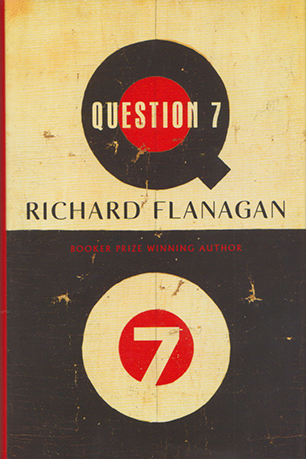

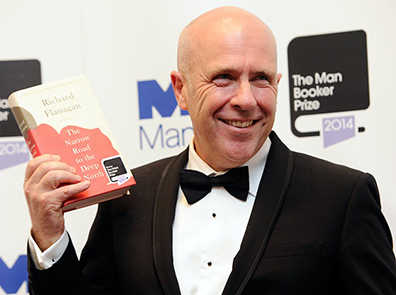

When he was only twenty one Richard Flanagan almost died in a kayaking accident on the Franklin River, Tasmania. It’s an incident he describes in horrific detail in the closing section of his latest book, Question 7. Flanagan was eventually rescued and helicoptered out, and the river rapid which almost ended his life was later named in his honour. The experience inspired Flanagan’s first novel, Death of a River Guide, in which he attempted, through his fiction, to confront the moment when he faced death. Paradoxically, Flanagan tells us, he has kayaked the same stretch of water, “seventy or eighty times since”, facing the nightmare that he relived, over and over, as a present psychological reality that has shaped his life.

The incident is mentioned in Question 7 a few times prior to this final section, but other than that it is the part of the book that feels least integrated on a first reading. Nevertheless, even as you first read it, it is gripping, and intuitively it feels like a fitting coda to this remarkable book. Reflecting upon it and understanding its significance is also about understanding the whole point of Richard Flanagan’s history-cum-memoir-cum-autofiction: that history, culture and our relationships are like the river, vast forces beyond our control, and that facts and a traditional Western conception of history are limited when attempting to express a full understanding of our lived lives and what they mean. Flanagan’s book initially reads like a memoir or family history. It begins with an account of his father’s experience in the Japanese Ohama Camp for prisoners of war where Australians were used as slave labour in the Ohama coal mine. But Flanagan soon immerses his reader in the story of one of the most significant moments in world history – the dropping of the bomb on Hiroshima on the 6 August 1945. From this momentous event, Flanagan draws us back to the personal: had the bomb never been dropped, killing 60,000 or 80,000 or 140,000 (Flanagan’s point is that no one knows the true death toll and the true human cost can never be a mere calculation), his father, could not have survived another winter as a prisoner of war. Without the bomb, Flanagan never would have existed.

It’s a central precept of this book: that the consequences of any event or action can never be calculated, and certainly they cannot be known in advance; that the idea of explaining history lies not only within academic historical paradigms, but that we might also understand our lives as being, “born out of the deaths of others” and that, “life is breathed into us from stories we invent out of songs, collages of jokes and riddles and other fragments”. It’s an idea that might easily be overlooked amongst the more colourful aspects of Flanagan’s narrative.

On the subject of history, Flanagan received a scholarship to study it at Oxford University when he was young and soon realised that European culture did not mesh with his own understanding and lived experience of the world:

Many years later, when I went to Oxford, I studied history, an idea of time formed over 3000 years of human experience in Europe, which, I discovered, made perfect sense of European time, stopping at all stations of European progress and European thought. It was a straight railway line that perfectly mirrored an experience that became an idea, and an idea that became experience, and an experience that became European thought and then the European novel.

But it made no sense of Tasmania.

Question 7 is a bravura performance which demonstrates the very thesis that Flanagan advances. Understanding our lives and our world cannot be achieved by a linear rail line of significant events, nor can Flanagan tell his own story within the ideological constructs of a culture alien to his own, which sought to dominate, exploit and destroy it. Flanagan is a Tasmanian. Many would assume he is a white writer, but his family history reveals aboriginal ancestors as well as the ‘stain’ of a convict heritage which was formerly unacknowledged. In this, Flanagan’s narrative has echoes and rhythms. We remember the enslavement of Australian prisoners in Japan. Flanagan introduces a corresponding fact in the enslaved working conditions of convicts. Some of Flanagan’s descendants were therefore either institutional slaves or were the subject of a concerted effort at genocide.

I think the point of the railway metaphor is the implication about European history: that there is an implied inevitability in European progress and dominance which justifies its history. If not as much these days when traditional history is being deconstructed, then certainly during the period Flanagan attended Oxford when the colonial stain, racial differences or being a woman were enough to discredit any would-be scholar. Written in this way, the dispossession of Aborigines of their land, the introduction of deadly diseases and the results of violent conflict are inscribed within a broader European narrative framed by race, religion and a sense of inevitable progress. This is what Flanagan writes against.

As I read Question 7 I was struck by Flanagan’s refrain ‘That’s life’. It’s a grim acceptance of the realities of life, whether it be the insight that suffering affords us, or life’s perceived unfairness. When Flanagan is confronted by a woman who believes he has stolen her idea for a novel based upon the death of her friend in the Franklin River – “demanding I tell her how I knew the exact details” – Flanagan reflects, “That’s life”. Unfortunately the suffering of the woman’s friend is not unique nor the story uniquely her own. The refrain reminded me of Kurt Vonnegut’s in Slaughterhouse Five – “So it goes” – a flippant riposte against death which reflects a deeper understanding, that the universe cares little for our individual lives: that we make of our lives what we can. This thought as I read preceded Vonnegut briefly entering Flanagan’s story: how an idea suggested to Bernard Vonnegut by H.G. Wells became the catalyst for Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle.

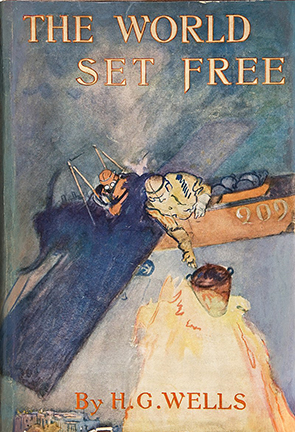

The novel is peppered with little ‘chain reactions’ like this: of one seemingly insignificant moment begetting something unforeseen and consequential. The first chain reaction is not the bomb, nor is it the last. Flanagan’s refrain and Vonnegut’s intrusion are just a small example of Flanagan’s purpose and method. One might try to explain it by saying that everything is connected, although that reduces the complexity and richness of Flanagan’s text. But that is the sense of reading this book. Flanagan’s story is not linear because it is an attempt to understand Flanagan’s own life and his family, but also the meta-narratives that shape culture and history: the unexpected genesis of our own world. To this end Flanagan is interested in literature and personal stories, family tales, memories, the historical record and the deep intersection between seemingly disparate people, experiences and events. Just as he argues his own existence was impossible without the bomb, the life and work of H.G. Wells, and Wells’s affair with writer Rebecca West, become consequential in Flanagan’s own life narrative. And these seemingly disparate elements are woven into a grand narrative that attempts to make sense of European history and its impact on Tasmania, as well as Flanagan’s own family. Wells’s most famous story, The War of the Worlds, expresses both the destructive power of the bomb as well as the invasive destruction of Tasmania and the subjugation of its people.

The title of the book is taken from a short story by Anton Chekhov which parodied arithmetic questions asked of school children. Question 7 in Chekhov’s story introduces us to the idea of the implacable train:

. . . a train had to leave station A at 3 a.m. in order to reach station B at 11 p.m.; just as the train was about to depart, however, an order came that the train had to reach station B by 7 p.m. Who loves longer, a man or a woman?

The disconnect between the salient facts and the actual question epitomises the problem of history in the service of understanding. Flanagan indulges us with his own parody of Chekhov’s parody:

If Thomas Ferebee releases a lever at 8:15 am, says, ‘Bomb away!’, and a bomb falls six miles before exploding, how many people need to die in order that you might read this book?

Of course, the number, itself, is the disputed fact: 60,000 or 80,000 or 140,000 people are not really the point of the question. But the disconnect is not with logic, but between two cultural narratives. The destruction of Hiroshima by the bomb or the attempted destruction of the Tasmanian people by policy and practice are merely two examples of an historical ur-story. One is understood, the other has mostly been a sidenote. Flanagan intends to change that. And he would not be the first to try something like it. Before Vonnegut wrote Slaughterhouse Five, the bombing of Dresden was something of a sidenote, too. But how many sidenotes are there? Flanagan lists the bombing of France by the allies which killed around 57,000 French civilians. Or the bombing of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia during the Vietnam War which totalled more than double the entire number of bombs dropped in the Second World War, making it the largest aerial bombardment in history.

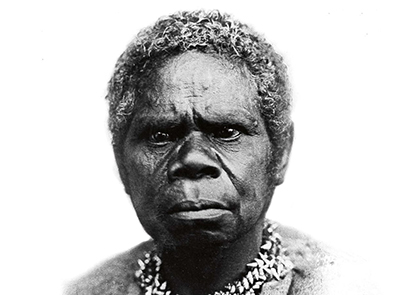

Alongside these atrocious events is the near genocide of the Tasmanian aborigines. Mass slaughters are endemic to history. But like those other events, the Tasmanian story does not end at one point: did not end with Truganini. This is Flanagan’s point: that their supposed extinction is a myth of European history. That set against its colonial and European influences, many Tasmanians have maintained an identity defined separate from the received tenets of European history. But the last irony, that the conquerors may in turn be changed or ‘indigenised’, is one not anticipated by colonialism: that “white people had begun in some ways to think like black people.” In this sense, history is not written, not a monument, but lived and relived and is in constant flux and change. It’s an insight that explains the relevance of a reference Flanagan makes to the idea of a ‘fourth tense’ in his Acknowledgements (again ‘connecting’, again reminding of us of Wells and his Time Traveller and the fourth dimension): that history is not just a past, but experiences which shape our pasts, present and futures. That experience is something we live with as much as we might try to put it from our minds: like almost drowning in the Franklin.

No one need die for you to read this book. But the deaths of many have contributed to the shaping of this personal story. Question 7 is so good you should simply want to read it. That’s life!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter