- Category:Fiction (general)

- Date Read:25 March 2019

- Pages:181

- Published:1979

- Prize:Booker Prize 1979

I read Penelope Fitzgerald’s The Book Shop last year and was impressed. The impression that book made on me and our website’s ongoing project to read all the Man Booker Prize winners led me to Offshore. Offshore won the Booker in 1979.

How?

That was the overwhelming feeling I had when I finished this novel. How was this book selected?

Offshore is a slight novel at only 180 well-spaced pages and it has the feel of a book that still needs development. The book was interesting enough, but its disparate elements seem unresolved and therefore lack a sense of significance. The ending, if I can give away a vague hint here, involves the return of a minor character and an incident that seems like the beginning of a whole new story arc. Left unresolved, I was hard pressed to understand its why it ended as it did.

Offshore tells the story of Londoners who are mostly down on their luck and live on old houseboats in the Thames. There’s Maurice, a male prostitute who allows Harry to hide his illegal contraband in his hold. There’s Willis whose prospects are diminishing and hopes to sell his badly leaking boat in order to move in with his sister. There is Richard Blake and his wife, both affluent enough to buy a real house. But Richard insists on living life on the river, which is driving a wedge into his marriage with Laura. There’s Woodie, an artist with a deft hand, but his works aren’t fetching the prices they once did. And then there’s Nenna James and her two daughters, Tilda, only six years old, and Martha, now twelve. Nenna’s husband, Edward, took a 15-month contract to work in Panama. He was meant to be saving money but he hasn’t and Nenna, knowing him, knew he wouldn’t. Now, having returned to England, Edward is living with an old school mate and Nenna wants him back. She plagues herself with endless imagined cross-examinations in an imagined court case that puts her own actions under scrutiny.

These are ingredients for a potentially great novel, especially had Fitzgerald approached her subject matter with the same sophistication and finesse as The Book Shop. But there are bum notes and unexploited points throughout. The two daughters, for instance, seem strangely characterised. They speak with all the sophistication of an adult, even 6-year-old Tilda. For instance, Martha shows more erudition than Mr Stephen, the proprietor of the Bourgeois Gentilhomme, an antique store, to whom she intends to sell valuable tiles she has found in the Thames mud. She knows their value – they are, after all, examples of William de Morgan’s late work she tells him. When Mr Stephen demurs – the lettering on the reverse is wrong for a Williams he tells her – Martha points out that Williams finished his career in Sands End, in Fulham. Mr Stephen is left defeated. Then there are important plot points which are just abandoned, like Father Watson who turns up at the beginning of the novel to pressure Nenna into making her daughters attend school. One anticipates a major source of conflict being established, but Father Watson isn’t heard from again until later in the novel when his potential is reduced; he simply becomes the means by which to offload some unexpected kittens. There’s even the son of a German count who visits them for a day, the sixteen-year-old Heinrich von Furstenfeld, the son of a friend of Nenna’s sister (who seems to play no other real role than to make this unlikely connection for Nenna). Heinrich shows Martha the potential of another life and coldly offers a barren flirtation. But as a subplot, it is hard to know whether to understand this in the light of Nenna’s marriage or her own barren flirtation with Richard. Which is another subject again. We glean that Richard and Nenna have had a sexual encounter on the afternoon they realise they both have possibly lost their partners. In a short reverie, Richard recalls his encounter with Nenna the previous day, formerly unnarrated in the novel: It was rather a coincidence that she was wearing a dark blue guernsey exactly like Laura’s, with a neck which necessitated the same blindfold struggle to get it off

But what of this affair or its attendant flirtations? Richard goes and gets himself concussed in an unlikely and somewhat irrelevant plot point, then Laura returns to Richard while Nenna’s anger at Edward begins to set. Yet Nenna has accidentally left her purse and valuables with Edward when she went to visit him. Surely, they will be driven back together? As it turns out, Edward has enough decency to try to return the purse but circumstances sidestep him on a somewhat perilous and irrelevant adventure.

And this is where the book needed to shine. Nenna’s predicament – a woman increasingly in the single-parents camp with two girls, under pressure from authorities to attend school, and driven to use the last of her money to purchase a second-rate home on the river – is real. One senses the reality of the setting, for a start. Fitzgerald drew on her experiences of living on the Thames for a few years to write this novel. Yet the heart of the story should be Nenna’s marriage, and the best scene in the book, in my opinion, is when Nenna finally has the nerve to visit Edward to try to persuade him home. Fitzgerald is great at small details. Nenna’s fear, for instance, that Edward will not return home, is expressed as a small hope she nurtures – a last hope – which she wishes to cherish as long as possible. Which is why she waits so long to visit him. And when she stands in his small rented room, looking disapprovingly at his single bed, her observation speaks volumes of her desire to embrace her husband and their marriage once again. Her antipathy towards Gordon Hodge and his mother, Edward’s landlord, is brilliant. Having dismissed Gordon, who insisted on staying to hear their personal business, with a sharp Get Out!

, Gordon goes down stairs to thump away aggressively at the piano. Gordon is something of a pianist

Mrs Hodge tells Nenna placatingly. No, he isn’t,

Nenna asserts.

Yet the promise of this scene, I feel, is lost. I am not suggesting from this there had to be a happy ending or a sad ending to make the book better. I thought the book needed an ending that made sense of the situation the characters found themselves in and gave their stories some significance. When I finally saw the movie adaptation of The Book Shop I was disappointed by the ending being changed from the book. The movie was good, but the revised ending robbed the story of the significance of Florence Green’s life and her struggles to keep her shop in the face of Machiavellian forces. But the ending of Offshore seems random and chaotic and the novel’s parts poorly resolved.

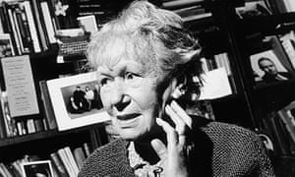

So, how can I be so critical of this book which won the Booker Prize, I kept thinking to myself as I sat to write this review. After all, its prose is elegant, the setting is convincing, the characters are well drawn and there is a lot of potential here. But I felt the book needed further development. Was I really just missing something the Booker judges saw? So, I did a quick Google search and found a Guardian article which addressed some of the same concerns I had. The full article can be found here. But I want to end this review by doing something I would normally avoid, by quoting two paragraphs from that article.

On the decision to award Offshore the Booker, the article states:

Hilary Spurling, one of those judges, noted that the decision had surprised them as much as everyone else: "We'd spent the entire afternoon at loggerheads, settling at the last minute by a single vote for William Golding's Darkness Visible, by which time the atmosphere had grown so heated that I said I'd sooner resign than have any part in a panel that picked a minor Golding over a major imaginative breakthrough by Naipaul. So we compromised by giving the prize to everybody's second choice."

On the impact of the win on Penelope Fitzgerald, the article states:

Hillary Spurling also said the widespread incredulity that greeted this unexpected triumph caused Fitzgerald “pain . . . and humiliation ever after”. The author was probably all too aware that this wasn't the best book on the shortlist – or even her best. It's perhaps also the reason her later, far better historical novels didn't even get a look-in for the prize. Injustice all round.

I think Spurling was generous in calling Offshore their second choice. I wondered at it being shortlisted. Yet The Book Shop had deservedly been shortlisted the year before but was beaten by Iris Murdoch’s The Sea, The Sea. I liked Murdoch’s novel, but I thought Fitzgerald’s book should have won that year. That’s the way it goes.

the widespread incredulity that greeted [Fitzgerald's winning the Booker Prize] ... caused Fitzgerald 'pain … and humiliation ever after'

Quoted from Sam Jordison's Guardian article, 13 March 2009 (https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2009/mar/13/booker-prize-fitzgerald-offshore)

No one has commented yet. Be the first!