The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper

- Category:Non-Fiction

- Date Read:19 February 2020

- Pages:348 (416 including Notes, Bibliography and Index)

- Published:2019

- Prize:Baillie Gifford Prize for Non-Fiction 2019

The story of Jack the Ripper is one of those sensationalised moments in history that lends itself to all sorts of exploitation. There have been movies and novels, there is a vast number of books devoted to ‘ripperology’ and there have been many speculations about who the killer was, whether he was connected to the royal family, as well as what kind of mental state drove him to commit the murders of five women in Whitecapel in 1888. There was even the publication of a putative diary of Jack the Ripper in 1993, along with the discovery of a watch he purportedly owned, with an inscription of the victims’ initials scratched into its inner surface along with the claim ‘I am Jack’. The watch and the diary were supposed to have belonged to James Maybrick, a prosperous businessman who was himself murdered by his wife with arsenic. Maybrick’s visits to London coincided with the murders and the murders stopped after he died. Like any ripper suspect, he has his supporters and his naysayers. It’s all tantalising.

Hallie Rubenhold’s The Five is something different, however. As its title implies, Rubenhold’s book is about the five known victims of Jack the Ripper. It is an attempt to tell their stories; to return to them some identity and dignity. Rubenhold’s project is also contemporary. She is attempting to address attitudes to women’s sexuality and their place in society; to address how easy it is, still, to dehumanise and delegitimise women through pejorative labels.

Rubenhold’s book is not for the traditional ripperologist interested in Jack the Ripper’s story, looking for salacious details or new theories about the murderer’s identity. Her book is as much a social history as it is a series of five short biographies. Each of the five victims, Polly Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Kate Eddowes and Mary Jane Kelly have their stories recounted in as much detail as it is possible to draw from the limited material. As Rubenhold points out, much of the original documentary evidence from the coroners’ inquest for three of the women is now lost, and much of what is known of them derives from news reports which sensationalised the murders and were often contradictory in their details.

The details of the victims’ lives are necessarily sketchy, given the amount of information available about any individual from the period, especially if they were female and poor. But there is enough detail about each woman to get a sense of the trajectory of her life; of where she started, what she may have hoped for, along with key incidents which brought her low and made her susceptible to a predator. (Click on each woman’s name to the right to reveal some of the basic details covered by this book).

One of the most important questions Rubenhold seeks to address in her book is whether each of the victims were prostitutes. If your first thought about this is that it shouldn’t matter, then you have already gleaned Rubenhold’s position. But Rubenhold quotes this letter to The Times from a senior civil servant of the time, which is astonishing:

The horror and excitement caused by the murder of the four Whitechapel outcasts imply a universal belief that they had a right to life … If they had, then they had the further right to hire shelter from the bitterness of the English night. If they had no such right, then it was, on the whole, a good thing that they fell in with this unknown surgical genius. He, at all events, has made his contribution towards solving ‘the problem of clearing the East-end of its vicious inhabitants.’

Edward Fairfield, the letter’s author, has a middle-class understanding of the world and an attitude predicated on strict notions of right/wrong, good/bad. He has little understanding of poverty, and it is clear by his letter that homelessness is perceived almost as a wicked choice. Fairfield’s prejudice was common at the time of the murders. The homeless slept in their thousands throughout London and the situation of poor homeless women was seen as hand in glove with prostitution. Rubenhold seeks to examine the lives of each of the women, as well as the available testimony and other evidence, to test whether claims that Jack the Ripper was a murderer of prostitutes was true. As it turned out, one of the women was a prostitute, Mary Jane Kelly, but the assumption that the victims were prostitutes had been made since the first victim, Polly Nichols. The third victim, Elizabeth Stride, sometimes prostituted herself in the past, but there was no evidence she was prostituting herself in the period leading up to her murder. It’s an important point to establish: first, to understand the historical course of the investigation and the prejudices ranged against these women, but also to understand prejudice and misogyny in our own time. The ‘prostitution’ tag allowed the women’s lives to be dismissed, reduced them as human beings and to be held in contempt. Furthermore, it affected the investigation, since police believed they were hunting a prostitute killer, when in fact, Jack the Ripper’s five victims may all have died in their sleep, either in bed, like Mary Jane Kelly, or sleeping in the open.

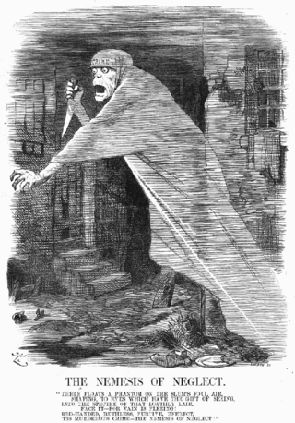

- THE NEMESIS OF NEGLECT.

- "There floats a phantom on the slum's foul air,

- Shaping, to eyes which have the gift of seeing,

- Into the Spectre of that loathly lair.

- Face it--for vain is fleeing!

- Red-handed, ruthless, furtive, unerect,

- 'Tis murderous Crime--the Nemesis of Neglect!"

But added to this is the ill-defined nature of prostitution. For the English police, they had no guidance until a ruling was made regarding Elizabeth Cass, a dressmaker erroneously arrested as a prostitute. The direction from the judge not to assume that any woman was a prostitute hardly had an impact on officers who, when filling out the occupation of Jack the Ripper’s victims for their victim reports, made an assumption and wrote ‘prostitute’. Rubenhold challenges the belief that the line between prostitution and some other circumstance was hard to define for a class of women whose only function was to support men, and to whom they were entirely dependent.

Rubenhold’s account is compelling and well-researched. She acknowledges the limitations of what is known about the women and clearly signals where her narrative becomes speculative. Yet any speculation is also based upon historical research into the similar circumstances of other women. The story of Mary Jane Kelly is exemplary of this approach. Little is known of Kelly’s origins except rumours and unfounded stories Kelly told about herself. One of the most formative moments in Kelly’s life – her luring to Paris to entrap her as a sex slave in a brothel – is sparse on detail. Instead, Rubenhold extrapolates possible scenarios from statistics and other anecdotal evidence: in 1884 at least 250 British women were abducted abroad, eventually to become sex slaves in foreign brothels. The story of Amelia Powell is indicative of the fate that might have awaited Kelly had she not extracted herself, somehow, in Paris. Transported to a brothel in Bordeaux, Amelia Powell found herself stripped of her clothes and was given silk dresses and other finery

for which she was indebted. Her only option, as far as she knew, was to pay the debt off by working in a brothel.

Rubenhold’s social history is not limited to the salacious. The picture she paints of London is a city at once in turmoil and celebration, defined by the thousands living in poverty and the militant agitation for workers’ rights, juxtaposed to the celebrations of Queen Elizabeth’s Golden Jubilee. It is a period in which the lives of women are precarious, dependant as they were on husbands or fathers. A death or a separation could lead to penury. The oppressive and degrading conditions of the London workhouses, where poor women might go for help, was sometimes the only option for some to survive, including Polly Nichols and Kate Eddowes. Added to their miseries, a factor that seems common between all these women, is the eventual dependence on alcohol to help them deal with their pain.

Rubenfold’s book is important because it not only gives these five women back their stories, as much as it is possible, but because it deconstructs the myth of Jack the Ripper. Dismissed as prostitutes, the five are uninteresting and faceless, while their unidentified killer assumes a mythic status imbued with Gothic power. Returned to the status of women whose backgrounds are diverse (Elizabeth Stride immigrated from Sweden, for instance), and whose circumstances are diverse, notwithstanding their eventual poverty which made them vulnerable, they remind us that this is a story of misogyny and hatred, and demonstrates the power assumed when another can be the means not only to interrupt the story of another, but to obliterate it, with social prejudice as an accomplice. This is an excellent social history which is politically relevant to feminist discussions of power today.

The Ripper's Five Victims

Click on each to reveal information about their lives

Father: Edward Walker - Blacksmith, possibly worked making type for Fleet Street printers.

Mother: Caroline Walker - Died of TB

Siblings: 2nd of three – Edward, Polly, Frederick

Education: Until 15. Could read and write

Marital Status: Married to William Nichols 1863

Children: Six children

Hardship: Husband began relationship with Rosetta Walls (employed to help Polly after pregnancy). This resulted in Polly’s long-term homelessness and reliance on the Government Workhouse system. Dependence on alcohol. Lost her children to husband and Rosetta

Means of support: Workhouses, Begging, Domestic Service

Evidence she was a prostitute: None. Evidence strongly suggests she never was.

Murdered: 31 August 1888

Father: George Smith, Member of Queen’s Life Guard; Valet to Commanding Officers; House Servant

Mother: Ruth Chapman

Siblings: 1st of 8 – Annie Eliza (born out of wedlock), George William Thomas* (born after parents’ marriage was officially backdated prior to Annie’s birth), Emily Latia, Eli**, Miriam**, William** - Born after Scarlet Fever and Typhus outbreak - Georgina, Miriam Ruth

- (Four siblings died in a 3-week period)

- * Died of Typhus

- ** Died Scarlet fever

Education: Education compulsory for regimental children. Received education through Regimental School.

Marital Status: Married to John Chapman, coachman, head coachman. De facto with Jack Sievey after separation from husband, later with Edward Stanley

Children: Emily Ruth (died age 12 – meningitis), Annie Georgina

Hardships: Father’s suicide (cut his own throat) led to mother losing husband’s army pension. Annie an alcoholic as was probably her father. Separated from husband to save his job after he was warned about her drunkenness. Husband’s payments to her stopped when he died at age 45. Often slept rough because lodging money was spent on alcohol.

Means of support: Domestic Service, peddling, crochet work, selling matches and flowers

Evidence she was a prostitute: None

Murdered: 8 September 1888

Family Background: Swedish. Elizabeth emigrated to England in 1866

Father: Gustaf Ericsson, Farmer

Mother: Beata Ericsson

Siblings: 2nd of – Anna Christina, Elisabeth

Education: Minimal. Mostly religious

Marital Status: Married John Stride, a carpenter who attempts to run coffee houses. Cut from his father’s will, he is forced to sell second coffee house. De facto relationship with Michael Kidney after John Stride’s death

Children: Stillborn girl

Hardships: Became pregnant out of wedlock (illegal in Sweden) and subjected to regular examinations by police. Contracted syphilis. Mysterious scandal forced her from domestic service in London. Arrested once for soliciting, arrested several times for drunk and disorderly. Suffered late stages of syphilis.

Means of support: Domestic Service, prostitution (Sweden), Maidservant to British family returning to London, Coffee Houses with husband, prostitution (London), charwoman, con artist.

Evidence she was a prostitute: Became a prostitute in Sweden after she appeared on police register for pregnancy. Arrested once in London for soliciting, but no evidence she returned to the trade after that.

Murdered: 30 September 1888

Father: George Eddowes, Tin worker, dies of TB

Mother: Catherine Eddowes, dies of TB at 42

Siblings: 6th of 12 – Alfred (Mentally disabled – epileptic fits), Harriet, Emma, Eliza, Elizabeth, Catherine, Thomas, George, John, Sarah Ann, Mary, Willian

Education: Attended Dowgate School. Taught reading, writing, arithmetic, the Boble, music and needlework. Well-educated and deemed smart

Marital Status: De facto relationship with Thomas Conway, former British soldier, now chapbook seller and pedlar. Later has de facto relationship with John Kelly (who also drank) after split with Conway.

Children: Catherine, Thomas Lawrence, Harriet, Frederick (died in infancy)

Hardships: Father forced to bring family to London after arrest over industrial agitation left him without work. Tin-working job in London inadequate for his large family. Employer dissolved when Kate was 14. Father died of TB when Kate was 15. Forced into workhouse when about to give birth due to lack of permanent home. Kate became dependent on alcohol. Arrested twice drunk and disorderly. Beaten badly by Thomas Conway. Estranged from her sisters over her drinking problems

Means of support: Tin Scourer. Polisher. Chapbook seller and pedlar. Begger.

Evidence she was a prostitute: None. The judge at her inquest assumed prostitution after John Kelly said he didn’t want to see her walk about the streets at night

. He meant she would often be forced to walk about, having been moved on by police when she couldn’t afford the money for lodging. Kelly was attempting to avoid the fact that he had used money to obtain lodging for himself on the night of her murder, while she had none.

Murdered: 30 September 1888. She was released at 1am from a gaol cell still drunk after she was arrested for being drunk and disorderly earlier in the evening. She had nowhere to go.

Father: Unknown

Mother: Unknown

Siblings: Unknown

Education: Presumed to be well-educated, possibly from a middle-class family.

Marital Status: Claims to have been married at 16 to a miner named Davies or Davis – uncertain. Joseph Fleming, lover. Joseph Barnet, lover who spoke at her inquest.

Children: May have had a child in 1883. No evidence of its existence.

Hardships: May have been disowned or sent away by family after sex before marriage. Escaped abduction and exploitation in a brothel after a trip to Paris, but lost trunk with expensive dresses. But may have had to abandon more lucrative prostitution and live in lower-class neighbourhood to avoid retribution by her would-be captors. Became alcohol dependent after this experience.

Means of support: Prostitute for wealthy clients, sometimes attending dinner events for gentlemen. Later worked in lower class neighbourhoods as prostitute. Gave up prostitution when she began relationship with Joseph Barnet.

Evidence she was a prostitute: She was.

Murdered: 8 November 1888, while sleeping in her bed. While she had worked as a prostitute, she was not soliciting when she was murdered. She was asleep.

No one has commented yet. Be the first!