ISBN:9780571368686

- Category:Fiction (General)

- Date Read:29 August 2022

- Year Published:2021

- Pages:110

- Prize:Orwell Prize for Political Fiction 2022

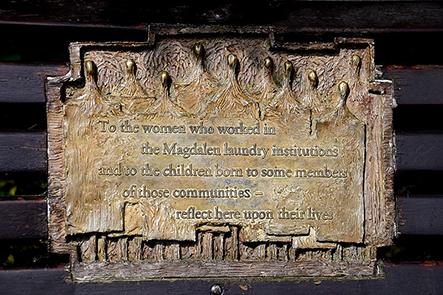

Claire Keegan’s Small Things like These became the shortest book ever nominated for the Booker Prize when it was Longlisted in July 2022. This slight novella – only 110 pages – is dedicated to “the women and children who suffered time in Ireland’s mother and baby homes and Magdalen laundries” and uses an excerpt from Ireland’s 1916 Proclamation of the Irish Republic as an epigraph, which reads in part, “The Republic guarantees religious and civil liberty, equal rights and equal opportunities to all its citizens…” Taken together, these suggest a work of overt socio-political insight. Therefore, it seemed natural to me to read a little bit about Ireland’s Magdalen laundries before starting Keegan’s book.

The Magdalen laundries were run by the Catholic Church. Established in the late 18th century, they were well established institutions throughout the 19th and well into the 20th century. Keegan notes in an afterword, that the last Magdalen laundry was closed as late as 1996. The laundries were meant to rehabilitate ‘fallen women’, which in the early period meant prostitutes, but later came to mean women who had children out of wedlock or were deemed immoral or even mentally unfit in a variety of ways. The women worked in the laundries which earned money for the Church, which helped to pay for their upkeep. Part of the moral issue with the laundries, as was highlighted late into their operation, was that many of the women became institutionalised and were never reformed, as was the purported mission of the laundries, and since the women worked for no pay, their service was tantamount to a form of slavery.

Given that Keegan chose to bookend her story – her dedication and afterword – with the history of the Magdalen laundries, I anticipated a book that delved into the history of these institutions: something in the vein of Colson Whitehead’s The Nickel Boys, a novel which documented the abuse suffered by children over a long period in a fictionalised representation of the Dozier School for Boys in Florida between 1900 and 2011. The comparison seems particularly apt since, like the Dozier School for Boys, one of the laundries, run by the Sisters of Our Lady of Charity in High Park, Drumcondra, was found in 1993 to have 133 unmarked graves on its property. There was no death certificate for 58 of the bodies found. There is, however, no mention of anything like this in Keegan’s book.

In fact, Small Things like These is not the book I was anticipating. It is not overtly political, except that it raises the subject of the laundries at all. It is not an unmasking of the institutions run by the Catholic Church throughout this long period, nor does it address the social scope of the treatment of these women and their children except in the few specific instances in the plot. It does portray the impact of being institutionalised in one of these laundries, and suggests the power by which the Church avoids criticism. Yet the real focus of Small Things like These is upon the moral question of personal action rather than the wider social questions the narrative essentially raises.

Imagine, if you can, a Dickensian tale of late-twentieth-century Ireland, of poverty and the economic uncertainties of the period, which loosely parodies Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. There are no Christmas ghosts, nor is there an exactly equivalent Scrooge character whose reprehensible moral compass needs turning. But the parallels are there, sometimes even in little details that are of no real import to the story, like the plight of the barber’s son who has been stricken with a rare type of cancer, recalling the illness of Tiny Tim in Dickens’s novel.

It is Christmas 1985 in the town of New Ross, Ireland, and Bill Furlong, a coal and timber merchant, is anticipating a brief shutdown and Christmas with his family. Bill is an uncomplicatedly good man who cares for his wife – he only has a brief thought about what it might be like to be married to his neighbour – and five daughters. Bill and Eileen understand that while they may not be able to afford new windows to keep the cold draughts from their home, they are nevertheless lucky. Even if their Christmas will not be lavish, around them they see poverty, businesses closing and people emigrating, hoping for a better life. Their two eldest daughters attend St Margaret’s, run by the same convent that runs the laundry. And they are not in debt. Their immediate problem is what to buy their daughters for Christmas.

There are no simple parallels or equivalences in this story with Dickens’s novel, but Keegan takes care to plant enough clues for us to see the similarities. Bill remembers a Christmas when he was younger: disappointed not to receive the jigsaw he asked for, he instead received an old copy of A Christmas Carol. Now that he is older the only thing he can think to ask for Christmas is a copy of David Copperfield, since he never got around to reading it. Keegan’s story rings with the sentimentality of Dickens, particularly in the story’s opening chapters, and Bill’s thinking is coloured by concerns about the routine struggles to make ends meet, and an existential question about the purpose of his life:

Lately, he had begun to wonder what mattered, apart from Eileen and the girls. He was touching forty but didn’t feel himself to be getting anywhere or making any kind of headway and could not but sometimes wonder what the days were for.

This may sound a little more like Bob Cratchit than Ebenezer Scrooge, but for the purposes of the plot, Bill Furlong represents elements of both. If he is not the working poor, then he represents the tenuous existence that might change the fortunes of any man and his family for the worse. These changeable fortunes are alluded to in a conversation between Bill and Mrs Kehoe: “You’ve reared a fine family of girls – and you know there’s nothing only a wall separating that place from St Margaret’s.” “That place” is the laundry. The idea of a “wall” serves to remind Bill that while his daughters are lucky, many girls are not. He understands that his mother may have been one of those girls, and in turn he may have been one of those children, were they not saved by the kindness of Mrs Wilson. Mrs Kehoe, in telling him this, also intends to point out the dangers of acting morally against the interests of the Church.

It is the question of a moral decision which paradoxically makes Bill something of a Scrooge character. Bill does not act heartlessly against others, but for Bill, this is not enough. The point of Dickens’s Scrooge is his transformation from a selfish to a selfless man. To this end, Keegan’s novel is structured to reflect the past, present and future as guides in Bill’s moral journey.

Bill’s past is defined by the example of Mrs Wilson. Mrs Wilson, a selfless Protestant widow, allowed Bill’s mother to stay at her place after Bill’s father, whose identity remains a mystery to Bill, is reported to have left. Mrs Wilson’s religion might be read as something of a dig against the Catholic Church which ran the laundries. But Keegan never digs the knife in as far as she might. Bill’s wife defends the actions of the Church, suggesting that Mrs Wilson’s enlightened treatment of Bill’s mother was a matter of privilege that is not available to others: “Sitting out in that big house with her pension and a farm of land and your mother and Ned working under her. Was she not one of the few women on this earth who could do as she pleased?”

Bill’s present is informed by the plight of a young girl he finds in a coal shed in the convent whilst delivering coal. The girl has spent so long there she has been forced to soil herself. But she has done this despite the cold of winter and the humiliation, so long as she escapes the control of the Mother Superior and her convent for a while. Bill is disturbed by the self-righteous, unpitying reaction of the Mother Superior, and the girl’s desperate pleading to him for help, even if it is only to allow her a chance to drown herself in the river.

Finally, Bill’s future is one he envisages, himself, filled with the purpose of helping others, regardless of the challenges he might suffer as a result.

Keegan has chosen to structure her novel around Dickens’s Christmas story, which transforms its potential into a story of personal moral redemption, and rather less focussed on the social impacts of Church policy, not to mention the implications of poverty and the obligations of the State regarding its Social Contract, as suggested by the novel’s epigraph. I think this makes it a lesser novel than it might otherwise have been, because its denouement simplifies complex social, political and religious questions into an act of moral metonymy: by which I mean that if Bill Furlong’s decisions and actions are to mean anything, then they stand as an example for the rest of us. In short, it ends up feeling like an allegorical journey hoping to address social and historical wrongs.

Part of the problem of the denouement is that it does not allow its protagonist to separate his values from the institutional beliefs of the Catholic Church. An uncharitable estimation of the history of the matter would have it that the problems of the laundries were instigated by moral codes defined by religious beliefs, as well as pecuniary concerns. Yet Bill Furlong’s epiphany remains within the ideological constraints that underpin the raison d'être of those institutions. While the novel may portray the laundries in a bad light – the scene with the Mother Superior and another featuring Mrs Kehoe’s warning against Bill taking action are brilliantly executed – it does not provide a critical position against their very tenets. Bill’s idea is not to challenge the system but to become a more perfect avatar of its religious creed:

Was it possible to carry on along through all the years, the decades, through an entire life, without once being brave enough to go against what was there and yet call yourself a Christian, and face yourself in the mirror?

In the end, we are encouraged to admire Bill rather than abhor the system: the sacrifice is Bill’s sacrifice, the insight and moral elevation also Bill’s. It is Bill’s religious inner turmoil – a spiritual and moral suffering – with which we must identify, while the story of those who suffer under the system seems of secondary import to the purposes of the narrative; merely a vehicle for Bill’s religious illumination. I think Keegan’s afterword shows a genuine commitment and concern for the fate of thousands of women and children subjected to the Magdalen laundry system, but the novel, in the end, feels like it is redefining a religious creed to separate it from a terrible past. I can imagine that some readers will find this uplifting, but I found the thinking behind it alienating.

No one has commented yet. Be the first!