; imprecise soothsayers; unblinking liars; weavers of mats; cutters of rushes; ink-lipped calligraphers dipping brushes; booksellers ruined by unsold books; ladies-in-waiting; tasters; dressers; filching page-boys; runny-nosed cooks; sunless attic nooks where seamstresses prick calloused fingers; limping malingerers; swineherds; swindlers; lip-chewed debtors rich in excuses; heard-it-all creditors tightening nooses…

No one has commented yet. Be the first!