- Category:Biography

- Date Read:19 January 2018

- Pages:310

- Published:2017

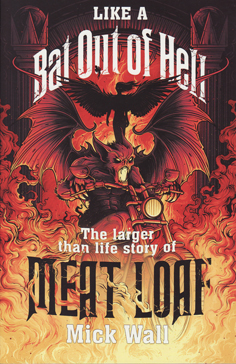

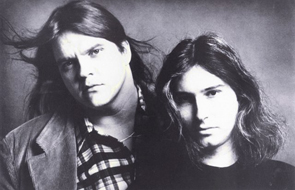

Full disclosure: I have been a fan of this music since I first heard it in 1981. That’s deliberately vague. Mick Wall’s book Like a Bat Out of Hell is a biography about Meatloaf, but his career is so inextricably entwined with Jim Steinman, his songwriter, that Steinman features a great deal in this book, also. In fact, he bookends it. The opening and closing of the book focus on Steinman. He even gets the biographical treatment, with his personal background and education receiving its own chapter, just as Meat Loaf’s does. And when I say this music

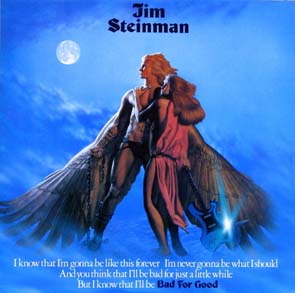

, I mean that I have been a fan of Steinman’s songs over that time, whether they have been performed by Meatloaf, Steinman, Bonnie Tyler, Air Supply or Celine Dion. They are Gothic, overblown romances, cinematic, funny, complex and operatic. They are so many other things, also, and when I was younger they rewarded close listening and analysis. As for Meatloaf, his later career was not of much interest to me. His Midnight at the Lost and Found album was an abysmally ordinary record, Bat Attitude tried to imitate Steinman’s style, but didn’t get there, Bat Out of Hell II was better with Steinman once again writing, but after Blind Before I Stop I never bothered with Meatloaf’s albums, except for Bat Out of Hell II even when they were penned by Steinman. His voice had long ago faded after the torturing year-long tour he undertook to promote Bat Out Of Hell in the late seventies and the subsequent years of vocal abuse while on tour.

Nevertheless, this book was hard to resist.

The last book I read on Meatloaf and Steinman was Meatloaf, Jim Steinman and the Phenomenology of Excess by Sandy Robertson. It was a kind of fanzine book published in 1981 when Steinman and Meatloaf were both releasing records to try to follow up their success they had with Bat Out of Hell. It fairly gushed over Steinman’s work – even then the writing about the music tended to focus on Steinman’s creative genius – with little critical insight into the music. It gave a somewhat less detailed account of the years up to that point that is now recalled in Wall’s book. Naturally, Wall’s book follows their careers beyond the disappointing reception of Bad for Good by Steinman and Meatloaf’s second studio album, Dead Ringer, also penned by Steinman. But my first impression of the book was that it was not much more insightful than Robertson’s. It was an account written by a fan and it tries to engage fans through its language.

The language of Like a Bat Out of Hell is fairly colloquial. Take, for example, this, from chapter 7 of the book, which is where I just opened it:

Hair in New York was a fucking disaster. The producers had gone hog crazy and fired half of the existing cast, so everyone who turned up from the Detroit production was stepping into dead men’s shoes. Then there was the whole living-for-the-city New York vibe to deal with . . .

From the same page:

It didn’t hurt, though, when Papp’s people offered him a job as part of their Shakespeare in the park project. Meat knew he was a singer, not a proper thesp, but hey, he needed the dough.

The whole book is written in this colloquial, chatty style. I have no problem with colloquialism, swearing or any other language Wall uses. What struck me, however, was that it felt a little manipulative, at times, since the language suggests an implied reader, and I am nothing like Wall’s assumed audience. Wall uses language to buddy up to the reader, and my first impression was that Wall was inviting the story to be read at the level of an uncritical fan, since the language is that of a fan, and I wasn’t sure that I wanted to read a sycophantic fan account. At the same time, I was also aware that Wall’s tone achieved something a biography should: it helped to characterise its subject. I’ve seen many videos of Meatloaf speaking and performing and I’ve seen him live three times. The last time was in a club in the Western Suburbs of Sydney, just before he had the incredible success with his second Bat Out of Hell album and the hit ‘I’d Do Anything for Love’. (An aside: during that show Meat Loaf promoted the album and heavily emphasised his renewed affiliation with Steinman, and the fact that Steinman was contributing all the album’s songs. It reinforced for me how much of his success was derived from Steinman). As I read it occurred to me that the tone of the book approximates the language and tone used by Meatloaf and captures some of his persona. I eventually managed to settle into reading the book and not be bothered so much by the style, although who can forgive a line like this: “The little big family sprung apart like dark matter in a black hole”. Is that how dark matter and black holes work? I don’t know. It’s a fairly shaky metaphor and just terrible writing.

The other thing I wondered as I began was how it would treat the estrangement between Meat Loaf and Steinman that lasted a decade and the law suits that continued beyond Bat Out Of Hell II. Meat Loaf declared bankruptcy in the years before Bat Out Of Hell II. His career suffered. He produced mediocre albums. Then he and Steinman worked together again and Meatloaf had his second huge success. I wondered how Steinman would be portrayed by the author – as the villain, perhaps? – and how Wall would handle the thorny question of Meatloaf’s successes and Steinman’s contribution. For a Steinman fan, the answer seems obvious, but even a Steinman fan cannot deny the importance of Meatloaf’s incredible vocal contribution to Steinman’s baroque compositions.

However, I thought Wall’s account was fairly balanced. Wall criticises and praises both men throughout the book and calls attention to their inconsistent and conflicting accounts of their collaborations and feuds over the years. For instance, he criticises Steinman for his voice, which he describes as “good but not great”, and gives credence to this assessment by revealing that that Rory Dodd sang much of the most vocally demanding sections of ‘Lost Boys and Golden Girls’ and ‘Surf’s Up’, uncredited, a fact I never knew before. At the same time, Wall reveals that Meatloaf’s failure to sing the Bad for Good album was not just due to the problems with his voice. He had rejected the album as not good enough and too similar to Bat Out of Hell, showing poor judgment, missing an opportunity, and making the marketing of the albums a confused affair, since Meat Loaf’s voice was good enough to produce Dead Ringer, anyway, and they were released close together. He would eventually record many of the Bad For Good songs on later albums.

Naturally, Wall is a fan of the music and the duo, so he is also lavish with his praise of both men: for Meat Loaf’s extraordinary voice, and Steinman’s vision and writing talent. Despite this, he avoids the gushing fandom of Robertson’s early account. I think his documentation of the later years of Meat Loaf’s career, and Steinman’s dwindling involvement, lifted this book. Not only does he recount the problems the pair faced, but the failing creative forces of both men as they have grown older, ending with their final collaboration Braver Than We Are of which he says, it wasn’t a great record. It wasn’t even a particularly good one

and described Meat Loaf’s voice as “ravaged by the years, it was old and broken”.

What also adds to the value of this book is that Wall interviewed both men throughout their careers and kept detailed transcripts of all the recordings. He uses this effectively in the final chapters as he tries to get to the heart of why Steinman was not involved in Bat Out Of Hell III

. It’s a question that goes to the heart of the relationship between the two men. Wall quotes extensively from interviews between both men, giving each a full chapter in the book to discuss the issue, and considers the impact of Steinman’s health – having suffered a heart attack and strokes – as well as the ongoing legal battles between the two. Wall’s approach is more journalistic in the second half of the book, using the interviews to show inconsistencies in the accounts about the production of the album, as well as delving beyond the account either man is initially willing to give, to consider the legal problems that beset the third Bat album.

Wall’s book will also be important to future examinations of Meat Loaf and Steinman because he manages to shape a clear and simple narrative around the two men: the poor outsider versus the rich kid; the story of a gargantuan performer struggling to find independence from his puppet master; the struggle of two outsized egos over a commercial property bigger than almost any artist could imagine. Recognition of Meat Loaf’s creative input has often been neglected, but Wall goes some way to redeem that, showing that Meat Loaf was also an independent and creative force. In the end, this is a sympathetic yet also critical account of what the two men achieved, and failed to achieve, between them.

The Albums