[Read More]

[Read More]

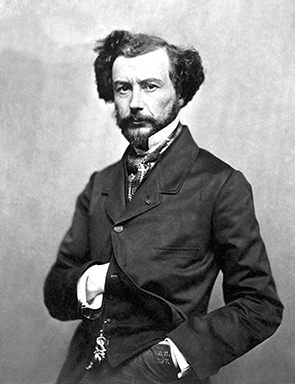

I first met Gustave Flaubert while visiting Carthage in North Africa. There hasn’t been a lot to see at Carthage since the Romans razed it in 146 BC, but it has a romantic appeal for lovers of ancient history. It turned out the notorious novelist shared my enthusiasm, and in fact was researching a historical novel, Salammbô. Despite the desolation, he was glad at last to be on the spot.

“I have indigestion from book reading,” he laughed.

Flaubert was a big man, with large, protruding eyes, full cheeks, a rough moustache, and a red-splotched complexion. That night we spoke after dinner, our tents being pitched not too far from each other. He did not want to talk about his current project, and instead spoke about something else entirely.

Apparently he had long harboured an ambition to write a Dictionary of Accepted Opinions, which would be a list of cliches, “the historical glorification of everything generally approved.” It would cover all possible subjects, he added, and include “everything one should say if one is to be considered a decent and likeable member of society.”

This was unexpected.

“What a grotesque idea,” I said; my comment seemed to make him happy.

“For me the tragic grotesque holds immense charm,” he responded with some eagerness, “it corresponds to the intimate needs of my nature, which is buffoonishly bitter. It doesn’t make me laugh, but sets me dreaming.” He looked out at the dry landscape and stretched his arms. “Almost all human beings are endowed with the gift of exasperating me, and I breathe freely only in the desert.”

Of course I had read Flaubert’s first published book, Madame Bovary, when it appeared as a series in the Revue de Paris two years before. The book, about the perils of dreaming, was an enormous success, and had been put on trial for obscenity. Flaubert told me that, after quoting some passages from the text, the prosecutor had asked the judges: “Gentlemen, do you know of language anywhere in the world more expressive?”

He snorted with laughter. “And this,” he said, tugging my sleeve. “He said, ‘The author does not endeavour to follow such or such a system of philosophy, true or false. He endeavours to produce certain pictures, and you shall see what kind of pictures!’”

“What pictures indeed,” I murmured, recalling scenes of amputation, folly, and, in a description of a tryst combined with an agricultural fair, the most moving piece of prose I have ever experienced. Rarely has one book made its author’s reputation so suddenly.

Flaubert seemed to appreciate my observation.

“You do not have a system of philosophy?” I asked.

He shuddered. “It’s easy, with the help of conventional jargon, and two or three ideas acceptable as common coin, to pass as a socialist humanitarian writer, a renovator, a harbinger of the evangelical future dreamed of by the poor and the mad. Now every piece of writing must have its moral significance, must teach its lesson, elementary or advanced; a sonnet must be endowed with philosophical implications, a play must rap the knuckles of royalty, and a water colour contribute to moral progress. Everywhere there is pettifoggery, the craze for spouting and orating: the muse becomes a mere pedestal for a thousand unholy desires.”

The next day he was on his horse by dawn, but later on I came across him a few kilometres from our campsite. He was sketching some sort of map, and I sat next to him and began to smoke.

“I love history, madly,” he announced. “The dead are more to my taste than the living.”

He looked at me fiercely, as if expecting a response. I confess to being overwhelmed by Flaubert’s presence, completely inadequate. If we had not been alone in the middle of the wilderness, I would have avoided him. As it was, I murmured something about the problems of the times.

“I feel waves of hatred for the stupidity of my age,” he cried with sudden fury. “They choke me. Shit keeps coming into my mouth, as from a strangulated hernia. I want to make a paste of it and daub it over the nineteenth century.” Pause. “We are dancing not on a volcano, but on the rotten seat of a latrine. Before very long, society is going to drown in nineteen centuries of shit.”

“I blame it on the steam engine,” I suggested, trying to move the conversation on from the scatological.

“Speaking of industry,” he cried, changing subject with the speed I realised must be part of his nature, “have you sometimes thought of the quantity of stupid professions it begets, and the vast amount of stupidity that must inevitably accrue from them over the years? What can be expected of a population like that of Manchester, which spends its life making pins? And the manufacture of a pin involves five or six different specialities! As work is broken down into compartments, men-machines take their places besides the machines themselves. Yes, mankind is becoming increasingly brutish.”

*

When I met Flaubert he was 37, having been born in Rouen in 1821. His father was a famous surgeon; on leaving school, Flaubert junior was sent to Paris to study law. He hated it, and failed the first year exams. Early in the second year he had his first attack of epilepsy.

“Each attack was like a haemorrhage of the nervous system, a snatching of the soul from the body,” he told me.

The cure for this was rest and maternal care – and no more law. Two years later his father died, and he had lived with his mother ever since, in Rouen and now Croisset. She did not like him travelling, although he visited Paris several times a year.

When he was 25 he met the poet Louise Colet, who became his mistress. She was 11 years his senior. He told me he would never marry. “There are few people who do not become bourgeois at 30,” he explained. “Paternity would have relegated me to the ordinary condition of life. My innocence in relation to the world would have been destroyed, and that would have cast me into the pit of common miseries. If you participate in life, you don’t see it clearly: you suffer from it too much or enjoy it too much. The less you feel a thing, the more capable you are of expressing it as it is.”

[Read More]

[Read More]

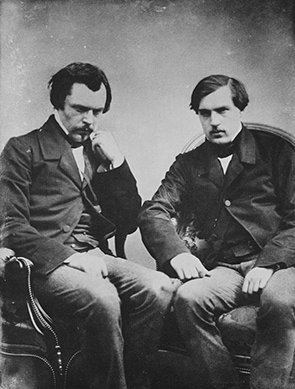

Flaubert had two good friends in his youth, Maxime DuCamp and Louis Bouilhet. When he was 28 he read them a vast philosophical work he had written, La Tentation de Saint Antoine. When I was next in Paris I visited DuCamp and asked him about this.

“The hours that Bouilhet and I spent listening to Flaubert chant his lines—we sitting there silent, occasionally exchanging a glance—remain very painful in my memory,” he said. “We kept straining our ears, always hoping that the action would begin, and always disappointed, for the situation remains the same from beginning to end. St. Anthony, bewildered, a little simple, really quite a blockhead if I dare say so, sees the various forms of temptation pass before him and responds with nothing but exclamations: ‘Ah! Ah! Oh! Oh! Mon dieu! Mon dieu!’ Flaubert grew heated as he read, and we tried to grow warm with him, but remained frozen. After the last reading—it was almost midnight—Flaubert pounded the table: ‘Now: tell me frankly what you think.’”

DuCamp shook his head sadly. “Bouilhet is a shy man, but no one is firmer than he once he decides to express his opinion, and he said: ‘We think you should throw it into the fire and never speak of it again.’” He grimaced. "Mme Flaubert long held our frankness against us. She thought we were jealous of her son.”

Flaubert spent the next five years writing Madame Bovary, and then submitted it to DuCamp , who told him it was “a muddled work to which the style alone does not give sufficient interest. You have buried your novel under a heap of details which are well done but superfluous.” He urged his old friend to allow him to hand the manuscript over to a good editor. Flaubert refused and DuCamp relented, agreeing to publish the novel as it was, except for the scene describing Emma's erotic cab ride through the streets of Rouen. As the serialisation progressed, the government censor asked the department of justice to prosecute the author and the magazine for “outrage of public morals and religion”, and a number of other passages were cut without Flaubert’s permission.

His reputation was made.

*

The next morning I rose early and found the great man shaving before a small mirror.

“I have deteriorated shockingly,” were his words of greeting. “There are mornings when I am afraid of myself, I am so wrinkled and worn. Ah! There were only two or three years in my life—approximately from seventeen to nineteen—when I was entire. I was splendid.”

I shaved silently and Flaubert asked if I was missing my fiancee, of whom I had spoken last night. I told him I was.

“As far as literature is concerned, women are capable only of a certain delicacy and sensitivity,” he told me kindly, and with no relevance that I could see, except to himself and his obsessions. “Everything that is truly sublime, truly great, escapes them. Our indulgence toward them is one of the reasons for the moral abasement that is prostrating us. Never pay any attention to what they say about a book. For them, temperament is everything—the occasion, the place, the author . As for knowing whether a detail (exquisite or sublime in itself) strikes a false note in relation to the whole—no! A thousand times no!”

“Well, Isabelle is not—”

“That may sound cynical to you—”

“It does.”

“—but human nature is not my invention.”

“Surely Louise Colet—”

[Read More]

[Read More]

“Women who have loved a great deal do not know love,” he told me passionately, perhaps remembering one of Colet’s novels in which he had appeared, not to best advantage. “They have been too immersed in it; they do not have a disinterested appetite for the Beautiful. For them, love must always be linked with something, with a goal, a practical concern. They write to ease their hearts—not because they are attracted by Art, which is a self-sufficient principle, no more needful of support than a star.”

He left the next day, inviting me to call on him should I ever be in the neighbourhood of Croisset.

When I reached Paris some months after this I called on Louise Colet. She was bitter – their affair had ended - and said she would not talk of him. Then she opened a drawer and took out a diary, and read aloud.

“1852. His seizure at the hotel. My terror. He begs me not to call anyone. He foams at the mouth: my arm is bruised by his clenched hands and nails. In about ten minutes he comes to himself. Vomiting. I assure him the attack lasted only a few seconds, and that there was no foaming.”

She put down the diary and indicated the interview was at an end. As I was leaving she told me DuCamp had said to her that Flaubert was a “being apart, perhaps a non-being”.

The next day I met Edmond de Goncourt, literary man about town, who told me the hermit of Croisset had a kindly face but, “Though perfectly frank by nature, he is never wholly sincere in what he says he feels or suffers or loves.”

This, it seemed to me then, was outrageous.

I wrote to Flaubert, asking for an interview to be published in an obscure magazine called Reading Project – a publication in, of all places, the English colony of New South Wales. It was – and still is - a beacon of good taste and insight, although not well known in the metropolitan centres. But a copy I’d sent met with his approval.

So he invited me to his home. Of his work on the Carthage novel he wrote: “I’ve finally achieved the erection, Monsieur, by dint of self-flagellation and masturbation. Let’s hope there’s joy to come.”

Taking this curious description of literary production as good news, I went to stay with some friends near Saumer, and then made my way into Normandy and Croisset.

Flaubert lived in a long white house on the banks of the Seine. When I arrived and opened the iron gate, the yellow leaves were falling on the river. I walked up the path, and as I waited by the door, looking towards the river, a steamer passed. Flaubert’s mother greeted me, and I was shown into a large study with five windows, in which comfortable green armchairs faced a good fire. The novelist, wearing a silk skullcap, was pacing up and down. He greeted me restlessly, pointing to the library around him: “Me and my books, in the same apartment: like a gherkin in its vinegar!”

We talked a bit, and it emerged that he had read a newspaper that morning, for the first time in a while, and this had depressed him. There had been news of some literary prize or other.

“Have you ever remarked how all authority is stupid concerning Art?” he told me. “Our wonderful governments (kings or republics) imagine that they have only to order work to be done, and it will be forthcoming. They set up prizes, encouragements, academies, and they forget only one thing, one little thing without which nothing can live: the atmosphere.”

And so to the questions.

“What are the three best things in the world?”

“The three finest things that God ever made are the sea, Hamlet, and Mozart’s Don Giovanni.”

“What is good art?”

“The finest works are those that contain the least matter. What mind worthy of the name [of artist], starting with Homer, ever reached a conclusion?” Pause. “What seems to me the highest and most difficult achievement of Art is not to make us laugh or cry, nor to arouse our lust or rage, but to do what nature does—that is, to set us dreaming.”

I was used to Flaubert’s pauses by now—often they indicated the preparation of a thought that would qualify or even contradict the one that had gone just before.

“Is good art beautiful?”

“It is so easy to chatter about the Beautiful. But it takes more genius to say, in proper style: ‘Close the door,’ or ‘He wanted to sleep’. Pause. “The time for beauty is over. Mankind may return to it, but has no use for it at present. The more Art develops, the more scientific it will be, just as science will become artistic. Separated in their early stages, the two will become one again when both reach their culmination.”

Sometimes, I thought, his views of reality were so wild it was fortunate he was a great novelist.

[Read More]

I asked a question inspired by the Romantic proclivities of the first part of our century.

“Should a writer be his own subject?”

“There are writers whose slightest cry is melodic, whose every tear wrings the heart, and who have only to speak of themselves to remain eternal. Byron belongs to this class. Yet Art must rise above personal affections and neurotic susceptibilities! The artist in his work must be like God in his creation,” Flaubert exclaimed, “invisible and all-powerful. He must be everywhere felt, but never seen. It is time to banish anything of that sort from it, and give it the precision of the physical sciences." Pause. “Homer, Rabelais, Michelangelo, Shakespeare and Goethe seem to me pitiless. They are unfathomable, infinite, manifold. Through small apertures we glimpse abysses whose sombre depths turn us faint. And yet over the whole there hovers an extraordinary tenderness.” Pause. “I think the greatest characteristic of genius is power. Hence, what I detest most of all in the arts, what sets me on edge, is the ingenious, the clever.

“Shakespeare frightens me the more I think of him. In their entirety, I find his works stupendous, exalting, like the idea of the planetary system. The greatest, the rare true masters, are microcosms of mankind: not concerned with themselves or their own passions, discarding their own personality, they are, instead, absorbed in that of others; they reproduce the Universe, which is reflected in their works, scintillating, varied, manifold, like an entire sky mirrored in the sea with all its stars and all its azure. When I have reached the crest of one of his works I feel that I am high on a mountain: everything disappears, everything appears. I am no longer a man, I am an eye.”

“Who is your ideal reader?”

“One must write for oneself, first and foremost. Only that way does one stand a chance of producing something good.”

“Do you enjoy writing?”

“Sometimes, when I am empty, when words don’t come, when I find I haven’t written a single sentence after scribbling whole pages, I collapse on my couch and lie there dazed, bogged in a swamp of despair, hating myself and blaming myself for this demented pride that makes me pant after a chimera. A quarter of an hour later, everything has changed; my heart is pounding with joy. Last Wednesday I had to get up and fetch my handkerchief; tears were streaming down my face. I had been moved by my own writing: the emotion I had conceived, the phrase that rendered it, and the satisfaction of having found the phrase—all were causing me the most exquisite pleasure.” Pause. “Few men, I think, will have suffered as much as I for literature.”

Food arrived and we ate, in my case with great hunger. Flaubert paused, with a forkful of meat halfway to his mouth. “Prose was born yesterday, you have to keep that in mind. Verse is the form par excellence of ancient literatures. All possible poetic variations have been discovered; but that is far from being the case with prose.”

“How close did you become to Emma?”

I was thinking of Baudelaire’s comment, published somewhere, that “Madame Bovary, in the most energetic and ambitious aspects of her character, and also in her strong predilection for reverie, remained a man.”

“The characters I create drive me insane,” he said now, “they haunt me; or rather, I haunt them: I live in their skin. When I was writing about Madame Bovary taking poison, I had such a distinct taste of arsenic in my mouth that I had two attacks of indigestion, one after the other—I vomited my entire dinner.”

“Could you imagine any other life for yourself?”

“The thing is to keep fucking, keep fucking: who cares what child the muse will give birth to? Isn’t the purest pleasure in her embraces?”

An obvious note on which to end. But, I think, the right one.

Salammbô is set during the Mercenary Revolt of 241–237 BCE. The Carthaginians had just settled terms with Roman during the First Punic War, but Carthage had relied upon mercenaries. Without adequate funds, Carthage was unable to pay its mercenaries and Flaubert’s book dramatizes the conflict between Carthage and its mercenary forces who demand to be paid.

When the mercenaries interrupt a feast, Salammbô, a priestess and daughter of Hamilcar Barca, the Carthaginians foremost general, intervenes and demands the mercenaries remain peaceful. In the course of events, a mercenary leader, Matho, mistakenly believes Salammbô has made an offer of intimacy when she hands him a drink. The mercenaries are persuaded to leave the city, but on a rumour that Carthage does not have the money to pay them, and that some of their forces that have stayed behind have been slaughtered, they march back to the city. During the attack, Matho steals a sacred veil from the temple, and Salammbô feels compelled to enter the mercenaries’ camp to retrieve it. Matho and Salammbô have sex, and Salammbô is suspected of being a traitor. With the return of Hamilcar Barca the mercenaries are finally defeated and Matho is executed. Salammbô dies of shock.

The copyright for Salammbô has expired so the book is available for free.

Follow this link to download your free copy in an ENGLISH TRANSLATION.

The city of Carthage succumbed to a three year Roman siege in 146 BCE. It was the culmination of a long period of conflict known as the Punic Wars between Roman and Carthage.

The First Punic War began in 264 BC and lasted 23 years. It was a contest between the two powers over influence in the Mediterranean Sea which ended with a treaty that ceded Sicily to Rome.

The Second Punic War began in 218 BCE and lasted 17 years. The two powers struggles for territory in Italy and in what is now modern Spain. It famously featured Hannibal’s army crossing the Alps with war elephants, although most of them perished. The war ended in Carthage’s defeat after Rome’s invasion of Carthage in 204 BCE and Carthage’s final defeat at the Battle of Zama in 202. Carthage lost its overseas territories and its terms of surrender made it political subservient to Rome.

The Third Punic War saw the destruction of Carthage. It was instigated by Rome because Carthage had technically violated the terms of their treaty made at the end of the Second Punic War. When the city was finally breached civilians were slaughtered or captured and made slaves. The city was destroyed. The image above is a part of the ruins left at Carthage.

Emma Bovary is the bored housewife of a provincial doctor who finds that motherhood cannot even fulfil he emptiness she feels. Influenced by novels and desiring passion, she falls into a love affair with a local landowner, setting in motion a chain of events which will lead to her ruin.

The scene alluded to by Michael Duffy – “a description of a tryst combined with an agricultural fair, the most moving piece of prose I have ever experienced” appears in the eighth chapter of the second part of the novel, in which Rodolphe’s attempts to seduce Emma Bovary are interspersed with the announcements made by the fair president about produce and prizes, making for a somewhat comical love scene. An extract from the scene follows:

Rodolphe with Madame Bovary was talking dreams, presentiments, magnetism. Going back to the cradle of society, the orator painted those fierce times when men lived on acorns in the heart of woods. Then they had left off the skins of beasts, had put on cloth, tilled the soil, planted the vine. Was this a good, and in this discovery was there not more of injury than of gain? Monsieur Derozerays set himself this problem. From magnetism little by little Rodolphe had come to affinities, and while the president was citing Cincinnatus and his plough, Diocletian, planting his cabbages, and the Emperors of China inaugurating the year by the sowing of seed, the young man was explaining to the young woman that these irresistible attractions find their cause in some previous state of existence.

“Thus we,” he said, “why did we come to know one another? What chance willed it? It was because across the infinite, like two streams that flow but to unite; our special bents of mind had driven us towards each other.”

And he seized her hand; she did not withdraw it.

“For good farming generally!” cried the president.

“Just now, for example, when I went to your house.”

“To Monsieur Bizat of Quincampoix.”

“Did I know I should accompany you?”

“Seventy francs.”

“A hundred times I wished to go; and I followed you—I remained.”

“Manures!”

“And I shall remain to-night, to-morrow, all other days, all my life!”

“To Monsieur Caron of Argueil, a gold medal!”

“For I have never in the society of any other person found so complete a charm.”

“To Monsieur Bain of Givry-Saint-Martin.”

“And I shall carry away with me the remembrance of you.”

“For a merino ram!”

“But you will forget me; I shall pass away like a shadow.”

“To Monsieur Belot of Notre-Dame.”

“Oh, no! I shall be something in your thought, in your life, shall I not?”

“Porcine race; prizes—equal, to Messrs. Leherisse and Cullembourg, sixty francs!”

Rodolphe was pressing her hand, and he felt it all warm and quivering like a captive dove that wants to fly away; but, whether she was trying to take it away or whether she was answering his pressure; she made a movement with her fingers. He exclaimed—

“Oh, I thank you! You do not repulse me! You are good! You understand that I am yours! Let me look at you; let me contemplate you!”

A gust of wind that blew in at the window ruffled the cloth on the table, and in the square below all the great caps of the peasant women were uplifted by it like the wings of white butterflies fluttering.

“Use of oil-cakes,” continued the president. He was hurrying on: “Flemish manure-flax-growing-drainage-long leases-domestic service.”

Rodolphe was no longer speaking. They looked at one another. A supreme desire made their dry lips tremble, and wearily, without an effort, their fingers intertwined.

Madame Bovary, Part Two, Chapter 8 (Translated from the French by Eleanor Marx-Aveling)

The copyright for Madame Bovary has expired so the book is available for free from the Gutenberg Project.

Follow this link to download your free copy in an ENGLISH TRANSLATION.

Follow this link to download your free copy in the original FRENCH.

Louise Colet was a French writer who had a long-term affair with Flaubert. She was married to Hippolyte Colet, and she entertained the literary community, which is how she met Flaubert. Their relationship lasted eight years, and when Flaubert eventually broke with her, she wrote a novel, Liu, which included a thinly disguised account of the relationship. Prior to their estrangement in 1855, Flaubert also conducted a long-term correspondence with Colet, in which he described his progress writing Madame Bovary.

Gustave Flaubert was born on December 12, 1821, in the hospital of Rouen. His father, Achille-Cléophas, was its chief surgeon in the hospital of Rouen where Flaubert was born in 1821. He was a great admirer of Napoleon during his reign and distanced himself from Catholicism.

While working at Rouen Achille-Cléophas met Caroliine Flueriot and they married when Caroline was 18 years old. They had six children, but only Flaubert, his older brother Achille, and his younger sister, Caroline, survived childhood.

At Rouen Achille-Cléophas took care of the sick and managed the medical school. He died in 1846.

Maxime Du Camp, like Flaubert, was the son of a successful surgeon. He travelled in Europe with Flaubert between 1849 and 1851, and each wrote about their experiences of travelling with each other.

Madame Bovary was first published in a serialised form in the Revue de Paris, a magazine established by Du Camp.

Du Camp was also an early amateur photographer. He used this interest to publish some of the first travel books to include photographic plates.

Louis Bouilhet went to school with Flaubert. He was a poet and a dramatist. He dedicated his first poem, ‘Melaenis, conte romain’ to Flaubert. The subject of the poem was Roman manners during the reign of Emperor Commodus (who is portrayed by Joaquin Phoenix in Ridley Scott’s 2000 film, Gladiator). He also had success in the theatre and his plays were well-received by critics.

Flaubert regarded Bouilhet as his literary advisor, and always sought his advice on anything he wrote. Flaubert reputedly referred to Bouilhet as ‘Monseigneur’ as a sign of the deference he paid Bouilhet.

La Tentation de Saint Antoine (The Temptation of St Anthony) is a dramatic poem in prose which was first inspired by the above painting. At the time it was thought to be by Pieter Bruegel, but is now thought to be by one of his followers.

Click here to open another tab in which you can view the painting, hosted by Wikipedia, in close detail.

The painting depicts the temptation of St Anthony. St Anthony is portrayed in the painting’s foreground resisting the temptations of the devil, while he is later portrayed being carried into the air by demons.

Flaubert wrote an adaptation of the story in the form of a playscript which dramatizes one night in the life of St Anthony. He began working on it in 1845 and it wasn’t completed until 1874.

La Tentation de Saint Antoine (The Temptation of St Anthony) is a dramatic poem in prose which was first inspired by the above painting. At the time it was thought to be by Pieter Bruegel, but is now thought to be by one of his followers.

Click here to open another tab in which you can view the painting, hosted by Wikipedia, in close detail.

The painting depicts the temptation of St Anthony. St Anthony is portrayed in the painting’s foreground resisting the temptations of the devil, while he is later portrayed being carried into the air by demons.

Flaubert wrote an adaptation of the story in the form of a playscript which dramatizes one night in the life of St Anthony. He began working on it in 1845 and it wasn’t completed until 1874.

Edmond and Jules de Goncourt

Edmond de Goncourt and his brother Jules came from a family of minor aristocrats. Edmond collaborated with his brother in art criticism, a journal and several novels.

After the death of Jules in 1870 Edmond continued to write novels on his own, but became embittered at the success of other French writers. He bequeathed his entire estate for the foundation and maintenance of the Académie Goncourt, France’s premier literary award which has been awarded since 1903 for ‘the best imaginary prose work of the year.’

It is a little known fact that the Reading Project began with bikerbuddy’s great great great grandfather swifterwalkerbuddy, silent partner in the invention of the first bicycle by Karl von Drais in Germany, 1817.

By the time Flaubert was writing Madame Bovary, swifterwalkerbuddy had had another great idea which he was destined to go to his grave believing he had solely invented: the book review. Due to a profligate life he had nothing to leave as a legacy to his family except his desire to endlessly write reviews; a charming habit which has been maintained by his most wastrel of descendants until this day.

Flaubert, who knew swifterwalkerbuddy by reputation only, wrote in a letter to Louis Bouilhet, “If only that swifterwalkerbuddy would review my new novel, my career might finally get a pedal on.”

This account is entirely disputed by scholars.

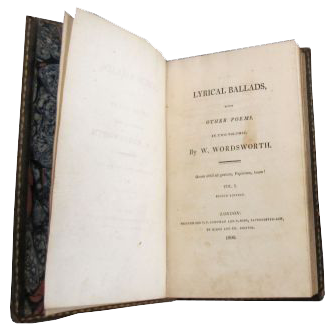

Lyrical Ballads

William Wordsworth wrote in the Preface to the Lyrical Ballads, “. . . all good poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings . . .” The Preface to the Lyrical Ballads not only introduced the poems in the slender volume first published by Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1798, but became a manifesto for Romantic thought, the intellectual and cultural phenomenon inspired by Enlightenment writers and the events of the French Revolution.

The emphasis in Romantic writing was subjective individual experience, an expression of feeling and a heightening of that feeling through the contemplation of nature or other art, objects or events which allowed the poet to reflect in a meditative state. The following is an extract from the Preface that expresses some of Wordsworth’s ideals of what a Romantic poet sought to be:

What is a poet? To whom does he address himself? And what language is to be expected from him? He is a man speaking to men: a man, it is true, endued with more lively sensibility, more enthusiasm and tenderness, who has a greater knowledge of human nature, and a more comprehensive soul, than are supposed to be common among mankind; a man pleased with his own passions and volitions, and who rejoices more than other men in the spirit of life that is in him; delighting to contemplate similar volitions and passions as manifested in the going-on of the universe, and habitually impelled to create them where he does not find them. To these qualities he has added a disposition to be affected more than other men by absent things as if they were present; an ability of conjuring up in himself passions, which are indeed far from being the same as those produced by real events, yet (especially in those parts of the general sympathy which are pleasing and delightful) do more nearly resemble the passions produced by real events, than any thing which, from the motions of their own minds merely, other men are accustomed to feel in themselves; whence, and from practice, he has acquired a greater readiness and power in expressing what he thinks and feels, and especially those thoughts and feelings which, by his own choice, or from the structure of his own minds, arise in him without immediate external excitement.