- Category:Historical Fiction

- Date Read:2 October 2018

- Pages:636

- Published:2000

- Prize:Pulitzer Prize for Fiction 2001

Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay is a fictional account of comic books during the ‘Golden Age’ of comics. The story centres upon comic book creators Josef Kavalier and Sammy Clay, beginning in the late 1930s and ending with the hearings of the United States Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, otherwise known as the Comic Book Hearings of 1954. Chabon’s novel does not read like a Boys’ Own Adventure, despite the promise of the title, although there are various scenes in the book which are gripping and adventurous, including Josef’s (Joe’s) escape from Prague to America sharing a sarcophagus with a Jewish Golem, to his period in Antarctica as a radioman listening to Nazi U-Boat signals, where he even mounts a daring if somewhat pointless attack on a lone German geologist in another Antarctic station. The novel, while long, is varied in scene, with chapters often reading like a self-contained instalment of a long work, much like the serialised stories of comic books. In short, the novel is pure entertainment, even if it has things to say about popular culture, sexuality and fatherhood, too.

(Actually, there’s that scene in which Joe leaps from the Empire State Building, and another where he foils a Nazi bomb plot while performing a magic show, so maybe there is that element of adventure running through the plot, just enough to help us see the point: that the key characters Joe and Sammy create in their comics, especially the Escapist, based on Joe’s hero, Harry Houdini and his mentor Bernard Kornblum, reflect their own lives and times.)

The plot is simple enough. Joe, having escaped Prague, is anxious to save money to enable his family to also escape Europe before things get too bad for Jews. He is a prodigiously talented artist, and when he turns up at his cousin’s house to live, Sammy sees his potential. With the kind of audacity that only young men possess, they strike a comic book deal with Sheldon Anapol and Jack Ashkenazy, merchandisers of novelty items and owners of Racy Publications, which produces low quality magazines to flog their low-quality merchandise. They see the boys’ potential to help them counter the sudden popularity of Superman. The comics are a success. They all earn huge amounts of money. The war breaks out. Joe becomes embroiled in fighting Germans on the streets of New York, Sammy faces an uncertain personal future as he begins to struggle with his sexuality, and Joe focusses all of his financial efforts upon getting his young cousin, Thomas, on a ship to America, and preparing the way for the rest of his family.

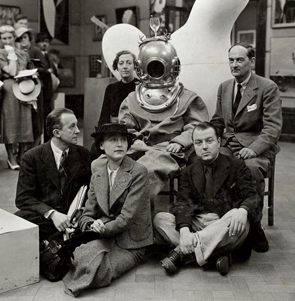

Of course, the story progresses beyond this, with nothing happening quite as expected. But apart from the plot, which is engrossing in itself, the novel is also fascinating in the way it meshes its fictional story with real events, or twists famous moments now vague in the memory of popular culture into entertaining scenes. For instance, Sammy and Joe make the acquaintance of Longman Harkoo and his daughter, Rosa Saks, a girl Joe had only glimpsed naked years before when he broke into an artist’s studio to procure a place to work, at a party being held by Harkoo. Harkoo has enough social clout that he is able to attract the crème of New York’s Surrealist movement, with Salvador Dali in attendance, dressed in a deep-sea diving outfit. The scene recalls a real incident a few years before the novel’s party in which Salvador Dali attempted to deliver a speech from within a deep-sea diving outfit. Something went wrong with his air and he almost suffocated until the helmet was prised from his head with a billiard cue. Chabon changes the time and place, but the scene is no less dramatic, and gives Joe the opportunity to use his escape skills to free the helmet from Dali.

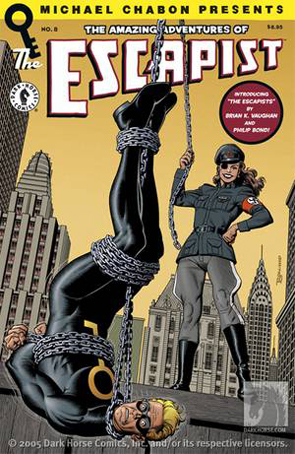

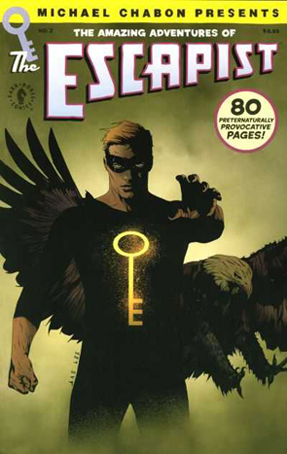

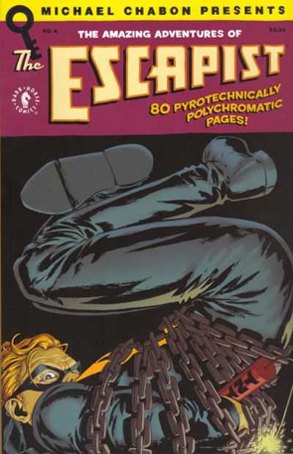

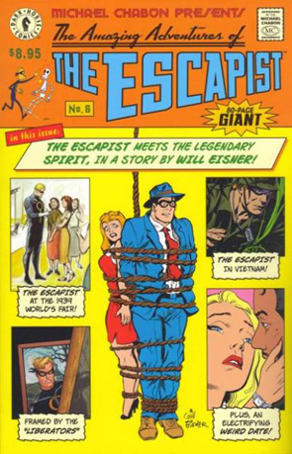

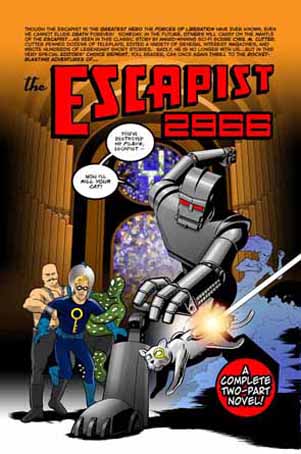

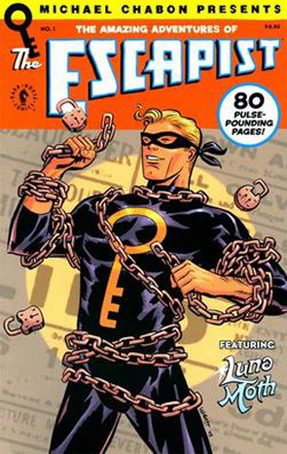

The idea of escape pervades the novel. Joe not only effects an escape from death for Dali, but he also escapes Europe. Sammy and Joe’s main comic book protagonist is the Escapist, a man versed in the art of escape, much like Harry Houdini, who bears the Golden Key which miraculously heals his lame leg while ever he bears it (Sammy has a lame leg from childhood polio), and uses his power and talents to free others from tyranny. The first cover Joe produces for Anapol features a picture of the Escapist punching Adolf Hitler. Anapol doesn’t want to use the cover – he doesn’t want trouble – since America is not at war with Germany at the time. But Joe’s cover merely reflects the tendency of real comics of the time to have superheroes fighting Nazis and, if possible, punching Hitler. Captain America did it. So did Superman.

The novel explores the idea of escape on other levels. For instance, life’s entrapments can be of a more existential prison, like the prison of living a false life, such as Sammy’s need to hide his homosexuality, or the burden of secrets. And the idea of escape – or ‘escapism’ – bears the weight of conservative opprobrium, since the escapism offered by comics is problematised because of their depictions of violence and their perceived latent homosexuality.

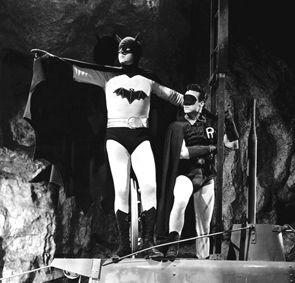

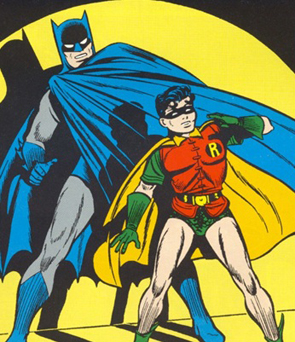

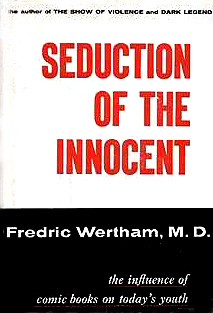

This is particularly evident in Chabon’s use of the historic controversy surrounding comics during this period. Dr Frederic Wertham, author of Seduction of the Innocent, was a German-American psychiatrist who argued that comics were depraved and potentially hazardous for young people to read. The violence of superhero and horror comics, the sexually explicit costumes of characters and the relationships of characters like Bruce Wayne and his ward, Dick Grayson, which he argued were implicitly homosexual, were identified by Wertham as factors contributing to juvenile delinquency, the subject of the senate subcommittee of 1954. The Comic Book Hearing actually coincided with the McCarthy hearings, which focussed on the threat of communism, but also heard allegations of homosexuality, too. This was an era in which the mere suggestion of being a communist (or homosexual) could ruin lives and careers.

Chabon threads the threat of the Comic Book Hearing into the second half of his novel, and it is through this seemingly minor strand in the plot that we see his skill as a writer and the intent of his book. His metaphor of the Jewish Golem – an anthropomorphised creature born from the earth and a magic word – is, from the start, a metaphor of escape. Joe escapes Europe in a box with a Golem. He also creates a comic book of thousands of pages based on the Golem and reflects:

. . . that he and Sammy had filled over the past dozen years: boxes brimming with the raw materials, the bits of rubbish from which they had, each in his own way, attempted to fashion their various golems. In literature and in folk law, the significance and the fascination of golems - … lay in their soullessness, in their tireless inhuman strength, in their metaphorical association with overweening human ambition, and in the frightening ease with which they passed beyond the control of their horrified and admiring creators. But it seemed to Joe that none of these – Faustian hubris, least of all – were among the true reasons that impelled men, time after time, to hazard the making of golems. The shaping of a golem, to him, was a gesture of hope, offered against hope, in a time of desperation. It was the expression of a yearning that a few magic words and an artful hand might produce something – one poor, dumb, powerful thing – exempt from the crushing strictures, from the ills, cruelties, and inevitable failures of the greater Creator. It was the voicing of a vain wish, when you got down to it, to escape.

Of course, Wertham’s argument was based on a belief that through the correlation of facts one could determine a cause: if violence existed in society, for instance, and comic books were being read, then one had identified the culprit. But as Chabon’s novel seems to demonstrate by focussing on the extraordinary lives of its protagonists and the times in which they live, art reflects life. The Escapist is an amalgam of Harry Houdin’s fame, of Joe’s interest in magic and the art of escape, of the entrapped lives of many in Europe, especially Jews, and of Sammy’s lame leg and prodigious imagination. If the Escapist (or Captain America) punches Hitler in the face, then there was a prior violence that art is reflecting, and a need to express this desire as a panacea to helplessness. Comic books, like the golem, represent not just escapism, but hope.

Michael Chabon’s novel may be a long read, but it doesn’t feel long. The variety of incidents, the use of subplot that connects the imaginary and real, the appearances of real people – I forgot to mention, Stan Lee makes a few appearances, just like in the Marvel movies – and the respect Chabon pays to this derided medium (he acknowledges comics as worthy of the term ‘art’ and makes their derision seem perplexing), along with the sheer entertainment value of this book, makes it one worth reading.

Dr Frederic Wertham

The Escapist

No one has commented yet. Be the first!